As of March 28th, 2023, with more than 57,000 people who died after a magnitude 7.8 earthquake that hit Turkey on February 6th 2023, Turkey has been left with infrastructure and facilities damage, injured and displaced refugees. Like any earthquake that reaches this magnitude, the survivors will have to cope with the series of aftershocks with magnitude varying between 7.5 and less, lasting for a longer time frame.The question that arises here is where all these survivors who have lost their home go and live again when there is no possibility to rebuild.

Instead of being viewed as a collection of shelters, refugee camps should be seen as urban settlements as they are also vulnerable to the same pressures and more. We believe that resilient emergency settlements can be a solution to most, if not all, of these pressures.

Be it earthquakes or any other natural or man-made disaster, including climatic extreme events, political conflicts, or wars, people suffer. When your home is lost, hope is a tough word. Emergency settlements are often set up to provide temporary shelter, food, and medical aid to those affected by the disaster until they can rebuild their lives. These settlements are a “Band-Aid” solution that helps to alleviate the immediate suffering of those affected by the disaster, but what if they add to the trauma by exposing communities to a new set of disasters? What if there is more conflict, more risk of natural disasters, and more probability of man-made disaster events due to the planning and design within these settlements?

On one hand, these settlements suffer from conflicts and environmental pressures and on the other hand, they also bear the inadequacies of services and facilities. This increases the refugee population’s susceptibility to climatic and environmental extremes as well as a poor quality of life.

Emergency settlements are often designed to be of a temporary nature but end up adopting a more permanent status by becoming informal settlements. In our paper published in City, Territory, and Architecture, we tried to understand one such informal settlement set up as an emergency camp, the Dalhamyie settlement in Bekaa, Lebanon. We found that these settlements are exposed to multiple risks.

External risks such as floods, storms (climate-induced disaster risk), eviction threats, and conflicts, internal risks, on the other hand, are present due to the inherent planning of the settlement itself. These include unplanned and organic growth, substandard shelters, a lack of physical and social infrastructure, a lack of a decent livelihood, and food insecurity. Just like an urban settlement, these camps also face the resultant challenges of waste disposal, water contamination, and various health hazards. The household expenditure of the refugees in the entire Bekaa valley is majorly on the food, debt repayment and the health services.

We are not proposing that these emergency settlements should be planned as cities that are there to stay permanently, but we profess the idea of resilient cities on emergency shelters to better mitigate the pressures by designing flexible structures that can be shifted or moved.

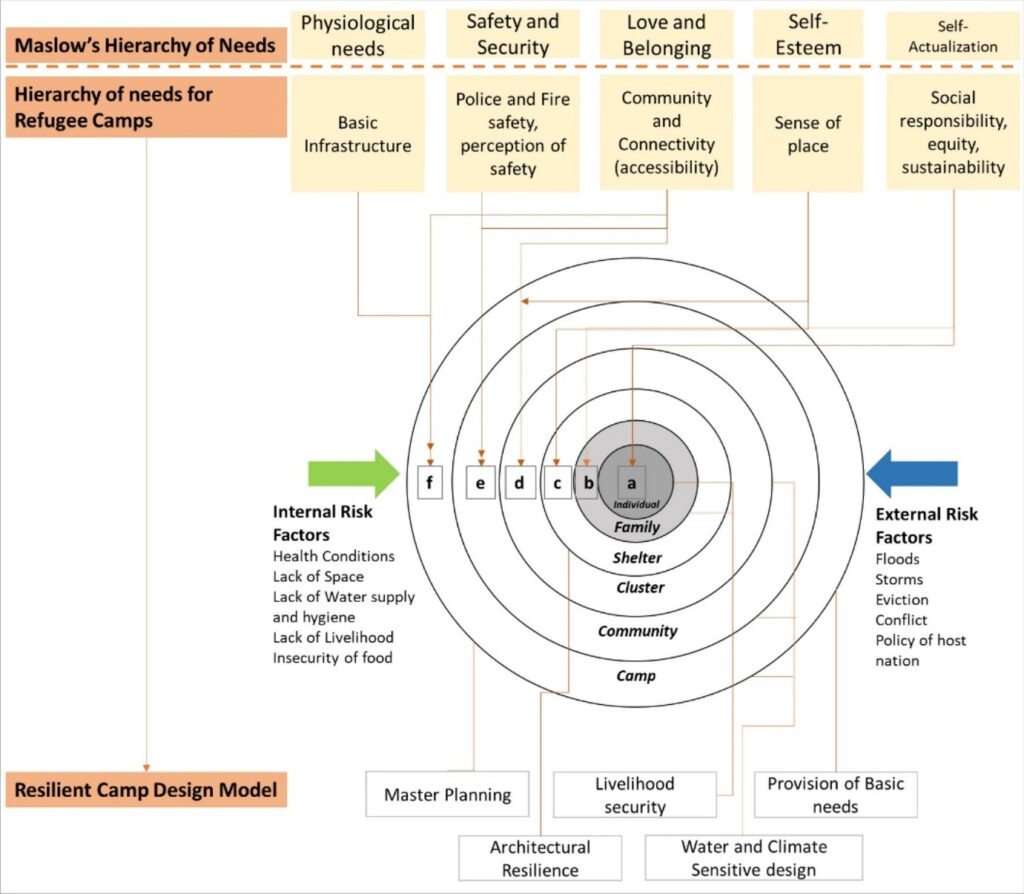

We propose a model that summarizes the key elements that need to be taken into account while analyzing all geographical, socioeconomic, and scientific (including natural hazards, resilient engineering, architecture design) aspects and factors for a sustainable and typical camp or settlement for refugees. It also demonstrates how resilience can be attained in a settlement at various scales, from the level of the individual to the level of the entire camp.

A hierarchy of needs for refugee camps can be adapted from Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which forms the foundation of human needs and aspirations. The model includes planning and design level strategies for shelter design, water supply, reuse of water, and rainwater harvesting with suitable site selection and climate considerations. It also suggests strategies for circular waste management, improving access to community toilets, sand distribution centers, as well as mechanisms to strengthen the livelihood within the camps through the recycling of waste and community and kitchen gardens that can also reduce the food insecurity and improve health conditions through appropriate nutrients intake.

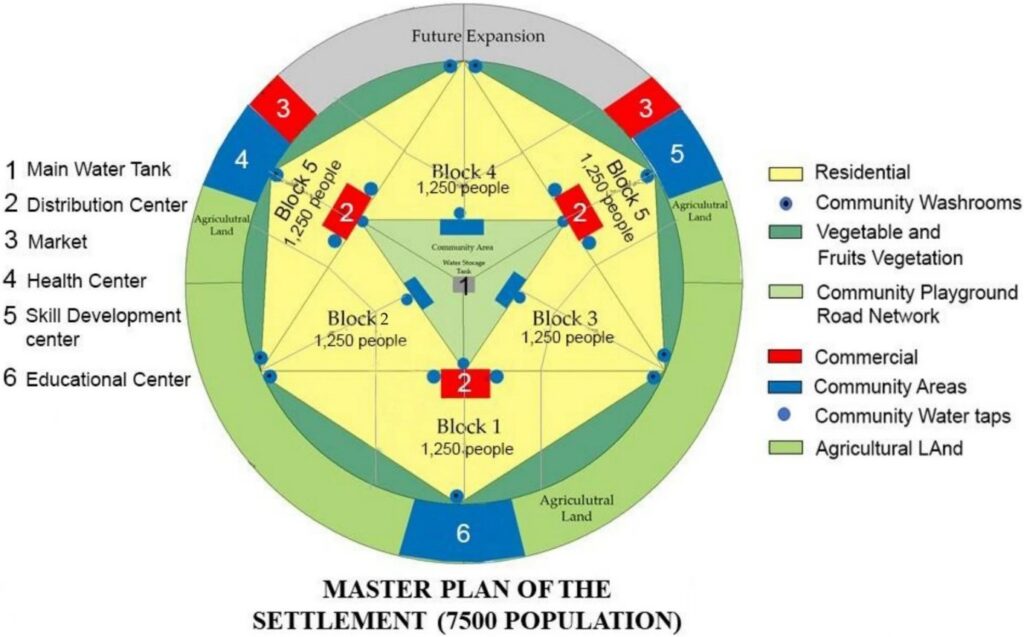

We demonstrate how this model can be adapted in a context like Dalhamyie settlement in Bekaa, Lebanon by applying the strategies through a master plan guiding the development in the camp.

The proposed resilient design model is a design umbrella strategy that can be modified and altered depending on the settlement population, site constraints and resource availability. The model addresses the challenges and multiple risks that the people are exposed to, and incorporates the context, pattern, culture, socio-economic standing and aspirations of the people.

We believe that such a model can be applied to varied contexts while planning for emergency camps and give local refugee communities a chance to achieve greater resilience and self-sustainability during crisis situations and enhance their quality of life.

About the Authors of the research

Pallavi Tiwari is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Physical Planning, School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi, India. She is also a doctoral scholar at the same institute with a research focus on environmental health risk assessment in urban planning. She holds a Masters in Planning with specialization in Urban Planning and Bachelors in Architecture.

Lübna Amir is a Professor in Earth Sciences at the University of Sciences and Technology Houari Boumediene, in Algiers, Algeria. Her research is mostly on natural disasters (earthquakes, tsunami) with a special focus on vulnerabilities and environmental issues. She holds a PhD degree on Geosciences (ULP, Nancy, France) and a Master degree on Geophysics (IPGS, Strasbourg, France).

Nibal Al Azzawi is an Architect practicing in UAE. She is a graduate architect from Architectural engineering Department University of Sharjah, Sharjah, UAE.

Comments