Humans & their parasites

We are a parasitized bunch of apes. Oh yes! Humans have evolved carrying lots of little organisms with us; our history and their history, our evolution and their evolution, intimately linked together. How humans first acquired these parasite species is an interesting topic and based on their evolutionary origin there are two groups of parasites infecting humans: ‘Heirloom’ and ‘Souvenir’. You can guess what these mean; ‘Heirloom’ parasites, like that decrepit figurine or jaundiced doily making its way through generations in your family, are acquired by humans through a common primate ancestor. Whereas ‘Souvenir’ parasites, like that hideous bit of tourist paraphernalia your partner inexplicably brought home from your last holiday, are more recent acquisition having found their way from different animals into humans most likely through increased contact and proximity to animals such as via animal domestication.

As Machiavelli put it, “Whoever wishes to foresee the future must consult the past”, understanding how parasites have spread and switched hosts gives us both useful insights to the dynamics of evolution and arms us with potential tools to prevent and control the parasites of today. A recent paper by Hawash et al (2016) investigates the evolutionary and demographic history of a prevalent group of parasitic nematodes of the Trichuris genus, also commonly known as whipworms.

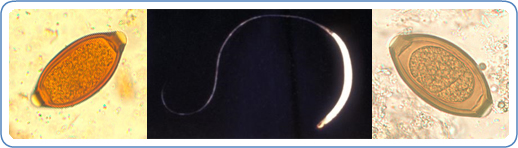

Trichuris and trichuriasis

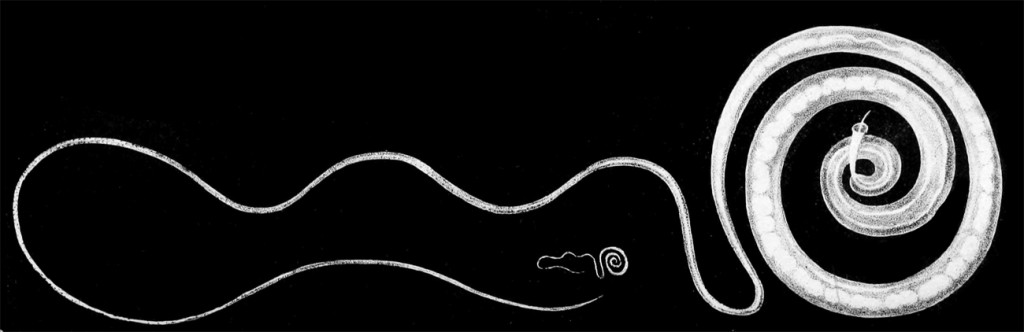

There are over 20 species of Trichuris known to infect a wide range of mammalian hosts. Though life cycles tend to vary from species to species generally this involves adult worms reproducing in the intestine, eggs released into the environment via stool and transmission occurring through ingestion of these eggs. Two species of particular interest due to their widespread prevalence and medical importance are;

- Trichuris trichiura, the human whipworm, which infects over 460 million people worldwide and is part of a group of prevalent and often co-occurring human parasites called soil-transmitted helminths, a major neglected tropical disease (NTD). Disease in humans is often associated with heavy worm burdens leading to anaemia, weight loss, nutritional deficiencies and stunted growth and development in children, the passing of painful and bloody stool, diarrhoea as well as rectal prolapse in severe cases.

- Trichuris suis, aka the pig whipworm, particularly prevalent in young outdoor reared pigs. Organic bacon from happy outdoor reared pigs anyone (“Organic” can mean parasitized)? Similar to that in humans, disease in pigs is linked to worm burden, resulting in diarrhoea, anaemia, anorexia, and chronic illness. T. suis can also, on occasion, infect humans and this has led to some interesting research & clinical trials using T. suis to alleviate a variety of autoimmune and inflammatory disorders such as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, asthma e.t.c. This is now termed helminth therapy or worm therapy (do not try this at home kids!) .

A population genetics approach to whipworm evolution and demographic history

The evolutionary and demographic history of whipworms is poorly understood. Trichuris spp. are assumed to be heirloom parasites mainly due to their presence in primates and because eggs have been found in ancient human stool at archaeological sites predating animal domestication. However there is a need of further genetic studies to elucidate the evolutionary origin and spread of whipworms. In a recent paper by Hawash et al (2016), a phylogeographic and population genetic approach was used to elucidate the epidemiological & demographic history that led to the introduction and spread of Trichuris spp. to new areas and new hosts, providing genetic evidence of Trichuris as an heirloom parasite of humans, originating in Africa.

In this study the authors investigated the genetic & evolutionary relationship between human, non-human primates and pig derived Trichuris parasites from different continents. After confirming the species of whipworms using PCR-restriction fragment polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) of the internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS-2) DNA region, all worms were sequenced using two mitochondrial genetic markers nad1 (NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1) and rrnL (large ribosomal subunit) in order to analyse genetic relatedness and evolutionary relationships.

A total of 138 worms were sequenced compromising:

- human whipworms collected from infected patients in Uganda & Ecuador,

- Trichuris spp. from non-human primates from captive baboons in USA and Denmark and from African Green monkeys at Saint Kitts,

- T. suis from experimentally infected pigs in Denmark & USA and naturally infected pigs in Uganda, Ecuador and China.

Included in the analysis were two sequences of nad1 & rrnL from the mitochondrial genomes of a human T. trichiura and a pig T. suis from China plus a partial sequence of rrnL gene of a human derived T. trichiura from China, all obtained from Genbank.

The authors found that the Trichuris parasites from humans and pigs were genetically very distinct with different demographic histories;

Phylogenetic analysis revealed that T. suis populations from Uganda and China clustered into separate clades whereas worms from Denmark and USA clustered together. The Ecuador T. suis worms were split between the Denmark/USA clade and the China clade. Human derived T. trichiura clustered into three clades based on their geographical origin (Uganda, China and Ecuador). The majority of baboon and green monkey worms clustered with T. trichiura from Uganda yet some clustered in a totally different clade which the authors referred to as the ‘Trichuris non-human primates’ clade. Further analysis of the population genetic structure of human and pig derived worms revealed that all populations were highly differentiated with the exception of T. trichiura worms from humans in Uganda, baboons and green moneys. These Trichuris populations were less differentiated, suggesting gene flow occurring between these populations of Trichuris which supports the theory of an African origin of Trichuris in primates.

The authors identified two important divergent events for both T. trichiura and T. suis. The first split for human T. trichiura occurred between the Ugandan and China/Ecuador populations (over 500,000 generations ago), then a second split between the China and Ecuador populations (120,000 generations). This again supports the theory of T. trichiura originating in Africa and spreading to Asia and South America. For T. suis, the first divergent event occurred between USA/Denmark and China/ Uganda populations about 80,000-240,000 generations ago. The second split was between China and Uganda populations (32,000-90,000 generations). The authors note how this second split in fact mirrors the demographic history of their porcine hosts, suggesting that the introduction of pigs (and their parasites) to East Africa came from the Far East thousands of years ago.

Conclusion

Hawash et al (2016) provide genetic evidence that Trichuris trichiura originated in primates in Africa. Human activity then brought it first to Asia and then on to South America. T. suis on the other hand probably evolved after a host-switching event in Asia which was then spread globally through host dispersal & human activities. For us then T. trichiura is very much an old family heirloom, whereas the poor pig has picked up a nasty souvenir in the form of T. suis.

Comments