Candida auris is an emerging pathogen that has many hospitals and health agencies worried across the world but, unlike recent cases of Zika or Ebola, it is not a virus or bacterium (such as in the case of MRSA). It is in fact a fungus.

We rarely think of fungi as particularly dangerous to humans, but we are wrong to underestimate their pathogenic potential; it is thought that more people die each year from fungal infections worldwide than from malaria.

At the end of June, both the US CDC and Public Health England issued guidance on C. auris, a multidrug resistance yeast that has been identified as the pathogenic source of infections in the UK, Japan, South Korea, South Africa, Kuwait , India, Pakistan, Venezuela, Colombia and US.

C. auris was first identified in the ear of a patient in Japan in 2009 – hence its name – but the first strains were thought to have emerged in South Korea in 1996. However, DNA fingerprinting of isolates from different countries suggest that C. auris strains emerged in different regions across the world at about the same time.

C. auris was first identified in the ear of a patient in Japan in 2009 – hence its name – but the first strains were thought to have emerged in South Korea in 1996. However, DNA fingerprinting of isolates from different countries suggest that C. auris strains emerged in different regions across the world at about the same time.

C. auris infections have typically occurred in hospitals where a patient’s immune system is already weakened or they have been taking antimicrobials that have allowed opportunistic fungal infections to take hold. Infection leads to candidaemia – manifesting in flu-like symptoms, chronic fatigue, confusion and wound infection. Severe cases lead to septicaemia (blood infection) and death. Hitherto, up to 60 % of infected patients have died, but the high death rate may be more of a consequence of complications from a patient’s pre-existing illnesses rather than from the yeast infection itself.

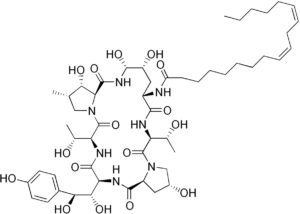

Most cases have been treated with the antifungal, echinocandins, but as multidrug resistance becomes more prevalent, treatment is with high doses of multiple antifungals.

Most cases have been treated with the antifungal, echinocandins, but as multidrug resistance becomes more prevalent, treatment is with high doses of multiple antifungals.

Measures are being put into place in hospital settings – where risk of infection is highest – to control the spread of the pathogenic yeast, but it is proving difficult to contain, as seen in the case of an English critical care unit where the yeast outbreak that started in Spring 2015 is still not under control.

Perhaps it is not that surprising we have become complacent in the presence of fungi because, after all, we eat fungi (mushrooms) and yeasts have been useful in the brewing of beer and baking of bread for so long, that it has become quite simple to forget, ignore or underestimate their potential pathogenicity. However, the emergence of C.auris as a pathogen – a drug-resistant one at that – means that fungal pathogens are not so easy to ignore.

2 Comments