This post was co-written with David Moher, co-Editor-in-Chief of Systematic Reviews.

While much of the focus on reducing waste in research has been on primary studies, in particular clinical trials, systematic reviews and meta analyses can compound the problem. Here, we discuss the need to apply the same standards to systematic reviews as are seen in clinical trials, including registration and publication of protocols.

So, what is the problem?

For those of us paying attention, there has been a slow, yet steady buzz for many years about the waste incurred in biomedical research. Eighty-five percent of research investment is estimated to be lost because the wrong questions are asked, inappropriate research designs/methods are used, poor regulations are in place, or researchers incompletely/inadequately report their research, or fail to publish it at all.

To date, much of the focus on waste has been around primary studies, namely clinical trials; however, most people likely don’t realize that systematic reviews, which are essential in summarizing and synthesizing primary research, not only magnify waste in primary studies, but also contribute to it much in the same way… although to a lesser extent.

Why should you care?

We are taught to think that systematic reviews provide the best evidence for answering a health research question, particularly those about therapy effectiveness. They are lauded for their rigourous, methodical approach, an essential component of which being that they are conducted according to pre-specified methods and analyses. However, in reality this doesn’t seem to be happening. Indeed, alandmark 2007 study determined that the majority of systematic reviews did not mention working from a protocol at all. Yet we still have (blind?) faith that they are all that we want them to be.

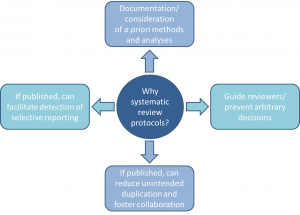

Without review protocols, how can we be assured that decisions made during the research process aren’t arbitrary, or that the decision to include/exclude studies/data in a review aren’t made in light of knowledge about individual study findings?

Without review protocols, how can we be assured that decisions made during the research process aren’t arbitrary, or that the decision to include/exclude studies/data in a review aren’t made in light of knowledge about individual study findings?

Emerging evidence suggests that when protocols are available, for example in Cochrane reviews, at least 22% have discrepant outcomes from their corresponding completed reviews, some related to the significance, size, and direction of outcome effects (much of the same story as in the primary literature). Furthermore, while some duplication is good (i.e. for validation), how can we ensure that efforts are not being simply wasted because disconnected groups of systematic reviewers are unaware of what others are doing? With all of these questions, what are we to make of reviews that don’t refer to any kind of protocol, and may not have one?

What is the solution?

If you’re having an ounce of déjà vu right now, you were probably around 30 years ago when the same concerns were being raised about clinical trials: not all protocols were reported or available, not all trials contained complete information about methods and findings, and some trials were not published at all, leaving questions about the integrity of the research that followed. The solutions that followed went something like this:

- The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guideline was published in 1996 (updated in 2001 and 2010).

- The first online trial registry (ClinicalTrials.gov) launched in 2000 (many others have since emerged, such as the ISRCTN Registry).

- In 2005, the International Committee for Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) announced that its journals would not publish trials that had not been registered.

- In 2007, registration was made mandatory for trials conducted in the US, and in 2008, ClinicalTrials.gov launched a results database.

- The Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) statement was published and the AllTrials initiative (“All trials registered; All results reported”) was launched in 2013.

Solutions to improve incomplete and biased reporting of systematic reviews have followed a similar trajectory. In 1999, the quality of reporting of meta-analyses (QUOROM) guideline was published; this was succeeded by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guideline in 2009. The first international registry for systematic reviews (PROSPERO) was launched in 2011. In 2012, the first journal dedicated to exclusively publishing systematic review products (including protocols), BioMed Central’s Systematic Reviews, was started (other journals have begun publishing review protocols as well). Now, in the first week of 2015, a PRISMA guidance for protocols (PRISMA-P) has been published in Systematic Reviews and The BMJ.

What can you do?

What can you do?

Given their costly time and resource requirements, we simply cannot afford wasted efforts when it comes to systematic reviews. Accompanying the PRISMA-P guideline, is a specific set of proposed actions (and benefits) for stakeholders involved in the systematic review process (yes, that means you!). Now that we have helped you take stock of the problem, we challenge you to do your part tohelp stop some of the waste.

Check out the latest solution to improve the reporting of systematic reviews, PRISMA-P, in more detail here.

Please, correct the link for “landmark 2007 study”.

There’s a message in PLOS of “page not found”.

wow, awesome article. Want more. oqza