People are suffering severe allergic reactions (including anaphylaxis) to meat products as tick bites cause the human body to mount an immune response against the mammalian carbohydrate “alpha-gal”. This unusual condition has so far been identified in Australia and in the United States, however, the numbers of those affected is substantial and appears to be increasing.

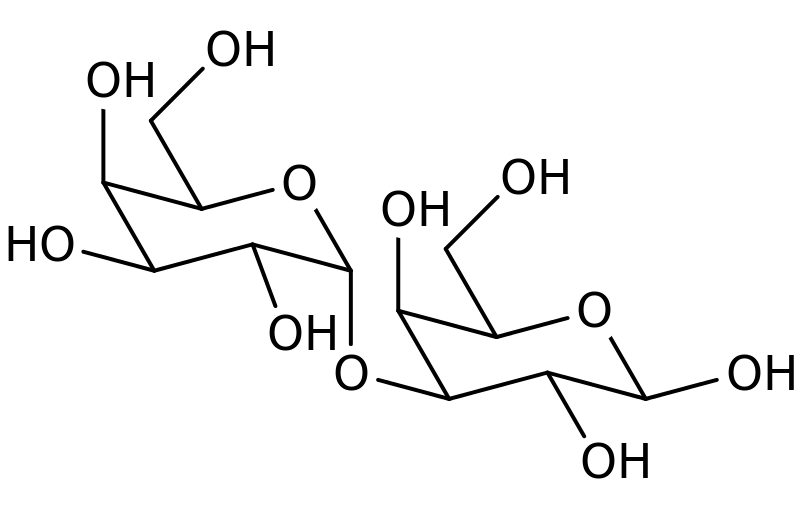

Galactose-alpha-1,3,-galactose (alpha-gal) is a carbohydrate compound readily synthesised in the mammalian body by the glycosylation enzyme alpha-1,3-galactosyltransferase. The gene responsible for producing this enzyme is inactivated in humans, apes and Old World primates and alpha-gal is not found in the human body and, as such, is seen as “foreign” by the immune system.

Although the mechanism is currently unknown, it has been suggested that ticks that previously fed on other mammals may introduce alpha-gal to the human body when people are bitten by a tick. As alpha-gal is not recognised, the human body mounts an immune response which includes the production of human IgE antibody specific for alpha-gal.

The reaction may not be instantaneous and there may be no symptoms of allergy for several months after the tick bite. Then symptoms may be mild to severe and life threatening, including angioedema (swelling), urticarial (hives) and anaphylaxis, and occurs a few hours after eating meat such a beef or pork which contains the oligosaccharide alpha-gal.

The link between tick bites and meat allergy was first identified in 2007 by Prof. Sheryl Van Nunen and colleagues at the Royal North Shore Hospital in Sydney,

Australia. They published an abstract in the Internal Medicine Journal where they describe 25 adults with positive skin prick tests and/or red-meat specific antibodies in their serum, 23 of which had previously had allergic reactions (14 with severe anaphylaxis) after eating red meat. In addition, 24/25 of these individuals had a history of being bitten by a tick.

Subsequently, in 2008, Prof. Thomas Platts-Mills and colleagues in the US found that patients treated with Cetuximab (a monoclonal antibody produced in a mouse cell line and used for the treatment of cancer) also suffered severe allergic reactions and that this was due to an IgE response to the oligosaccharide galactose-alpha-1,3,-galactose (alpha-gal) found on the murine portion of the heavy chain of Cetuximab. The study also showed that allergic reactions to Cetuximab were largely due to IgE antibodies that were already present in pre-treatment samples from these patients, thus demonstrating that Cetuximab itself was not responsible for the initial antibody response.

In addition, a number of patients with alpha-gal IgE antibodies also reported having episodes of anaphylaxis and angioedema after the ingestion of beef or pork. These findings coupled with the regional variation in the prevalence of pre-treatment IgE antibodies (between 0.6% and 20.8%) suggested that some environmental exposure (possibly tick bites) was responsible for causing the allergic reaction to alpha-gal.

The link between tick bites and allergy to alpha-gal was further supported in 2009 when the same group reported that of 24 patients who were suffering from anaphylaxis, angioedema or urticaria after the ingestion of red meat, and who also had alpha-gal specific IgE antibodies, 80% had also reported being bitten by ticks. Since the initial identification of the relationship between tick bites, alpha-gal and red meat allergy, the scale of the problem has become increasingly apparent in the US and Australia, with additional cases identified in Spain and Sweden.

Prof. Van Nunen kindly spoke to us about her perception of the problem in Australia; “I have diagnosed people with the complaint occasionally from the 1980’s, however, it has become increasingly prevalent since about 2003.

“In my practice alone, I have diagnosed over 500 patients (between 1985 and March 2014, with the great majority having presented from 2003 onwards).

“I currently diagnose an average of two people per week with the complaint.”

Therefore, the condition is relatively common in Prof. Van Nunen’s referral area and furthermore, it appears to be on the increase. In Australia, the condition is thought to be caused by the Australian paralysis tick, Ixodes holocyclus, which is found in a narrow band along the east coast. Like its European and North American counterparts (I. ricinus, I. scapularis, I. pacificus) this tick has a cosmopolitan host range that includes a variety of mammal species and, when the opportunity arises, people which can lead to the allergies observed.

The tick induced mammalian meat allergy is also a serious problem in the US, where the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum, is thought to be responsible. In excess of 1000 cases are known in Virginia alone and it estimated that over 5000 people may have the condition in the South Eastern US where the tick is present. In some cases the antibody response reduces to a level where people may be able to eat red meat again but, in many cases, people have to avoid eating red meat and are restricted to a diet where chicken and fish are the only meat products they are able to consume.

Work is ongoing to identify the exact mechanism whereby tick bites induce this allergic response and recently alpha-gal has been identified in the gastrointestinal tract of Ixodes ricinus in Sweden, suggesting a possible route of introduction. Whether the condition is simply better recognised, as a result of increased awareness and immunological testing, or whether this condition is truly on the rise, possibly as a result of local climate change, increased host abundance (e.g. deer in the US) or increased recreational activities (walking/biking) contributing to increased contact rates between ticks and humans, remains to be seen.

4 Comments