People with learning disabilities might find it challenging to understand new or complex information and/or learn new skills. The experience of having a learning disability is different for every person, whereby some people may need more support throughout their life than others. Studies note that approximately 10%-25% of people with learning disabilities display aggressive challenging behavior. Therefore, they are at greater risk of restrictive practices such as inappropriate or over prescription of medication (e.g., antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers), physical restraint, seclusion, or segregation. This can result in low quality of life and an increased risk of physical harm and psychological distress for both the person with a learning disability and their carers.

What do we mean by aggressive challenging behavior?

Aggressive challenging behavior describes a broad range of behaviors that are of such intensity and frequency, they put the physical safety of the person or others at risk and restrict or limit their participation in community life. It is important to remember that people showing these behaviors most likely do not intend to harm others. Aggressive challenging behaviors usually have many reasons why they occur and relate to underlying biological differences, psychological challenges, and lack of appropriate social support.

The PETAL Program

The current approaches for addressing aggressive challenging behavior are mainly behavioral and single-component therapies (e.g., Positive Behavioral Support, anger management, cognitive-behavioral therapy) which will work for some individuals but not all.

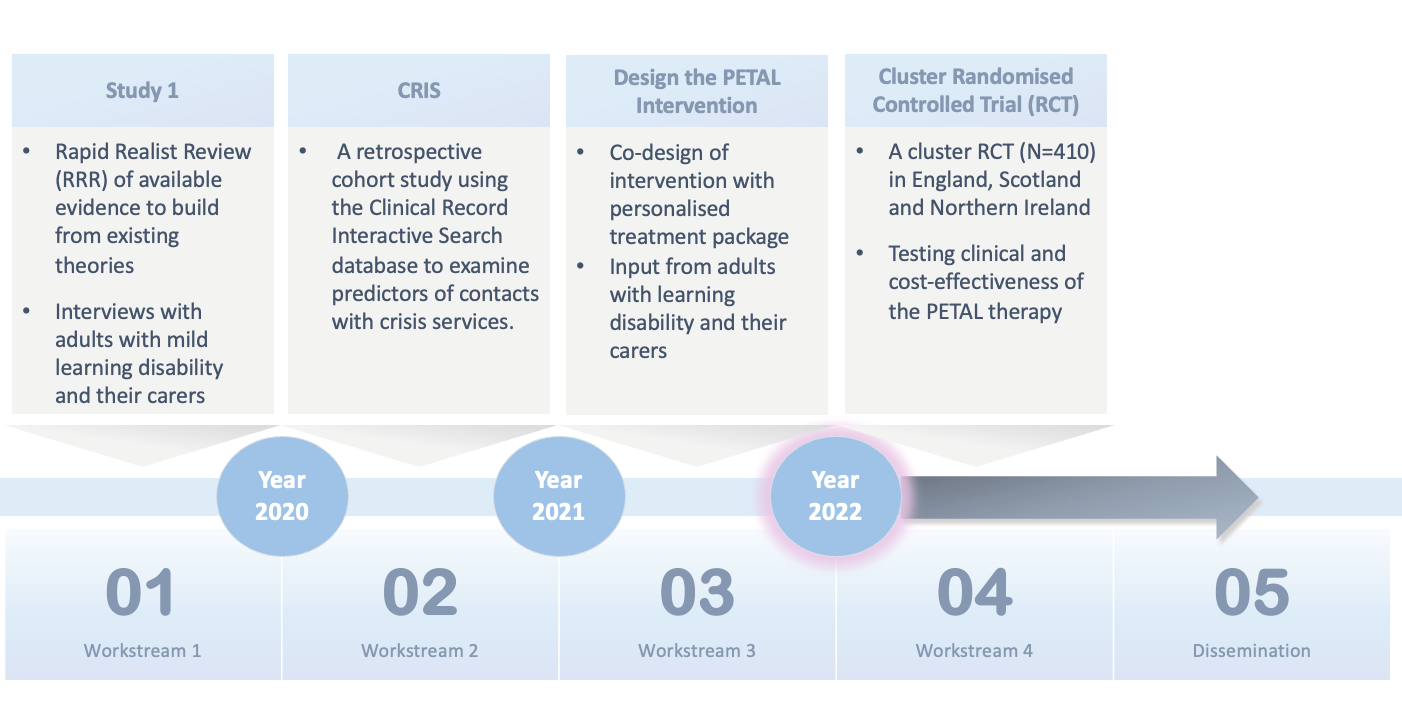

The PETAL Program is funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). It is divided into four workstreams.

In the first workstream, we looked at previous interventions for aggressive challenging behavior and developed theories to see what works, for whom and in what circumstances. We also conducted qualitative interviews to explore the facilitators and barriers to therapy outcomes.

Secondly, we looked at a mental health database to examine the profiles of adults with learning disabilities who display aggressive challenging behavior and to investigate what underpins the presentation. For example, we found associations with mood instability and increased social care needs.

During the third workstream, we developed the personalized therapy through co-production meetings with adults with learning disabilities and family carers while integrating findings from the first two workstreams above.

The PETAL therapy aims to empower people with learning disabilities and their (family or paid) carers by equipping them with new skills to better understand the display of aggressive challenging behavior, improve communication between them and prevent and/or manage more effectively aggressive incidents. The PETAL therapy is manualized and is intended to be delivered over 14 weeks with tailored session content, duration, pace, and format to suit individual abilities and needs. Adults with learning disability and their carers will also receive a workbook to help them follow the session content and to support them to complete home practice tasks in between sessions.

The fourth workstream will evaluate whether the PETAL therapy is effective at reducing aggressive challenging behavior and cost-effective test in a randomized controlled trial across England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. We will also explore how the therapy can be implemented into routine care.

Listening to experts by experience

While speaking to family carers and adults with learning disabilities they said the following:

“Remember, this is not about fixing people. It’s about giving the person a voice, influence, and control so they can enjoy a better quality of life something which we all aspire to. It is important work that could make a big difference.” (Family carer)

Our interviews highlighted the importance of listening to people with learning disabilities and how giving them space to express themselves in therapy makes them feel valued and understood. One of the people we interviewed said:

“… she understood what I was saying. She’d give examples how to help and… [she was] willing to talk about it and not just shutting it off.” (Adult with intellectual disability)

Comments