The fierce heat of the sun was burning. Aba wiped the sweat from her brow as she trudged through the farm entrance and emptied the cocoa beans into the designated crate. Hot and parched from carrying the heavy load. She knelt by a small cloudy pond. Not fussed by its murky appearance she cradled her hands together and slurped unceremoniously.

In the weeks that followed, Aba’s health slowly deteriorated. She was tired, her body ached and her abdomen was tender. As she hacked at the cocoa pods, she had to double over intermittently, trying to ease the storm that was brewing in her stomach. It was releasing one anguishing blow after the other. The pain would eventually subside; it was just a question of when. However, on this occasion the heaviness grew and rose upwards to her throat. She quickly ran to the bushes and was sick.

She rinsed her mouth and washed her face in a nearby stream. Gazing down at her rippling reflection below, she could barely recognize the creature staring back at her. One of her greatest attributes was her eyes, bright and round, but these had lost their shine. Now, when she saw herself, all she could see was a demon with sulfurous yellow eyes. With no education and limited health resources, Aba was unaware that she was suffering from Hepatitis E.

Hepatitis E (HEV) is a liver disease caused by the hepatitis E virus: a non-enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus. It is one of the lesser known members of the viral hepatitis group, which also consists of the more notorious Hepatitis A, B and C. It is a waterborne disease, transmitted mainly through the faecal-oral route, where shedding of the hepatitis E virus in faeces contaminates drinking water and food supplies. Poor sanitation and limited access to clean water in much of the developing world provides the prefect festering zone.

Other transmission routes have been identified. Recent laboratory analysis confirmed that a few cases in the Northern Uganda HEV outbreak were infected as a result of person-to-person transmission. Although there is no evidence in Africa that infection has arisen from blood transfusion or sexual intercourse, there are well documented cases of transfusion of infected blood products in Europe and Japan. Only one study has discovered that HEV can spread through mother-to-child transmission, but that suggests that in Egypt, 55.6% of HEV infected mothers had fetuses which tested positive for HEV.

Every year there are an estimated 20, 000,000 HEV infections, over 3, 000,000 acute cases of HEV, and 56,600 HEV related deaths. It is the most or second most common cause of acute viral hepatitis among adults throughout much of Asia, the Middle East and Africa. At present there is no vaccine, though hope is starting to emerge for one.

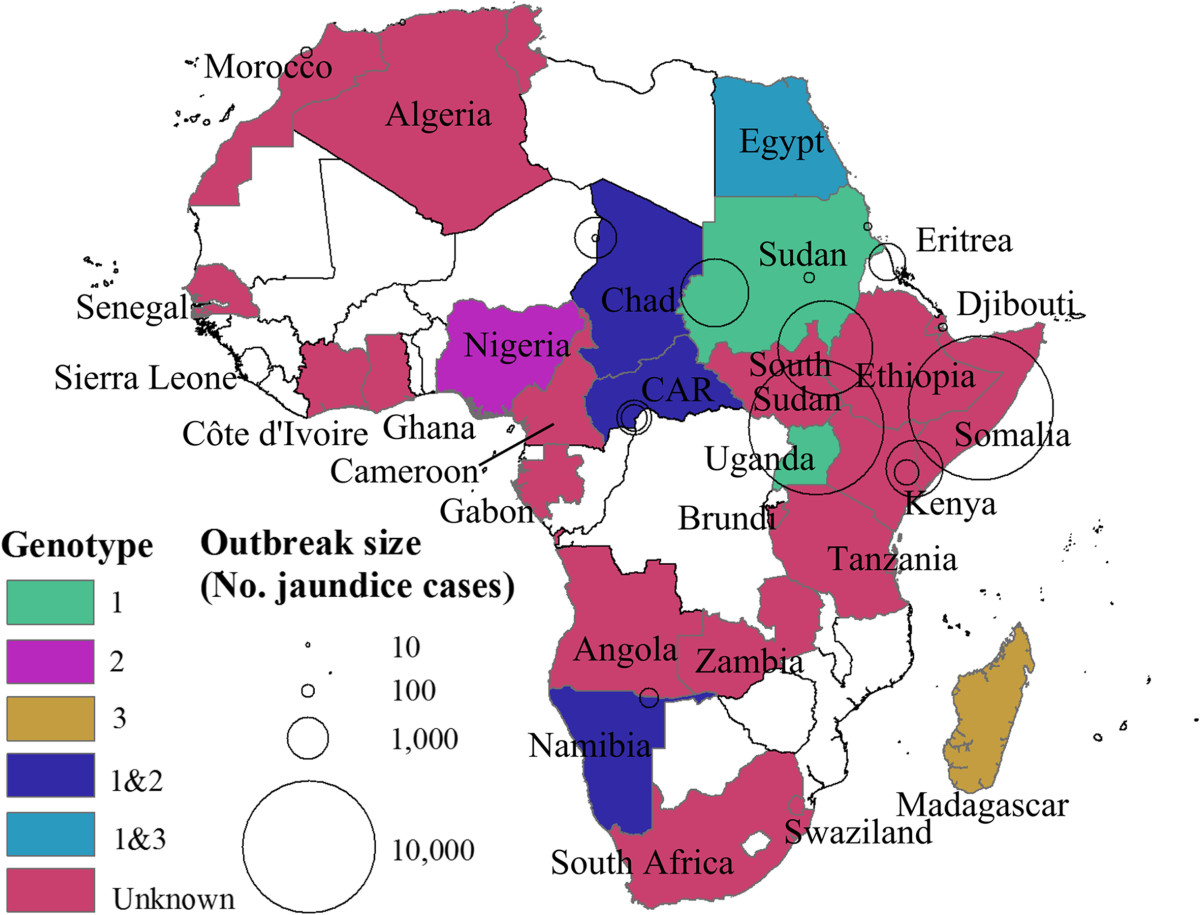

Map of Africa. Colored areas represent countries where HEV is endemic at least for some subpopulations or sporadic HEV cases or outbreaks have been detected. Circles indicate HEV outbreaks with centers and areas indicating the location and outbreak size, respectively. Different colors represent different genotypes. White areas indicate countries where no data is available. Kim et al. BMC Infectious Diseases 2014 14:308 doi:10.1186/1471-2334-14-308

HEV was once referred to by scientists as a virus with two faces because it has two distinct profiles. One profile causes large outbreaks and epidemics, resulting in high morbidity and mortality among pregnant women and young children. The other is responsible for a short lived infection, a virus that can be resolved within 3–8 weeks.

Symptomatic infection is most common in young adults aged 15–40 years. Although infection is frequent in children, the disease is mostly asymptomatic or causes a very mild illness that goes undiagnosed.

Where symptoms are seen they typically include: jaundice (yellow discoloration of the skin and sclera of the eyes, dark urine and pale stools); anorexia (loss of appetite); an enlarged, tender liver (hepatomegaly); abdominal pain and tenderness; nausea and vomiting; fever.

The effects of HEV are usually self-limiting, but in rare cases it can manifest into acute liver failure. Typically, pregnant women are at greatest risk of dying from this liver failure, and people with weak immune systems are more likely to suffer from chronic cases.

Africa is suspected to be among the most severely affected regions in the world. However, it is usually the last place where resources are deployed. Taking this into account, a team of international researchers focused their attention on understanding the patterns, causes and effects of HEV in Africa, in order to implement evidence-based control policies aimed at preventing the spread of HEV.

The team explored the rates of infection, severity, modes of transmission and circulating genotypes. They found that HEV has infected half of all African countries. Since 1979, 17 HEV outbreaks occur every other year in Africa resulting in 35,300 cases and 650 deaths.

Ultimate control of the disease boils down to increased access to safe water and sanitation and improved personal hygiene. Until these measures are universal, we must depend on a vaccine. There is emerging evidence of a safe and effective anti-HEV vaccine, Hecolin. Suitable for those 16 years of age and older, it has been licensed in China, and shows promise for tackling outbreak interventions and control of endemic disease. However, it could be sometime before this vaccine is widely available in Africa, because several epidemiological issues still need to be addressed. There are concerns over the speed and longevity of the vaccine’s protective nature. Scientists urge that these matters are quickly resolved as a vaccine could be major proponent of an African HEV control program.

Despite its substantial impact on human health, HEV has been neglected as a major public health problem. Control policies must be implemented by local, regional and international agencies to counter years of unawareness. Only then can lives be saved.

Today, 28th July 2014, is World Hepatitis Day. Every year, on 28th July, WHO and partners increase the awareness and understanding of viral hepatitis and the diseases that it causes. This year they are urging policy-makers, health workers and the public to “think again” about this silent killer.

Comments