Plant-feeding insects stand out from all other organisms on the planet in two ways. First, they are unusually diverse: one out of every four species is an herbivorous insect. Second, most insect species specialize on particular types of plants to the exclusion of all other plants in their habitat.

One explanation for the pronounced diversity and specialization in herbivorous insects is that adaptation to new host plants frequently drives the formation of new species. To test this hypothesis, we must establish a direct link between traits that contribute to host adaptation and traits that prevent successful reproduction between species.

To investigate the link between host adaptation and speciation, we focused on a pair of closely related pine sawfly species (common pests of pine trees in North America) that differ in the pine species that they attack. While Neodiprion pinetum (the white pine sawfly) only attacks white pine, Neodiprion lecontei (the redheaded pine sawfly) attacks several other pine species, but generally avoids white pine.

We know that these two species can—and occasionally do—mate with one another. We have found them at the same collecting sites at the same time, and we have even collected hybrid larvae in the field. We have also crossed them in the lab and produced viable, fertile hybrid offspring. However, despite occasional hybridization, these species remain genetically, behaviorally, and morphologically distinct in the wild.

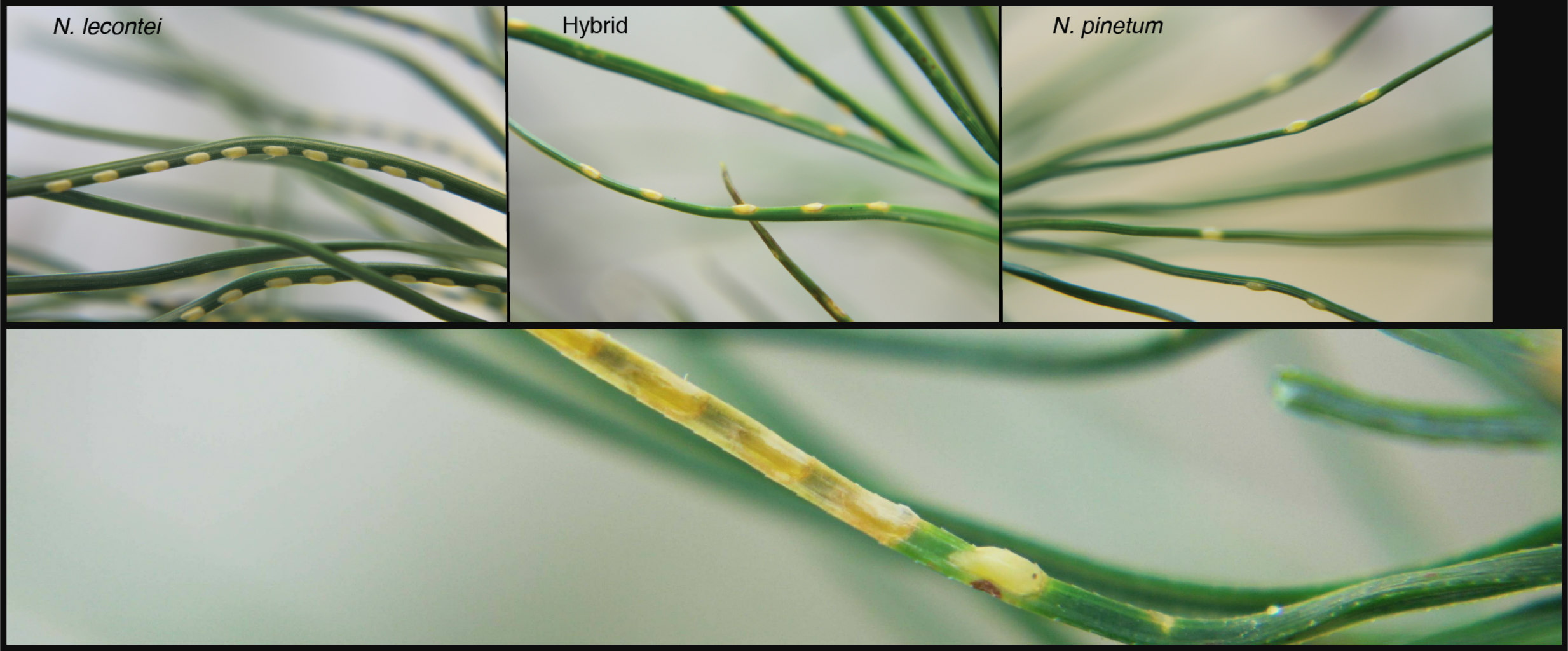

Together, our observations tell us that something is preventing N. pinetum and N. lecontei from merging into a single species. Some of our early crosses between these species in the lab hinted at one possible explanation. We noticed that when hybrid females laid their eggs on pines other than white pine, they hatched just fine. However, when hybrid females laid their eggs on white pine, the needles dried out and the eggs failed to hatch. In other words, something about the egg-laying behaviors of hybrid females was “off”.

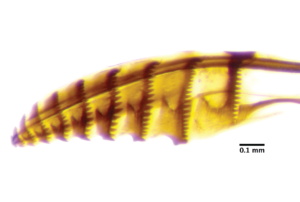

To lay their eggs, Neodiprion females carve individual egg-bearing pockets into the host needle, using a saw-like structure (ovipositor). In doing so, they face two challenges: circumventing the resins that protect the pine needles (which can drown eggs) and avoiding needle desiccation (which can also kill the eggs). Notably, the needles of white pine are considerably thinner and less resinous than those of the hosts typically preferred by N. lecontei females. We therefore predicted that N. pinetum females should have traits that minimize desiccation risk (e.g., fewer or smaller needle cuts), while N. lecontei females should have traits that circumvent host resins (e.g., deeper cuts that effectively drain resin).

Consistent with our predictions, we found the N. pinetum females laid fewer eggs per needle than N. lecontei females. N. pinetum females also never cut a resin-draining “preslit” (a non-egg bearing cut) at the base of the needle, while N. lecontei females always did. We also found that N. pinetum females had smaller, straighter “saws” than N. lecontei females, suggesting that these females make shallower needle cuts. Together these traits match our prediction that N. pinetum traits should minimize desiccation risk, while N. lecontei traits are expected to reduce resin flow to eggs (but increase desiccation risk).

But what do these traits look like in the hybrids? We found that hybrid females have a strong preference for white pine (like N. pinetum females), but have larger saws, lay more eggs per needle, and cut more preslits than N. pinetum females. This unfortunate combination of traits leads to needle desiccation and hatching failure, drastically reducing the ability of hybrid females to reproduce successfully. The poor egg-laying performance of hybrid females may explain, in part, how N. lecontei and N. pinetum remain distinct species despite occasional hybridization in the wild.

Our work demonstrates how maladaptive combinations of parental host-use traits can lead to reductions in fitness in hybrid individuals, which in turn limit gene flow between the parental species. This provides direct evidence that host adaptation contributes to the formation of new species. Additionally, our work suggests that adaptations for laying eggs on different hosts may be an especially important (but currently underappreciated) driver of speciation.

Comments