Sheep and goats are widely kept in Tanzania and are a major source of food and income for pastoralist livestock keepers. However in recent years, livestock keepers have complained of a devastating neurological condition, known as ‘ormilo’, affecting their flocks, leading to circling, disorientation, seizures and death in affected animals.

We were working on a project investigating other livestock diseases in Tanzania when ormilo first came to our attention. In focus groups, farmers living in pastoral areas ranked ormilo as one of their top-five animal health concerns. Farmers reported that the number of cases had increased dramatically in recent years but no one knew what was causing ormilo and no effective treatment had been found. Instead, farmers cut their losses and resorted to selling affected animals for slaughter as soon as they showed early signs of the disease.

The level of community concern about ormilo gave us pause for thought. What could be causing this disease? We considered various options but one disease – cerebral coenurosis – stood out as the chief suspect for the disease problem that we were seeing.

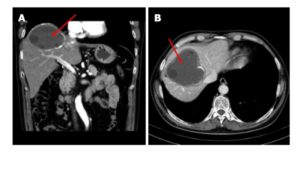

Cerebral coenurosis, also known as ‘gid’ in the UK, is a disease of the nervous system of sheep and goats caused by infection with the larval stages of the cestode tapeworm, Taenia multiceps. Infection with the parasite causes large fluid-filled cysts to form in the brain and spinal cord, which are easily visible to the naked eye . A few years earlier, reports of cerebral coenurosis in sheep and goats had emerged from local abattoirs in Tanzania, which led us to suspect that cerebral coenurosis may be an important contributing cause to the syndrome of ormilo being reported in pastoral communities. So, in response to growing community concern, we launched an investigation in four of our study villages to determine the cause and extent of this disease problem.

The results of our investigation, published in the Veterinary Record last month, were shocking. Farmers reported that between 10-34% of their flock had been affected by ormilo within the previous 12 months. This translated to more than 10,000 animals in our four study villages alone. Post-mortem examinations were conducted on a sample of affected animals and confirmed our suspicions – cerebral coenurosis caused by T. multiceps infection was detected in more than 80% of animals showing evidence of neurological disease on clinical examination.

T. multiceps is a parasite with an indirect life cycle . The adult tapeworm lives in the gastrointestinal tract of dogs (the definitive host), which shed the eggs into the environment when they defaecate. Sheep and goats (the intermediate hosts) then ingest these eggs from contaminated pastures and water sources. The parasitic larvae hatch and migrate through the bloodstream to the central nervous system where they form the characteristic fluid filled cysts known as coenuri. Ultimately, infection is fatal in sheep and goats. Dogs then eat the cysts via consumption of the carcass of infected animals, which completes the life cycle.

People may also become infected with T. multiceps if they ingest the infective eggs. Although rare, human cases have been reported, with patients typically present with headaches, vomiting and other neurological signs resulting from the cyst formation. Perhaps more worryingly, T. multiceps often co-occurs with another zoonotic cestode parasite – Echinococcus granulosus. Whilst T. multiceps infection is relatively unusual in people, infection with E. granulosus, also known is cystic echinococcosis or hydatid disease, is common and a major but neglected public health problem worldwide.

T. granulosus and T. multiceps share a very similar life cycle, with dogs as the definitive host and small ruminants as intermediate hosts. Human infection with E. granulosus leads to the development of cysts (known as hydatid cysts) primarily in the liver and lungs, although other organs can be affected too. Unlike T. multiceps cysts which typically cause clinical signs within months following infection, E. granulosus cysts are slow growing and may remain asymptomatic for many years before the infection is uncovered.

East Africa is thought to be a particular hot-spot of infection with E. granulosus but data from Tanzania are scarce and outdated. Studies conducted in pastoral communities in 2003 reported an incidence of 10 cases per 100,000 people. However, this was back in 2003 and before the emergence of Taenia multiceps as a major animal health concern amongst these communities.

This emergence of T. multiceps infection as a major cause of mortality in sheep and goats has led us to ask – is this an early warning sign of a hidden parasitic disease problem in people in Tanzania? If so, we could be sitting on a huge public health problem just waiting to emerge. Right now, we don’t know the answer to this question but we think we should try to find out…

Comments