This blog post has been cross-posted from the SpringerOpen blog.

Woodblock printing flourished in Japan during the Edo Period (1603-1868). While Japanese woodblock prints are now in the collection of many museums and art galleries, they were not considered ‘proper art’ when they were originally produced. The price of a print was low – about a double portion of soba noodles – making them affordable for everybody.

What are woodblock prints?

Prints were made using carved woodblocks and printed according to demand. If a design was very popular, it would be printed many times, most likely until the woodblocks started falling apart due to wear. There are no records of how many times a specific design was printed. As a rough estimate, experts believe there could have been 8000 prints made of Hokusai’s “The Great Wave”, the most iconic Japanese print. Most prints didn’t survive, because they weren’t considered valuable and people therefore didn’t take care of them as much. Prints would also have been lost in fires and earthquakes, which were frequent in Japanese cities.

An evolution of colors

What is interesting about prints of the same design (i.e. prints made with the same set of woodblocks) is that the colour scheme varies. A print could be printed as an all blue landscape using subtle variations of blue, but also as a colourful image using many more colours. See the example of “Tsukudajima in Musashi Province” by Hokusai below.

How a Japanese print evolved in time is a question that intrigues art historians and collectors. In particular, it is believed that the artist who designed a print would initially choose the colours of the prints, but then the publisher (who was responsible for the commercial success of a print) would often decide to alter the colours. To better understand the vision of an artist, it is essential to identify the earliest prints. As there are no records of when a print was produced, it can be very difficult to determine whether a print is early or late.

Which came first?

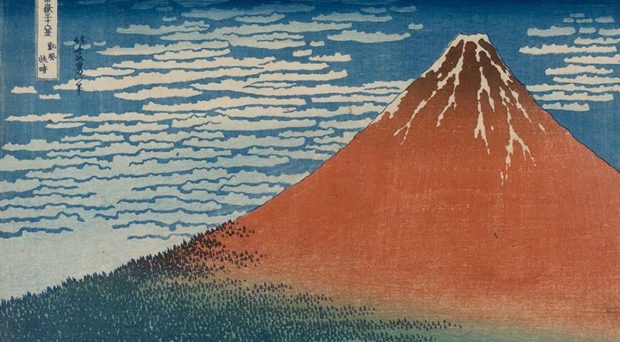

In my research, I compared two ‘Red Fuji’ prints by Hokusai made from the same set of woodblocks, but with very different colour schemes. To do so, I developed a methodology based on examining signs of woodblock wear, identifying the pigments used on the print, understanding printing techniques and studying tonal contrast. My conclusion was that the print with unusually mute colours, which is very rare, was earlier than the other print. In fact, it seems highly likely that this print, nicknamed ‘Pink Fuji’, is a first edition print. As well as showing fewer signs of woodblock wear, it used more orpiment, an expensive pigment at the time, and the colour of Mount Fuji varying from green at the bottom to dark brown at the summit was printed using a complex technique, which wouldn’t have been suitable for mass production.

Comments