Hummingbirds ♥ plants

Hummingbirds are rather unique. Found only in the Americas, they are known for their small size (the smallest known of all the birds is a hummingbird: the bee hummingbird at less than 2g), incredibly fast metabolism and ability to hover while feeding from plants (creating the humming sound from which their name derives).

It is feeding from plants, a behavior common to all hummingbirds (although some supplement this with insects), that is key to understanding hummingbird evolution. The ability to hover is necessary to gather food from flowers and being small makes this possible, while the sugar rich nectar the birds obtain supports the high metabolism needed to sustain this lifestyle.

Plants have been equally affected by this relationship. Species that rely on hummingbirds for pollination, instead of the insects their ancestors did, have acquired a number of ‘pro-bird’ and ‘anti-bee’ traits; nectar that is particularly sucrose rich, flowers that are brightly colored but unscented (smell is vital for insects to find flowers, but vision is the key for birds), and various adaptations to their flowers to allow easy access for hummingbirds.

Hummingbirds and plants represent a classic example of a plant-pollinator relationship. Some 7000 species of plants now depend for pollination on one or more of the 361 known species of hummingbird.

A deepening relationship?

Other such plant-pollinator relationships have resulted in substantial speciation; that is, new species evolve at an unusually quick rate as individual plant species adapt to their specific pollinators and diverge over time. Has the same thing occurred in the plant-hummingbird relationship?

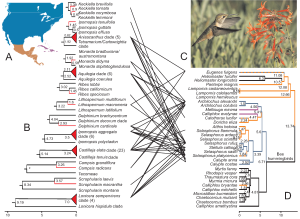

To find out, Stefan Abrahamczyk at the University of Bonn and Susanne Renner of the University of Munich conducted a wide ranging study on the evolution of hummingbirds and the plants they pollinate, the results of which were recently published in BMC Evolutionary Biology.

The researchers focused on the temperate regions of North and South America (i.e. northern Mexico upwards and the southern parts of Argentina, Chile and Uruguay) because species in these areas are much better known than in more diverse tropical regions. They gathered the available genetic data on hummingbirds and plants known to rely on hummingbirds for pollination in these regions and used this to calculate the likely dates when specific interacting plant and hummingbird species first evolved.

As expected based on previous research, South American hummingbirds are much older than their North American cousins. From their data, Abrahamczyk and Renner estimate that the oldest South American groups are approximately 15 million years old, while the oldest North American hummingbirds appeared around 6 million years ago.

In both regions, the oldest hummingbird groups are those that pollinate the oldest bird-pollinated plant groups, strongly supporting the idea that they evolved together. Notably though, in both regions the build up of plant species diversity was gradual. In general, once a plant group becomes adapted to hummingbird pollination there is not a huge amount of subsequent diversification. So while hummingbirds have certainly had some impact on plant evolution, it is less than might have been expected from such a lengthy and close relationship.

Hummingbirds are fickle partners

Why is this so? The researchers doubt this is merely due to the relatively recent evolution of the hummingbird-plant relationship. As they point out, the much older South American groups are no more species rich than the younger North American hummingbird-plant groups.

One explanation put forward by the researchers is that bird pollinators can cover much greater distances than insect pollinators, increasing gene flow between plant populations and preventing the fragmentation of populations that drives speciation.

Secondly, they speculate that it might be evolutionary inadvisable for a hummingbird to focus on a single plant species. Indeed, many hummingbirds pollinate several related plant species; for example, the North American ruby-throated hummingbird pollinates three different species of the Silene family.

This is quite different from the plant-pollinator relationship in many insect pollinated plants, where one insect species is often a specialist pollinator of just one plant species, a relationship likely to lead to further speciation. Conversely, the promiscuity of hummingbirds discourages both bird and plant from evolving further specialised adaptations, resulting in less species diversity than we might otherwise see.

The deep evolutionary relationship of hummingbirds and the plants they pollinate cannot be doubted; one could not exist without the other. Yet this new research suggests that in a certain sense the relationship is a stagnant one; without the promise of greater fidelity, plants will only change so much to accommodate their partners.

One Comment