This blog is cross posted from SpringerOpen blog

Despite tremendous changes over the last century, pastoralist communities of Northern Kenya did not experience significant social, socio-economic and political transformations. Women continued to face strict strictures because of their social position as pastoralists, colonized subjects, and females. Although there are changing gender roles among pastoral societies, women’s contributions have not been fully recognized. There has been little mention of pastoral women in the mainstream historical scholarship with the exceptions of contemporary resonances in changing roles of pastoral women done by anthropologists such as Elliot Fratkin and Kevin Smith.

The article “Colonial and Post-Colonial Changes and Impact on Pastoral Women’s Roles and Status” uses the case study of the Boraan of Northern Kenya to describe how the shift to colonial power restructured the roles and status of women. The study uses conventional archival documents to explore the impact of colonization on pastoral women’s roles. It argues that the incorporation of the Borana into the colonial state system introduced a socio-economic and political order that replaced an existing Borana social organization and became the basis of gender ideologies prevailing today.

Mapping pastoralists’ women’s roles

Pre-colonial Borana social organization was regulated by the Gada system, a genealogical organization that, in addition to structuring the social, economic, political and religious roles of men, was also a system of reckoning historical events. Within the Gada system was an institution of Siiqqee that offered women legal rights to exercise social, economic and political roles. Women were not conceived as inferior to men but rather, according to Kuwee Kumsa, each gender checked and balanced each other’s roles.

Labor was divided along gender lines through which women took care of herds kept at home in addition to other highly valued duties within the household. Borana women exercised control over the most productive resources such as milking cows and therefore they played the role of distributing milk and other dairy products. Milk was an integral part of the Borana household, not just as a source of food but likewise as a symbol of women’s social and economic power. These activities were fundamental not only to the continuity of pastoralism activities but also to the gender relations.

However, among many other forces, European colonialism in the 1890s shaped and reshaped practices of many colonized people’s cultures including Africa’s pastoralist societies who have been perceived as remote and static. Colonial rule imposed rules and regulations, control over social system, and arrangement of division of labor in the societies they encountered.

British colonization

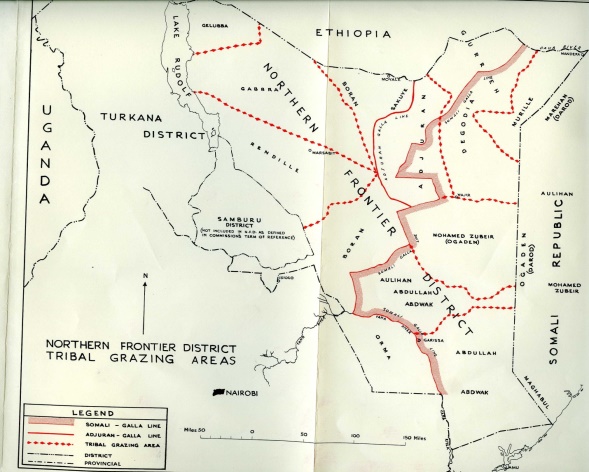

Kenya became a British protectorate in 1890, but archival research reveals general reluctance to add northern Kenya into the British sphere of influence because it is was considered dry and barren and did not serve colonial economic agenda. However, southward expansion of Abyssinian Empire forced British to incorporate the frontier to its colony in 1910. It was administered differently and dubbed Northern Frontier District (NFD).

Three key processes best explain the incorporation of pastoralists in general and Borana in particular into the colonial state. Under British rule, the administration system, taxation, commercialization and commodification of livestock policies became dominantly male venues of control. Native administration served as an example par excellence particularly in northern Kenya because the British avoided incurring the cost of administering NFD. The introduction of hierarchy of native administration fashioned new roles for men with the responsibility of maintaining local control and monitoring livestock movements including when and where to graze.

Taxation requirements placed monetary value on livestock, but the efforts to promote monetization and commoditization of livestock among the Borana in particular, intensified during the World War II. The demand to feed troops stationed in NFD coerced the Borana into selling their livestock. According to Gudrun Dahl, these placed in the hands of men the task of controlling livestock disposal and proceeds.

The new gender hierarchy and the status quo gradually altered the previous gender balance that placed an important role for women and eroded their social agency. Even the formation of African women’s group, which was part of the post-World War II social reform, grossly excluded participation of women from NFD. The places that had possibilities of forming such groups were fraught with funding biases.

Although colonial policies marginalized pastoralists, nothing illuminates colonialists’ miscalculation of pastoral women’ roles more than the account by Daniel G. Van’s memoir, Kenya’s Northern Frontier District (NFD). In a period when the very definition of women’s independence, rights, and freedom were in flux, women pastoralists demonstrated against colonial imposition of dress codes.

Since Kenya’s independence in 1963, enormous socio-economic and political changes have occurred and pastoral societies are today affected by state policies of sedentarization, population increase, urbanization, and climate change. Pastoral societies and women in particular have become targets of development policies and programs making them more vulnerable.

However, recent democratic movements, constitutional changes and Kenya vision 2030 have begun to give attention to issues facing minority pastoralists. While questioning the meaning of equalization and women’s subjugation in the age of globalization, future research will examine the agency of Borana and women in particular in dealing with changes throughout the post-colonial period.

Comments