In May 2014, the World Health Organisation declared the rapidly increasing spread of polio an international public health emergency. The virus, which usually affects children under five years old, is typically spread through faeces contaminated drinking water, causing irreversible paralysis and death in the most severe cases, where respiratory muscles are immobilised.

In May 2014, the World Health Organisation declared the rapidly increasing spread of polio an international public health emergency. The virus, which usually affects children under five years old, is typically spread through faeces contaminated drinking water, causing irreversible paralysis and death in the most severe cases, where respiratory muscles are immobilised.

Polio is currently endemic in three countries; Nigeria, Pakistan and Afghanistan, which is an amazing feat considering that polio was rife worldwide little over 60 years ago. Advances in vaccines in the 1950s, and the launch of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative in 1988, led to an enormous 99% reduction of cases narrowing the incidence of polio to just a handful of countries. March 2014 marked a major breakthrough as India was declared polio free with no reported cases for three years.

The remaining 1% however, is proving challenging despite being up against the largest internationally coordinated public health campaign in history including national governments, the World Health Organisation, various charities, private foundations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and some 20 million volunteers worldwide.

Attempts to control the remaining 1% are being hampered by a number of factors including natural disasters, terrorist opposition and migration from conflict zones. In the previous six months, 112 new polio cases have been reported from a number of countries including Afghanistan, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Iraq, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Syria.

Emergency measures have recently been put in place in Pakistan, Syria and Cameroon requiring travellers to show proof of vaccination before arriving and departing, but even this if proving more difficult than it should be with fake vaccination certificates on the rise. It seems that stronger co-ordinated efforts are required to educate people in these communities that eradication of polio will only be achieved once all children in endemic countries are vaccinated.

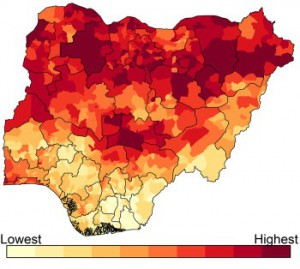

To help maximise the impact of political and financial resources aimed at polio eradication, a new mathematical model recently published in BMC Medicine by Alexander Upfill-Brown and colleagues is able to predict specific districts in Nigeria at greatest risk for future wild poliovirus cases. The authors indicate that this model could be used to target resources to maximize impact in high-risk areas and hasten polio eradication.

To help maximise the impact of political and financial resources aimed at polio eradication, a new mathematical model recently published in BMC Medicine by Alexander Upfill-Brown and colleagues is able to predict specific districts in Nigeria at greatest risk for future wild poliovirus cases. The authors indicate that this model could be used to target resources to maximize impact in high-risk areas and hasten polio eradication.

In another BMC Medicine article, Mohammad Ali and David Sack discuss a number of challenges that must be overcome to achieve a polio free world.

They discuss the need to identify high risk areas where they indicate that the model by Upfill-Brown and colleagues would be very useful. In addition, they also discuss the spread of polio from endemic countries to bordering neighbours, and the major concern that oral polio vaccine is not as effective in children in the developing countries.

This issue has been recently targeted by authors from Imperial College where they have found that a combination of an injected vaccine, and an oral vaccine, could provide better immunity, than oral vaccine alone. Whilst injected vaccines for polio were first developed in the 1950s, oral vaccines were favoured due to being cheaper, and easier to administer, especially in low resource settings. It’s thought that the revival of injected vaccines will have an important role to play in the eradication of polio, however it remains to be seen how easily they can be implemented in the endemic countries.

With just 1% to go, it seems that the race to eradicate polio is coming to an end, however the final push will require huge coordinated efforts. We can only hope these latest advances will help us get that much closer to the finish line.

BMC Medicine: passionate about quality, transparency and clinical impact

2013 median turnover times: initial decision three days; decision after peer review 51 days

One Comment