Last week the New York Academy of Sciences (NYAS) hosted an exciting symposium Microbes in the City: Mapping the Urban Genome that was a jammed-packed day full of research science, policy discussion and glimpses into the promising future of the metagenomics field. Microbiome research aims to identify the microbial citizens of our cities, environments or any place amenable to swabbing or sampling, seemingly only limited by resources and the imagination of investigators. Microbes are everywhere; turns out, you just need to look.

Our Microbes, Ourselves

There are about ten times more bacterial cells in your body than human cells, making us more microbe than human. You have an estimated 3-5 lbs of commensal bacteria that live with you and that are essential for the proper functioning of many aspects of your biology. In that sense, you and your microbiota are a “super-organism”, with all the genes that the microbes contain and all the metabolites that they produce being part of you.

This personal microbiome has become an attractive thing to study due to recent advances in sequencing technology and data analysis, as well as the implications that the microbiome can affect things like weight gain, disease susceptibility and even mood. The mysteries of the human microbiome are being unraveled, but the high degree of complexity of these microbial communities themselves as well as their interactions with each other and their hosts remain far from being fully understood.

Our internal and topical microbiota are intimately associated with us, but obviously we also encounter microbes in the environment. What microorganisms do we come across in our daily lives? How is the microbial ecology of the urban environment affecting us? How are we affecting it? These intriguing questions have led to some very fascinating research that gives us insight into the remarkable makeup of the thriving and dynamic microbial world of the city.

Urban Genomes

“Everything is everywhere, but the environment selects”. This tenet holds true for the microbes found in soil, deep sea vents or intestines, but it applies just as equally to our urban environments, whether those be high rise buildings, wastewater treatment plants or mass transit systems. Therefore, discovering what microbes are present can in fact tell us about the environment in which they are found.

Identifying those microbes is fraught with challenges, but with the advances of genomics, we can sequence complex communities and characterize the “metagenome” of a sample, cataloguing its microbial makeup. We aren’t just talking about bacteria, either; fungi, viruses, protists and unicellular organisms also encompass an urban microbiome.

Metagenomics Detectives

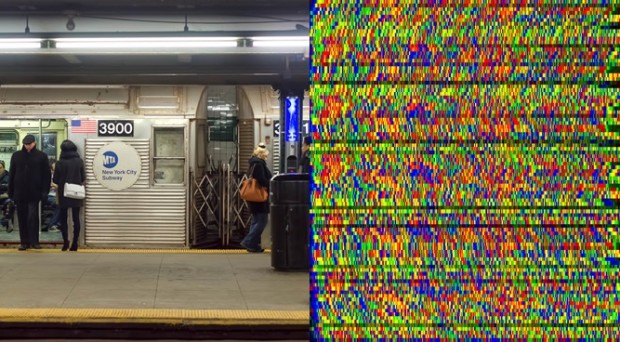

A wealth of research is being done in the area of urban metagenomics, as was highlighted at this NYAS event. Some of the scientists in this exciting field discussed their own “Urban Genome Projects”, including the sampling of New York City sewage treatment plants (Jane Carlton, New York University), the New York City subway (Christopher Mason, Weill Cornell Medical College), the Boston subway (Curtis Hottenhower, MIT), bed bug- and cockroach-infested areas (Coby Schal, North Carolina State University), the Chicago River (Rachel Poretsky, University of Illinois at Chicago), homes and hospitals (Jack Gilbert, Argonne National Laboratory) and practically the entire city of Austin (Juan P. Maestre, University of Texas at Austin).

These endeavors represent massive efforts by scientists and volunteers to accurately collect and catalogue huge numbers of samples from sometimes inconvenient or inhospitable places. Enormous amounts of data need to be processed, analyzed and stored to create a microbial profile of a particular place, and having shared, open and available resources will aid in the comparison of microbial assemblages.

The fact that urban microbiomes are being described for so many areas and environments allows us to study patterns of microbial signatures and explore their relationships with one another. In this way, intriguing connections can emerge that inform on how the mutual interactions between humans, microbes and the environment affect our health and behavior. These crucial insights into the microbiology of our world can help us to understand how the design, structure and management of our cities contribute to the organization of life at every scale.

Love for microbes

Although “germs” and “bugs” can get a bad rap, the sheer ubiquity of microbes is a very normal and very essential characteristic of our world. Urban genomics research teaches us a lot about where which microbes are found and can serve as an information tool to help us see that the widespread presence of microorganisms is a fascinating, integral part of our ecosystems, urban or otherwise.

2 Comments