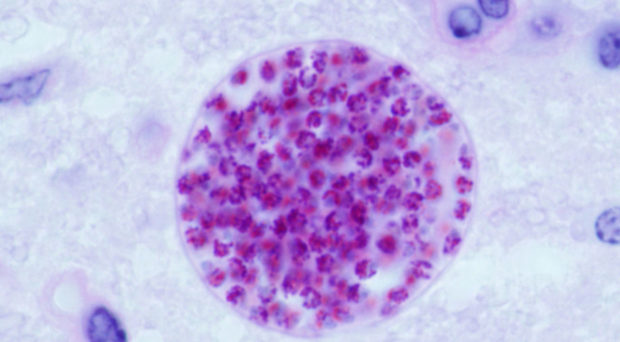

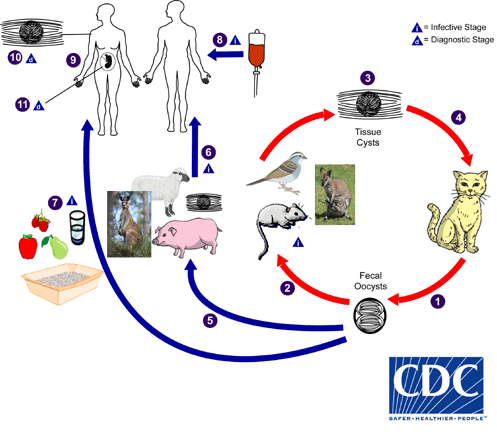

The protozoal parasite can be transmitted via the faecal-oral route, as well as through ingestion of contaminated meat products, or by crossing the placental barrier from mother to baby.

Although virtually all warm-blooded animals can play host to T. gondii infection, only infected felines act as definitive hosts – meaning that sexual reproduction (production of oocysts) and transmission via the faecal-oral route can only occur if a feline is involved in the life cycle. However, the life cycle can continue via consumption of raw/undercooked meat containing T. gondii cysts present in the tissues, and is the most common way toxoplasmosis occurs in humans.

As meat consumption is expected to increase over the next few generations (due to increasing population sizes), and as we encroach further into the habitats of wild animals to expand our farms and cities, the emergence and resurgence of zoonotic diseases such as T. gondii in humans is also expected to increase.

The vast majority of infections are asymptomatic and pose no real threat to human health. However, this cannot be said for persons with compromised immune systems or those that are recently pregnant, where the possibility of severe symptoms and neurological complications increase.

It’s been shown that over 50% of pathogens that cause disease in humans have zoonotic origins and are derived from wild animal pathogens.

Therefore, accurate and detailed surveillance of T. gondii and other zoonotic diseases affecting humans will also be of increasing need, as the swift recognition of emerging/re-emerging infectious diseases will be one of best defences in protecting human health.

A recent paper by Jitender Dudey and colleagues reviews decades of research into the epidemiology, genetic diversity, and clinical disease manifestations of T. gondii in Australasian marsupials.

The study summarises this research within free-living (wild) marsupials in Australia, as well as those present in zoos worldwide, and includes marsupials such as Koalas, Wallabies, Kangaroos, Wombats and Quolls.

Free-living (wild) marsupials vs captive marsupials

It’s been known for decades that Toxoplasma can cause serious illness and death in marsupials. However, most free-ranging marsupials establish chronic infections without clinical signs, a departure from their captive counterparts, who appear highly susceptible to clinical toxoplasmosis.

It has been proposed that the different genotypes of T. gondii found in free-ranging vs captive marsupials may underpin this trend, as most deaths in captivity occur because of disseminated toxoplasmosis (cysts spread around the body, often infecting several organs; including brain tissues).

Genetic diversity

Differences in the genotypes of T. gondii between free-living and captive marsupials have been identified, which may reflect the diversity of genotypes circulating globally, and may help explain the differences in disease severity seen between free-living and captive marsupials across the world. The authors note that the level of cross-fertilisation and recombination between genotypes of T. gondii in free-living marsupial populations is of particular concern, as these processes would further increase the genetic diversity of parasites circulating in the wild, and increases the chance of new, highly virulent genotypes being produced.

Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus)

An investigation into the seroprevalence of T. gondii in South Australian Koalas revealed a distinct lack of antibodies against T. gondii. The authors suggested this may be due to the herbivorous and arboreal lifestyle of Koalas, which lowers their likelihood of exposure to oocysts in feline faeces.

Wombats (Vombatus ursinus), Wallabies (Petrogale penicillata) & Quolls.

The suggestion that Koalas are at negligible risk of infection due to their lifestyle and habitat is supported when investigating toxoplasmosis infection in ground-dwelling marsupials, such as wombats and wallabies. One study found 4.6% of wallabies sampled in Queensland and 8% from Tasmania were determined to be positive for antibodies against T. gondii. Eight free-ranging wombats found deceased in the wild were all diagnosed post-mortem with fatal toxoplasmosis. As for quolls, a staggering 71% of spotted-tail and 58% of eastern quolls were positive in one study, whereas 5-100% of 290 quolls sampled from four sites in another study were seropositive. Prevalence rates were found to be directly associated with the presence of feral cats in the area.

Kangaroos

Similar examinations of T. gondii infections in the free-ranging Western grey kangaroo (Macropus ocydomus) from seven and four sites around Perth revealed that 34/219 (15.5%) and 20/102 (19.7%) were positive for infection, respectively. In addition to infections picked up via the environment, fatal toxoplasmosis has also been previously observed in two young, pouch-bound joeys, thus confirming the occurrence of vertical, transplacental transmission of T. gondii in marsupials.

Possible public health consequences

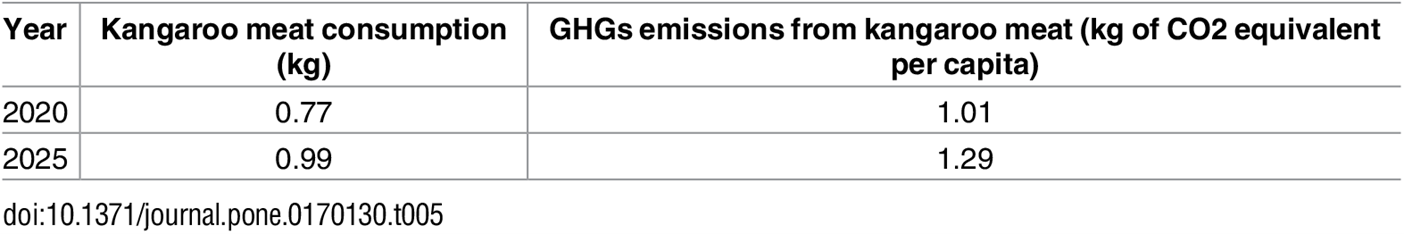

The high prevalence of T. gondii infection in most Australasian marsupials, especially in kangaroos, is of particular public health interest. As of 2011, the Australian government estimates that 34.3 million kangaroos live within the commercial harvest areas of Australia, with wild-caught kangaroo meat being exported to over 60 markets across the globe.

Due to T. gondii’s standing as one of the most common parasites of humans and animals worldwide, consumption of raw or undercooked infected meat can be a source of infections for humans worldwide – especially as human consumption of kangaroo meat is on the rise.

Therefore, close monitoring of toxoplasmosis originating in wild animal populations, such as marsupials, is essential if we intend to prevent future outbreaks before they happen.

Comments