Since Ebola virus first emerged in 1976 (Zaire ebolavirus = EBOV) there have been eight outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of Congo, of which the second largest in history was declared in August 2018. By the time the outbreak was declared over in June 2020, the region had experienced 3,481 cases and 2,299 deaths.

Our new study published in One Health Outlook detected antibodies to ebolaviruses in people prior to the outbreak, suggesting exposure may be more common than previously thought, earlier cases may have been missed, and infection may not always lead to disease. Sampling also detected the first antibodies to Bombali ebolavirus in one child, first discovered in bats in West Africa in 2018, providing critical evidence that spillover of this virus from bats to humans has likely occurred. Sampling also revealed that women were significantly more likely to be positive for antibodies than men, a finding consistent with other studies where the activities of women increase their risk of exposure.

So, how can we use this information to increase our understanding of viruses and advance our ability to reduce future outbreaks?

Detecting Ebolavirus antibodies in humans

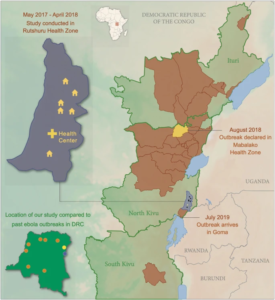

People sampled were patients seeking care for a range of clinical symptoms between May 2017 and April 2018, in the North Kivu Province of the Democratic Republic of Congo near Virunga National Park. Samples were collected and tested from 272 people (identified as male or female) ranging in age from 2 to 68 years. None were diagnosed with hemorrhagic fever at the time of treatment or had been previously diagnosed with ebolavirus infection or disease.

Of the 272 patients sampled, 30 were seropositive (antibodies present) for ebolaviruses (EBOV = 29; BOMV = 1).

Understanding exposure: The link between behavior & risk

Demographic and behavioral information was also collected to identify risk factors for exposure. Livelihoods mainly consisted of crop production. Limited contact with wild animals (e.g. non-human primates, bats) was reported but contact with rodents and domestic animals (e.g. goats, sheep, dogs) was common.

Although both sexes tested positive for antibodies, as mentioned above, women were significantly more likely to be positive, and children (2-17 yrs) comprised 45% of the positives. This finding is consistent with other infectious disease studies demonstrating women have been shown to have an increased risk for exposure, likely due to their gender roles – caring for children, the sick, and for animals. Children are also likely coming into contact with wild animals more frequently through hunting and play behaviors, increasing their risk of exposure.

Can antibody detection help prevent future outbreaks?

Detecting antibodies before or between outbreaks can help understand the geographic exposure to viruses. Spillover is likely more frequent than we realize and recognizing that spillover doesn’t always lead to outbreaks is important, reinforcing the need to study and understand viral infection and exposure between outbreak events.

The fact that women and children were more likely to have antibodies suggests that awareness of the human behaviors that increase the risk of exposure is critically important to understanding how and when exposure may occur. When we understand the connections between human behavior and viral exposure we can begin to break those connections and reduce outbreaks.

Comments