This blog has been re-posted in Spanish on the IS Global website.

Well it’s official. The governments of the world have committed to ending HIV, tuberculosis and malaria, but merely ‘combatting’ viral hepatitis.

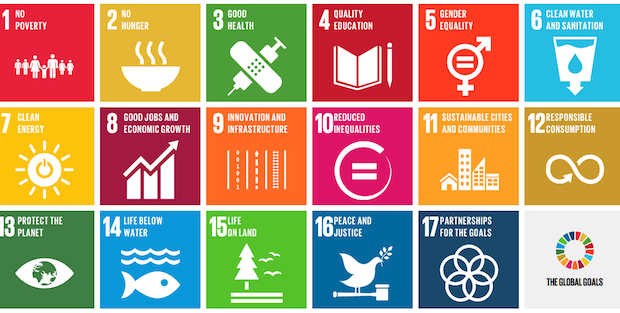

When the United Nations General Assembly voted to adopt the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) on 25 September, I don’t doubt that advocates of many stripes were left feeling that this highly influential agreement did not sufficiently recognize the urgency of their claims.

It is not my intention to argue that viral hepatitis advocates have been short-changed any more than those who care deeply about other issues. I do, however, think it is important for everyone committed to ending viral hepatitis to think about what this aspect of the SDGs means to us.

Goal 3.3 reads: By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases.

It is estimated that combined mortality from hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) exceeded HIV-related mortality in 2013.

It is estimated that combined mortality from hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) exceeded HIV-related mortality in 2013. HBV, unlike HIV, can be prevented with a vaccine. HCV, unlike HIV, is curable. How can it possibly make sense to aspire to end HIV and not also HBV and HCV?

The question is irrelevant, because the complex years-long consultation and negotiation processes that gave rise to the SDGs were not about applying this lens. While the SDGs are intended to present a unified and holistic development vision, efforts to acknowledge the priorities of a vast array of interest groups have resulted in a final document that might be metaphorically described as an extremely large patchwork quilt assembled under duress.

In this context, rather than criticising the Member States of the United Nations for failing to recognize the immensity of the threat posed by viral hepatitis, perhaps we should see it as a sign of progress that viral hepatitis – not mentioned at all in the Millennium Development Goals – is now present. After all, even though new epidemiological evidence has greatly aided our advocacy efforts in recent years, it is taking longer than any of us would like to get the word out to policy-makers and the general public about the immense burden of hepatitis.

I am quite certain that the growing momentum in our field will catapult viral hepatitis into the mainstream public consciousness within the next two to three years.

I am quite certain that the growing momentum in our field will catapult viral hepatitis into the mainstream public consciousness within the next two to three years. When that has happened, and the drive toward elimination has become a recognized element of the global health landscape, the use of the verb ‘combat’ in SDG 3.3 will mark the viral hepatitis goal as essentially outdated.

But in the meantime, we have urgent business – urgent because indicators for measuring progress on the SDGs will most likely be determined between now and March 2016. We have the opportunity to speed along the process of making efforts to ‘combat’ hepatitis seem outdated by insisting on explicitly elimination-oriented indicators for HBV and HCV.

A United Nations Statistical Commission subgroup is in the process of developing draft SDG indicators to submit to the General Assembly, and it will next convene in Bangkok in late October. The clock is ticking. How can we work together to secure SDG indicators that will embody the reality that the elimination of viral hepatitis is within reach?

Hepatology, Medicine and Policy is now accepting submissions on this and related issues. For more information, visit: www.hmap.biomedcentral.com.

3 Comments