The COVID-19 pandemic has turned attention once again on the importance of preserving ecosystems. Habitat alteration is one of the main causes of so-called “spillover” events, for example, deforestation and urbanization reduce the habitats of many wild species and increase the possibility of human contact. Malaysian Borneo is an area undergoing rapid environmental change through the conversion of forest to agricultural land, and in Sabah, a clear association has been established between deforestation and the increase in Plasmodium knowlesi malaria infections in people. This was shown in a study conducted by Dr Kimberly Fornace from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Dr Fornace used hospital records of P. knowlesi infections and environmental variables derived from satellite remote sensing data to detect a positive association between P. knowlesi incidence in humans and current forest cover and historical forest loss in surrounding areas. Plasmodium knowlesi has the potential to cause severe disease and fatalities in humans and most studies thus far have focused on the mosquito ecology associated with human infection. In this blog, however, we will describe a study investigating the transmission and maintenance of infection within the reservoir host, a population of long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis), undertaken at Danau Girang Field Center (DGFC) in Malaysian Borneo, in collaboration with the University of Glasgow and the Universiti Malaysia Sabah.

The field site

DGFC is located in the Lower Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary (LKWS), a seven-hour drive and 40-minute boat ride from the main city in Sabah, Kota Kinabalu. This study site was selected because the LKWS is home to hundreds of macaques, allowing the investigation of mosquito vectors biting macaques in the absence of humans. Here, we could find out about the abundance and diversity of potential vector species, and about the malaria infections present in mosquitoes and in macaque stools in order to build a clearer picture about macaque-to-macaque malaria transmission.

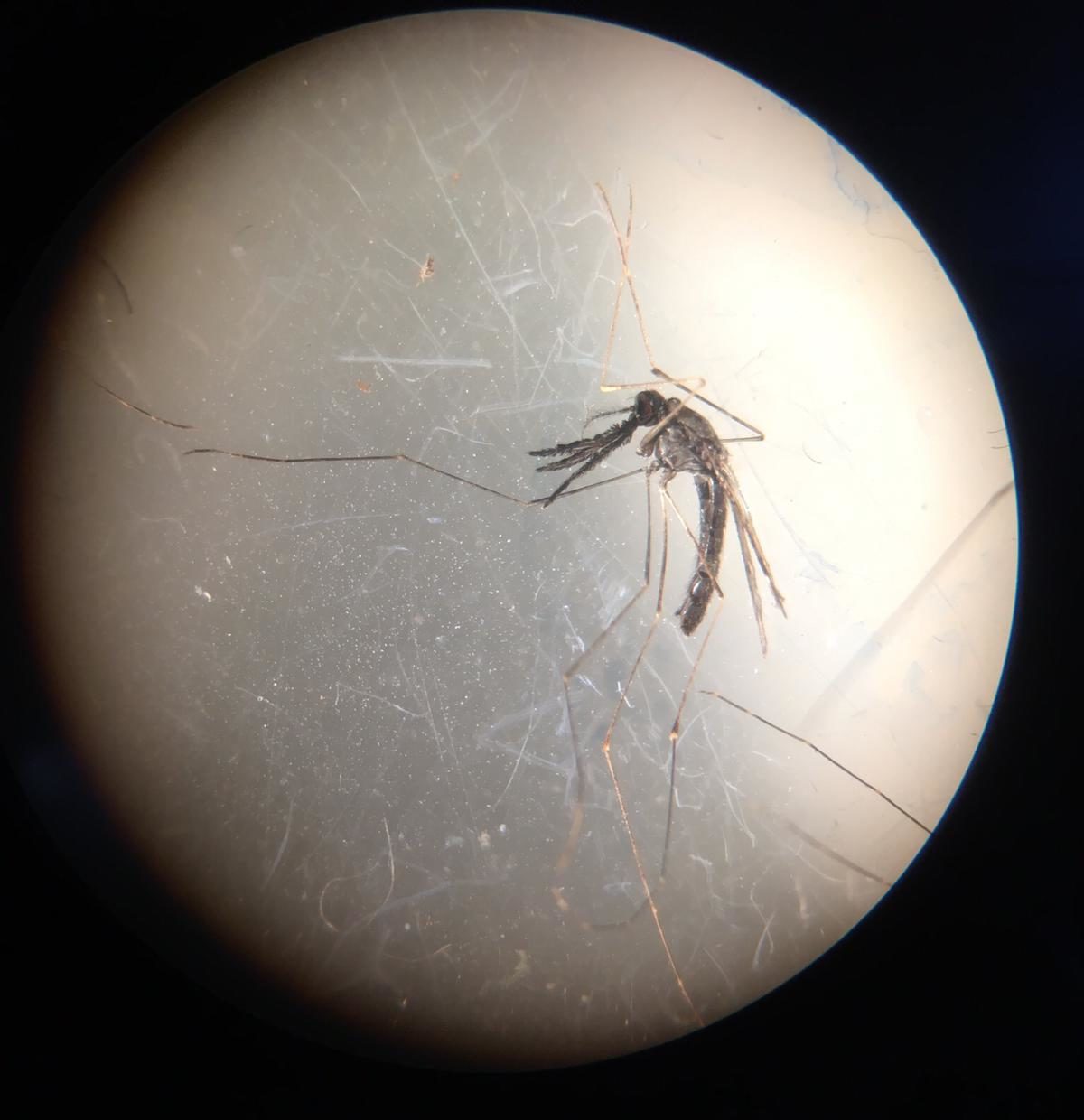

Trapping mosquitoes

We used commercial Mosquito Magnet traps, positioned at the base of trees used by long-tailed macaques as sleeping sites along the Kinabatangan River, to catch mosquitoes feeding in the vicinity of long-tailed macaques. We worked with Amaziasizamoria Jumial (Maz), a primatologist and Masters student at Universiti Malaysia Sabah who scanned the river banks with a thermal imaging camera to locate trees where macaques were deciding to sleep for the night. Wading through the mud, we placed one trap at the base of a sleeping site each night and another at a control tree of the same species and structure but free of monkeys. The subsequent morning, we returned before sunrise (before the monkeys were awake) and Maz used her thermal camera to estimate macaque abundance at sleeping sites from the boat. We then collected the mosquito traps and macaque stools from around the sleeping site to be screened for malaria infections back in the lab.

The fieldwork after dawn was accompanied by sounds of gibbons, proboscis monkeys crashing tree to tree, macaques scampering along the river-banks and hornbills flying overhead. We would often disturb large salt water crocodiles resting on the mud and one morning a herd of pygmy elephants crossed the river before us in the dark. On our return from the site, we hung back as two adults helped a newborn cross by sheltering it from the strong current.

Our findings

The mosquito magnet traps were a reliable method for sampling malaria vectors host-seeking near macaque sleeping sites. The P. knowlesi vector, Anopheles balabacensis, was caught in low abundances, but significantly more were trapped at long-tailed macaque sleeping sites than at control sites where macaques were absent, indicating a propensity for feeding on this host species. A high Plasmodium prevalence was detected within macaque populations through screening of stool samples, however no P. knowlesi was detected. Additionally, no P. knowlesi was found in mosquitoes, but two An. balabacensis had Plasmodium inui infections, thus P. inui may be circulating at high prevalence in macaques at LKWS. Currently, natural transmission of P. inui has not been detected in people in Sabah, but due to the infections detected here and in An. balabacensis trapped around human settlements in previous studies, it provokes an awareness of its potential for future spillover into humans.

Conclusions

A key finding from this study is that the Mosquito Magnet Independence Trap successfully catches vectors of primate malaria feeding on long-tailed macaques and thus can be a valuable surveillance tool to monitor infections circulating in wild monkey populations. No P. knowlesi were detected in mosquitoes or in macaque stool samples which may mean this type of malaria is not present in all macaque communities. Some people suggest culling macaques to remove the malaria reservoir host altogether, however heterogeneity in infections suggests that this method could be inefficient, as well as being highly unethical.

To reduce the risk of future outbreaks, the next steps following identification of vectors posing a risk of infection in the area, would be intervening with mosquito control techniques such as targeted insecticide spraying or application of spatial repellents.

For decades many have been ignorant of the interrelationship between biodiversity, land use, and emerging infectious diseases. COVID-19 has highlighted the need to investigate the role of biodiversity in pathogen transmission and for a more vigilant attitude towards potential zoonoses. Countries should also have adequate monitoring, preparedness and response plans in place. Natural infections of Plasmodium cynomolgi have been detected in people in Malaysia but, as yet, this has not been reported for P. inui. However, these malaria species are the most prevalent in macaques and mosquito vectors in Malaysia. As human infection with these species is likely to cause a more benign disease than P. knowlesi due to their slower replication rate, infection in people may go undetected. Therefore, surveillance of infections in humans and vectors nearby human settlements is necessary going forward to quickly detect any spillover of P. inui or P. cynomolgi into humans.

Comments