Rivers have formed the crux of civilizations throughout history, providing a lifeline and a means of communication and trade. Rivers and waterways are the still the foci of human life all over the world from polar regions to the tropics. It is no small wonder then that insects that thrive on humans and human activity also focus their life cycles around them. Many of these insects, such as the Aedes mosquito and tsetse flies are vectors for human and animal parasites.

Dengue fever is caused by the Dengue virus and the spread of its vector, Aedes mosquitoes, in the Amazon region has, in part, been associated with vehicular transportation. The exact mechanism was unknown and so Sarah Anne Guagliardo and colleagues investigated the infestation of A. aegytpi in various vehicle types, both terrestrial and aquatic, in the Amazonian city of Iquitos, Peru.

Their results published in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases in April show that barges accounted for most of the infestations, with 71.9% of large barges being infested and 39.4 % medium barges being infested. In comparison, buses had an overall infestation rate of 12.5 %. Whether the infestation was with adult or immature (larvae and pupae) mosquitoes depended on the time of year – with adults being found most in October whilst immature mosquitoes were found mostly in February followed by October. The team also found that large barges were infested with a total of 9 mosquito species (including Aedes aegpti) native to the Iquitos region, on the other hand 15 species were found on medium barges though abundance of them was lower.

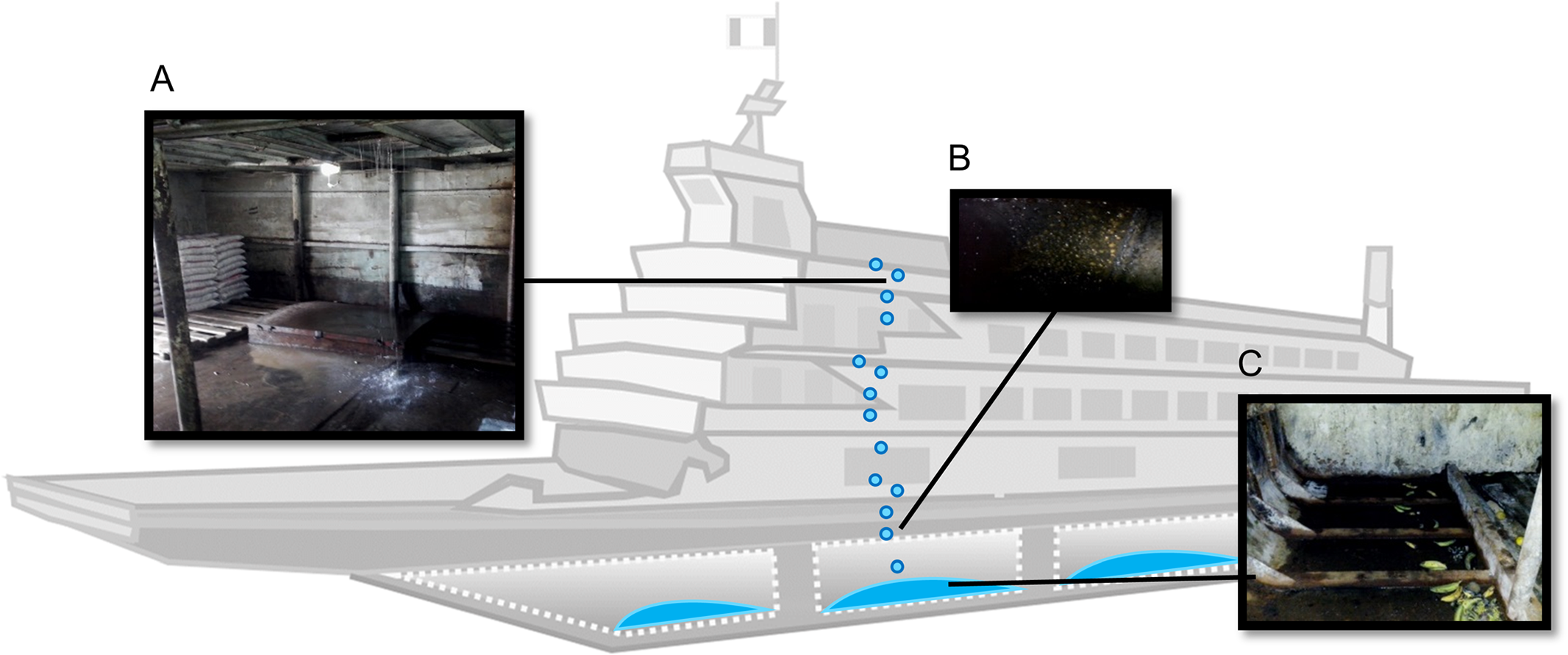

What is so special about barges in particular? Guagliado and her team found that the vast majority of infestation is in the cargo hold where puddles tend to form – an ideal breeding ground for mosquitoes. Clearly, aquatic transport is an important means of spreading the dengue vector, and to stop the spread, authorities and health agencies need to work with barge owners to reduce mosquito infestation.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic…

The tsetse fly is the vector of Trypanasoma species that cause sleeping sickness. The tsetse fly targets moving hosts and so it stands to reason that they are particularly attracted to humans traveling at speed – such as in Jeeps or boats.

But what if we can use this to our advantage? Jean-Baptiste Rayaisse and his team tested whether ‘pirogues’ or canoes can become ‘baited boats’ in an innovative way to control riverine tsetse flies. The team used baits called ‘tiny target’ that are currently being deployed in trials in Guinea and Burkino Faso in their experiments. A ‘tiny target’ has a blue polyester central panel that is flanked by black polyethylene netting. Both sides of the target are covered in a sticky insecticidal film to catch the flies.

A stationary target was deployed on the banks of the Comoe River, in the Folozo game reserve in southern Burkino Faso. At the same time, a tiny target was attached to a pirogue that traveled along the river at a speed of 1.1 m/s for 100 metres up and down the river for 2 hours. This test was conducted at two sites along the river for 14 days once in the morning and once in the afternoon. In this way, the team discovered that both the stationary and mobile targets had significantly greater number of tsetse flies in the afternoon.

For the two predominant species of tsetse fly caught in the traps – Glossina tachinoides and G. p. gambiensis – the mobile target caught a significantly larger number of flies than the stationary one. More male flies were caught in the afternoon by the stationary target, but on the mobile targets there were more male flies caught in both the morning and the afternoon. The higher number of males caught may be associated with males travelling to seek females.

As baited boats caught significantly more tsetse flies than the stationary baits, they may be a promising tool in controlling the vectors, especially in areas, such as mangroves and foliage dense rivers, where tsetse control is difficult to implement.

Rivers and waterways will continue to be important channels of travel for humans, but our transport systems are also an easy way for disease vectors, and indirectly the parasites they carry, to hitch a ride to new pastures and consequently new victims. Therefore, our transport systems should be altered so that they do not become hospitable to these hitchhikers – or even better used to control their numbers.

Comments