A bat with few friends and a short life

Group size, survival and surprisingly short lifespan in socially foraging bats

While many bat species roost in large flocks, more stable social groups with individuals also foraging together are relatively rare. The South American Pallas’s mastiff bat lives in such groups, with individuals eavesdropping on the echolocation calls of other group members to help locate their insect prey.

A team of researchers at Max Planck Institute of Ornithology, led by Yann Gager, conducted the first detailed investigation of social structure in these bats. They predicted that the bats would live in small groups, because of the difficulty of co-ordinated flight and likelihood of acoustic interference if the bats foraged in big groups. Or, to put it another way, too many bats would just get in each other’s way. This prediction was proven correct: Pallas’s mastiff bats live in small (but stable) groups of 3-13 individuals.

A more surprising finding was the short lifespan of these bats; just 1.8 years on average, over three times less than the average bat lifespan. The researchers suggest this result’s from the Pallas’s mastiff bats highly specialised diet, feeding on ephemeral insect swarms that only appear at dawn and dusk. A life lived on this “energetic edge” seems to be a short one.

Nematodes in the tropics

Nematode worms are a diverse group of more than 20,000 species (including the classic model species C.elegans) and are remarkably abundant; one estimate suggested that 4 out of every 5 multicellular organisms on the planet are nematodes. Yet for all their abundance, we know astonishingly little about their lives in the wild. For example, there are some indications that nematodes are less species-rich in the tropics than in temperate zones, which would be in stark contrast to most other animal groups. However, this might just reflect our ignorance of nematode diversity and abundance in these regions.

Gerhard Zotz and Walter Traunspurger looked to fill these gaps by investigating nematode diversity in the freshwater habitats created by water trapped in the crowns of tank bromeliad plants in Panama. They found 89 species of nematodes, of varying feeding types, with individual plants containing up to 25 different species. Notably, after rotifers, nematodes were the most abundant animals in these micro-habitats. This suggests that nematodes are actually likely to exist in considerable diversity and abundance in the wider tropical ecosystem; we just need to look for them.

A gut feeling that size matters

Vertebrate bacterial gut diversity: size also matters

An increasing body of research suggests that diversity of bacteria in the gut has significant implications for their animal hosts. While many factors seem to affect bacterial diversity within an individual’s gut, a relatively simple one had not previously been studied: size. It is well established that in other habitats greater size generally means greater diversity, so is this also true in the habitat of an animal’s gut?

A team of French researchers at the INRS, led by Jean-Jacques Godon, compared bacterial diversity in the guts of 71 species of birds, reptiles, and mammals (including humans). They found a strong correlation between gut size and diversity, with larger animals generally having a wider range of bacteria present in their guts. Gut volume should therefore be considered along with other parameters when explaining why diversity varies among species.

Boundaries are important for urban rabbits

Importance of latrine communication in European rabbits shifts along a rural-to-urban gradient

For many mammals, communication networks are based around deposition of excreta in latrines. These latrines can be formed at the edge of territorial boundaries, for between-group communication, or around key areas of the home range, for within-group communication.

Which type of latrine communication is more important for European rabbits seems to depend on whether they live in rural or urban areas. Urban rabbits locate latrines in higher proportions at the edge of their territories, in contrast to rural rabbits who locate more latrines around their burrows.

Rural rabbits seem then to prioritise communication within their social groups. For urban rabbits, with their smaller group sizes but higher population densities, between-group communication seems to be more important; when you have so many neighbours crammed around you, ensuring everyone knows their boundaries becomes crucial. This research provided a novel insight into the alterations man-made habitats can make to animal behavior.

Citizen science: through the looking glass

Citizen science through the OPAL lens

Citizen science – the collection of data by members of the public in collaboration with professional scientists – has particular potential for the field of ecology. Ecological studies often require data to be collected from far-flung locations over a period of many years; very difficult for a single – or even multiple – research groups to gather. Utilising the wider public can allow the collection of more expansive data sets, with the added benefit of engaging the public in ecological research.

Of course citizen science comes with many challenges, which were discussed in this collection of articles evaluating the success of the UK’s Open Air Laboratories national citizen science network, now approaching its 10th anniversary. What makes lay-people keen to become involved with research, the quality of the data they gather, and the results arising from these studies were among the topics discussed.

Collection organiser Poppy Fraser Lakeman discussed these issues in more detail on our blog.

A cockroach in disguise

Attaphila cockroaches make a living by sneaking into the nests of leaf-cutter ants. These ants farm a fungus that provides an ideal food source for the invading cockroaches. Research led by Volker Nehring and Patrizia d’Ettorre at the University of Copenhagen investigated how the cockroaches steal food from a heavily guarded ant colony without being detected.

Behavioural experiments suggest that cockroaches are able to disguise themselves with the colony-specific cuticular chemical profile used by the ants to recognise their nest-mates; cockroaches were not attacked by ants from the same colony they live in, but were attacked by ants from other colonies. Chemical analysis confirmed that the cockroaches copy their host colonies specific cuticular chemical profile.

Studying these cockroaches also enables us to learn more about how the ants themselves communicate. Cockroach species with lower concentrations of cuticular chemicals were less likely to be attacked by ants from other colonies. This supports the asymmetric model of ant nest-mate recognition; rather than ‘knowing’ their colonies specific profile, ants just respond to any unfamiliar cues; hence cockroaches with fewer chemical cues are less likely to find their disguise being uncovered.

Hunting as a management tool?

Hunting as a management tool? Cougar-human conflict is positively related to hunting pressure

When large predators roam near human settlements, conflict can become inevitable. A common approach to managing these pressures is to allow human hunters to remove predators near human settlements. The assumption is that this reduces human-predator conflict: an assumption this research challenges.

Analysing a 30 year dataset on hunter-caused cougar mortality in Canada, researchers found a clear pattern of greater cougar trophy-hunting increasing human-cougar conflict. They note that trophy hunters focus on the largest males, yet it is usually smaller, younger males that are more likely to come into conflict with humans. Removing large resident males may also disrupt cougar social structures, dispersing cougars over larger areas and making conflict with humans more likely.

The work adds to a growing body of evidence that hunting provides a poor – and often counter-productive – method for managing conflict with large predators.

Authors Kristine Teichman, Bogdan Cristescu and Chris Darimont discussed their research in more detail on our blog.

Dinosaur distributions

A long-standing – and somewhat perplexing – problem in dinosaur ecology is the apparent high levels of diversity of large-bodied dinosaurs in North America during the Cretaceous period. Unlike modern-day large-bodied vertebrates where a few species, such as wolves and caribou, roam across very large areas, their dinosaur equivalents of 70 million years ago lived in much narrower ranges.

Thomas Cullen and David Evans at the University of Toronto assessed the reasons behind these patterns by studying fossil microsites from the late Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada. Microsites are concentrated assemblages of small bones and teeth, thought to provide a good representation of community composition at the time they were deposited.

The prevailing theory to explain high dinosaur diversity is that these species were particularly sensitive to environmental changes, preventing them from roaming across large areas. The researchers tested this by comparing dinosaur diversity at two environmentally distinct microsites from the same time period. Contrary to this theory, there was no difference in relative abundance of different dinosaur taxa in these differing environments. A different explanation would appear to be required to explain this perplexing historical pattern.

Then and now: tracking the decline of an iconic tree

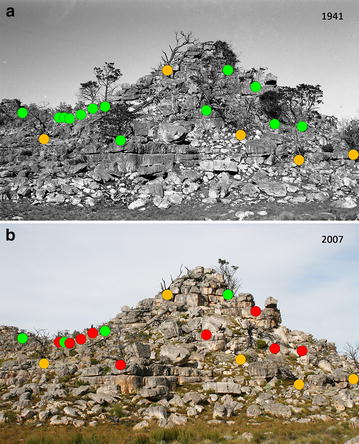

The Clanwilliam cedar is one of South Africa’s most iconic trees. It is also one of its most endangered. Tracking declines in long-lived species like the Clanwilliam cedar is difficult due to a lack of historical data, but this study demonstrated a novel way of doing so using repeat photography.

Researchers at the University of Cape Town, led by Joseph White, tracked down 87 historical photos of Clanwilliam cedars (stretching back 80 years) and meticulously recreated these photos, creating a visual record of population changes. The photos suggest tree numbers declined significantly over this period, but also suggest which habitats are best suited to their survival, which should help focus future conservation efforts.

We covered this paper in more detail in this video blog.

Comments