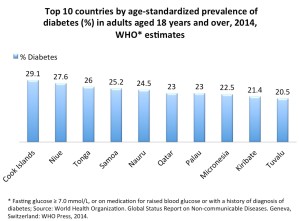

Islands often conjure, in the minds of non-islanders, notions of idyllic communities – sustained from land and sea, supporting healthy lives in union with the environment. In reality nowhere on earth is the contemporary burden of diabetes more visible than in island nations. Pacific Island nations, for instance claim 9 of the top 10 spots in the ranking of countries by diabetes prevalence (see figure below).

How is this possible?

Pacific cultures have ancient histories of extreme exploration and migration across vast expanses of ocean, strong values on traditional forms of recreation and sustenance that prioritized working physically with sea and mountains, with banquets of locally-grown foods high in micronutrients and energy, like reef fish, breadfruit, taro, and coconut.

Early photos and drawings of Pacific peoples show a lean, active, and healthy population that thrived in a challenging and isolated environment. How then did the Pacific Islands become one of the most intransigent diabetes hot zones on the planet?

In my experience working throughout the Pacific and the Caribbean, several common conditions seem to relate to the emergence of distinct diabetogenic environments, that may differ from those found in wealthier, larger countries.

First, many islands have been colonized, or otherwise occupied, by other nations and cultures, recently and throughout their history.

This colonization frequently devalued, and aimed to eliminate, local languages, foods, and cultural traditions. These languages, foods, and traditions evolved within a particular environmental context (especially important in isolated island communities), typically well-suited for the populations living within them.

Over time, agriculture and commerce in colonized island communities shifted to serve the needs of the colonizing nation, replacing local practices and products, like eliminating traditionally-maintained taro patches with cash-cropped rice fields.

Frequently, colonizing nations dominate local markets, shifting to cash economies, with products derived in or otherwise benefiting the colonizer. Hence, we have long-established local markets in many Pacific Island communities for products like SPAM, tinned meats and fish, soft drinks, candy, and ramen noodles.

It has always struck me as an odd paradox throughout the world when communities sell locally-abundant micro-nutrient-rich food, like reef fish in the Marshall Islands, on global markets to raise cash, ostensibly to then cover local costs for foods like canned tuna and colas.

This historical disruption of local systems in fragile isolated environments leaves inequitable, frequently dysfunctional and typically not sustainable local economies intricately connected to globalized ones.

So, diets change, and along with them, not only does the food system become less local and less sustainable, but also the nutritional content consumed changes in ways often not suited for the environments where populations live (for example, carbohydrate-rich diets in environments where protein-rich diets are more useful).

Another paradox as a result of these processes is that some in island communities view traditional foods as old-fashioned, not desirable, and associated with poor financial status. Packaged and prepared foods are often more desirable socially, their consumption sometimes perceived as indicating progress and wealth for a family.

The second major component of the creation of island diabetogenic environments is a dramatic shift in physical activity, integrally connected with shifts in social and economic relationships previously described as traditional economic and recreational activities (largely agriculture, fishing, dancing, indigenous sport).

As community work shifted toward cash economies, participation in traditional forms of recreation also shifted, commonly with an increased pressure on family members to work and generate cash to cover expenses.

Finally, as time becomes a rare commodity, people transition from walking from place to place to motorized transport to get to their destinations sooner. The combination of a rapidly shifting diet, loss of traditional activity, and increase in motorized transport proves lethal for populations, especially regarding diabetes.

Cultural and economic forces are formidable in populations, and prevention requiring deliberate lifestyle change proves challenging and often ineffective. The diabetes epidemic occurs in exactly the locales where the health systems are frequently least likely to be able to keep pace with the burden.

Diabetes is a complex disease requiring routine monitoring, medical and therapeutic intervention, and lifestyle change to reduce risk for complications. Where health systems are fragile or fragmented, these services are often not available nor affordable. Throughout the Pacific Islands it’s quite common to see folks with limbs amputated or blinded as a result of diabetes not adequately treated.

What to do?

Something has to change, and that change needs to start with and engage those most directly affected: local communities. People need access to affordable foods, recreational opportunities, and programs to help them prevent disease. Researchers need to help identify what works best in local circumstances, and health systems need to be innovative in providing care that communities can access. These processes are not easy and occur in a complex web of globalization.

I am heartened to see strong, locally-generated movements to restore traditional sport, cultural events, and local foods in island communities, such as those found throughout the Pacific.

Not only do these efforts strengthen health and reduce risk, but they also rekindle local cultures, values, and traditions that connect people to one another and to their environment. I’ve seen great pride and enthusiasm when cultural strands, especially those relating to food and recreation, re-emerge in communities facing health crises as many Pacific communities are experiencing.

A local colleague in the Pacific recently sent me an email, wanting to know how to go about encouraging folks in the community to eat fresh noodles made from taro, fish, banana, yam, and other local foods. He is certain there are health benefits to this sustainable diet, and wants evidence to evaluate that and to gain traction with and respect from opinion leaders who can shape local practices. These foods are readily available and connect islanders to both their environment and their past.

Much press has been appropriately generated around climate change and the potentially drastic impact it could have on island communities, especially those islands located within the vast Pacific region. These concerns are real and tangible, as the ocean seems to be enveloping the communities that we work with.

Much more immediate, urgent, and critical, in my view, is that one-fifth to one-quarter, sometimes more, of the adult population in some Pacific Island nations have diabetes. That fact threatens island populations now, creates unnecessary suffering and death now, and puts nations at risk for an unsustainable future now.

The diabetes epidemic is real and devastating in island communities. Island populations evolved to survive and thrive in their environments. Turning to the environment to help reconnect communities with their custom ecosystem resources and cultures, in particular with local foods and recreation traditions, could well be a major, powerful force toward restoring health.

3 Comments