Stunting, growth retardation due to chronic undernutrition in childhood, is not a topic that often appears in the popular press. As an investigator who has studied growth and stunting for close to 20 years, I felt a bit conflicted when I saw ‘stunting’ in a New York Times headline.

On the one hand, I was excited to see a rarely discussed public health problem brought to the forefront. On the other hand, it saddened me that we are still far from understanding how to prevent stunting, a condition that has lifelong implications.

Thus, the review by Said-Mohamed et al. is timely and welcome as they discussed the many intricacies that exist between the science and the polices surrounding stunting.

What causes stunted growth?

According to the World Health Organization, approximately 171 million children are stunted in the world with almost 98% of them living in developing countries. The primary cause of stunting is an insufficient intake of calories and/or micronutrients to support normal growth processes in gestation and during childhood.

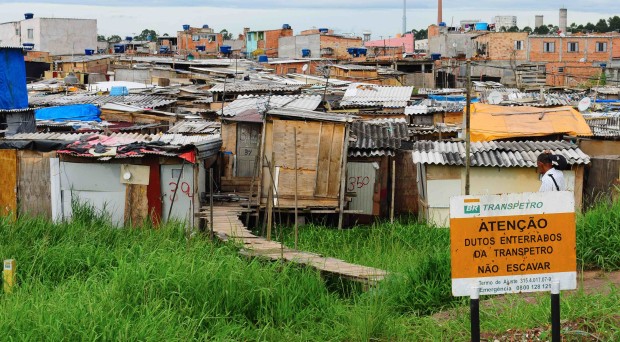

However, when one digs deeper into the reasons a child is not receiving the nutrition necessary to support proper growth, the situation becomes complex very quickly. Many of the underlying causes of poor nutrition are often related to environmental and economic conditions, such as poor air quality, infections from poor sanitation, limited access to nutritious foods, and so on.

Ultimately, one finds that it is not any one of these factors that is the ‘cause’ of stunting, but rather poverty and marginalization that give rise to the conditions that foster poor nutrition and health.

Research on metabolism and stunting (see here, here and here) clearly suggests that growth retardation in childhood results in metabolic adaptations that favor carbohydrate over fat metabolism. The lifelong health implication of this adaptation is an increased risk for fat deposition, even when total caloric intake is not excessive.

Thus, considering that many stunted children continue to live in countries now experiencing the nutrition transition, the overall risk for obesity and chronic diseases is alarming.

Economic development

As described in the review, economic development may provide the backdrop against which cognitive and metabolic challenges associated with stunting may become problematic. In Brazil, centers that previously treated wasting and stunting now find that upwards of 25% of children are treated for obesity and stunting.

For South Africa, stunting is an even more sensitive and pressing public health problem as economic development and the nutrition transition continues, but the prevalence of stunted children remains high in many regions of the country.

Moreover, the situation in South Africa highlights the important problem of ‘hidden hunger’ in which obesity may develop at the same time micronutrient deficiencies persist due to a diet of energy dense, processed foods that are low in nutrients.

Improving hidden hunger

Said-Mohamed et al. describe how standardized and new methodologies have improved our ability to monitor temporal and international changes in the prevalence of stunting in the past 30-40 years. At the same time, it is important to consider ongoing challenges that create obstacles to fully advancing our knowledge of stunting and its consequences.

Specifically, policies need to be explicit that monitoring occur in the most vulnerable populations, the informal areas that may not be part of national or local nutrition surveillance programs.

Studies on the physiology of stunting need to shift their focus to growth as a process, rather than an outcome.

As someone who has a deep understanding of the difficulties involved in studying the physiology and epidemiology of stunting, I remain committed to advancing research related to poor growth. I believe that more studies of metabolism, body composition, cognition, and social outcomes following ‘recovery’ from stunting should be developed. Perhaps even more important, studies on the physiology of stunting need to shift their focus to growth as a process, rather than an outcome.

Simply put, by defining stunting with a cutoff, we are accepting that children who are still short for their age are ‘normal’ or ‘healthy’, when they are merely less stunted than before.

Given what is known about the factors that contribute to stunting, the research community is in a strong position to influence meaningful policies to reduce the global prevalence of stunting.

What needs to be done?

An important step would be to create truly interdisciplinary research programs that incorporate related disciplines (such as engineering, microbiology and psychology) that can more fully inform scientists and policymakers.

For example, studies of the metabolism of stunted children can coincide with studies of water access, sanitation, and intestinal flora. Such interdisciplinary research would provide solid evidence of interactions between key factors contributing to stunting.

In conclusion, as transitional countries continue to experience economic development and the nutrition transition, it is more important than ever to advance policies that are more effective in reducing the number of stunted children from 171 million worldwide.

One Comment