We’ve recently published a paper in the journal Trials on something we’re building right now. It’s an ambitious idea, and long overdue: OpenTrials, an open, freely accessible index of all publicly accessible documents and data ever made available, on all clinical trials ever conducted.

The messy world of clinical trials

You might find it surprising that such a thing doesn’t already exist. But the world of clinical trials is currently in something of a mess, as is increasingly recognized, especially when it comes to knowledge management.

Whole trials are routinely left unpublished, which exposes the medical literature to avoidable bias and exaggeration.

Whole trials are routinely left unpublished, which exposes the medical literature to avoidable bias and exaggeration. When trials are published, the results are often misreported in academic journal articles.

You can find the same trials reporting different results in different places, and the information in journal articles has been shown to be less complete than – and discrepant with – other sources like clinical study reports.

Furthermore, key documents such as Case Report Forms and Ethics Committee paperwork are often left inaccessible, even though we know they can contain important information.

All data on all trials in one place

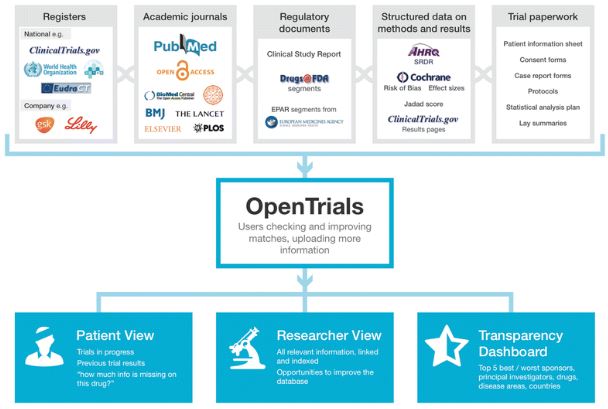

That’s why we’ve set out to create an open, freely accessible database that can store, or link to, all publicly accessible data and documents on all trials in one place; and then build user friendly windows onto this information.

This isn’t a new idea. The need for such a service has been discussed before, most notably in a blue skies editorial from 1999 on ‘threaded publications’ by Doug Altman and Iain Chalmers, and more recently in the ‘Linked Reports of Clinical Trials’ project, which allows publishers to store a unique trial ID on CrossMark, allowing all academic publications about one trial to be identified.

We’re going further than this, aiming to aggregate all information of all types in one place, threaded together by trial, as in the diagram below.

Placing all the information in one place serves two important functions. Firstly, it helps people find the things they need to make informed decisions, as doctors, researchers, or patients.

There are vast numbers of tasks that become more straightforward when you have all the information in one place, or at the very least a place where all such information can be stored, as we describe in the ‘Use Cases’ section of our paper.

But there is also, we hope, a cultural impact: when you can see that for some trials, all the key documents are publicly available, then that drives up expectations; especially when for other trials, several or all sources of information are simply missing.

Since this is ambitious, it’s worth describing a little about how we are building. It would take a vast sum of money to build a perfect, manually curated database of all information on the hundreds of thousands of trials ever conducted. Equally, it would make no sense to simply create an empty database with a sensible structure and then invite people to populate it, while the tumbleweed blows through.

A three step process

So we are initially populating the database using three methods. Firstly, we are automatically scraping the contents of various repositories of information, matching documents and data on trials as we go, using simple methods like trial registry identification number, and more complex methods like probabilistic record linkage.

Secondly, we have received donations of structured data from people who’ve already matched and curated multiple documents on clinical trials (and we’re very keen to hear from you if you have this kind of data yourself).

Thirdly, we are allowing any user to submit missing documents and data on clinical trials through the site: so if you find a trial that you participated in, and you have a copy of the Patient Information Sheet, you can upload it.

If you find a trial that you’re interested in, and you know where the Clinical Study Report can be found online, then you can give us the link to it.

If you find a trial that you’re interested in, and you know where the Clinical Study Report can be found online, then you can give us the link to it.

To be clear, we are not hosting individual patient level data from clinical trials, because this data poses privacy issues, and many other projects are doing this already: but we are linking to the people who do host this data.

The ideals behind OpenTrials

Since this is a collaborative project, it’s worth setting out some of the ideals behind it. This is entirely non-commercial. We are funded by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, informed by a generous advisory group, building with Open Knowledge, and collaborating with the Centre for Open Science.

All data will be shared as structured ‘open data’, so that everything can be freely used, modified, and shared by anyone, for any purpose. We aren’t charging for access, and we aren’t restricting re-use.

We hope that others who use the data will share their data back in turn.

We hope that others who use the data will share their data back in turn. Moreover, everyone who helps contribute to the database is fully credited, wherever the data they’ve contributed to is presented, whether that is uploading a single document, or sharing a giant datastore.

In the same spirit, we’re keen to hear any critical feedback during development. We’ve published our paper while we build, specifically because we want feature requests and criticisms as we go along, while we can still use them: that way, we can make sure that what we build is as useful as we can all make it.

We’ve already run several user engagement workshops and received hugely useful feedback, especially on additional document types and information sources that we should aim to import. If you think we can do things better, or if you think there are more data sources we should seek, then we want to hear from you.

And lastly, a personal note

OpenTrials is a collaboration between academics and software engineers. That’s something I feel strongly about: it’s why we set up the Evidence Based Medicine DataLab last year in the University of Oxford, and we’ve already launched OpenPrescribing, a service that lets you see what UK doctors are prescribing to their patients, month by month.

Projects like these use the skills of academics and coders, working together to produce live, data-driven services to improve science and healthcare, rather than only static journal publications. These live data projects are much harder to fund than straightforward academic papers, they’re challenging, and they’re very different to familiar, everyday academic work. But they can be every bit as useful. I hope you read our paper.

Comments