Lyme disease is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria that are transmitted through the bite of infected ticks. It is the most common vector-borne infection in the United States and Europe, with dermatologic, cardiac, neurologic, and arthritic manifestations.

About 10% of patients with Lyme arthritis fail to respond to antibiotic therapy and continue to have persistent joint inflammation. In addition, some patients report persistent symptoms of pain, fatigue, or difficulties with concentration and memory after antibiotic treatment and in the absence of evidence for ongoing infection. There is some evidence to indicate that, in a significant subset of affected individuals, these symptoms are associated with ongoing inflammatory mechanisms.

Partly due to its multisystemic nature and also because of the potential for persistence of symptoms, Lyme disease has been postulated to have a causal relationship with several chronic conditions. Because some of the proposed associations may have a significant impact on treatment or yield important clues regarding disease etiology and mechanism, their careful analysis and scrutiny can be particularly consequential. For example, published articles and on-line postings had previously speculated a strong causal link between active Lyme disease and autism, garnering considerable attention and concern. Subsequent case-control studies in 2013, however, were able to rule out the suggested association.

Lyme disease and celiac disease parallels

Another disorder with an incompletely understood etiology and a speculated link to Lyme disease is celiac disease. Celiac disease is characterized by an aberrant inflammatory response to ingested gluten in wheat and related cereals that results in tissue damage in the small intestine, while also having several systemic manifestations.

There is evidence to indicate that exposure to infectious agents may increase the risk of celiac disease.

Because celiac disease can occur at any age, factors other than genes and gluten ingestion are believed to play a role in disease onset. In fact, there is evidence to indicate that exposure to infectious agents may increase the risk of celiac disease. Recent research has pointed to a potential mechanism by which an inflammatory response triggered by infection might contribute to the development of autoimmunity in celiac disease.

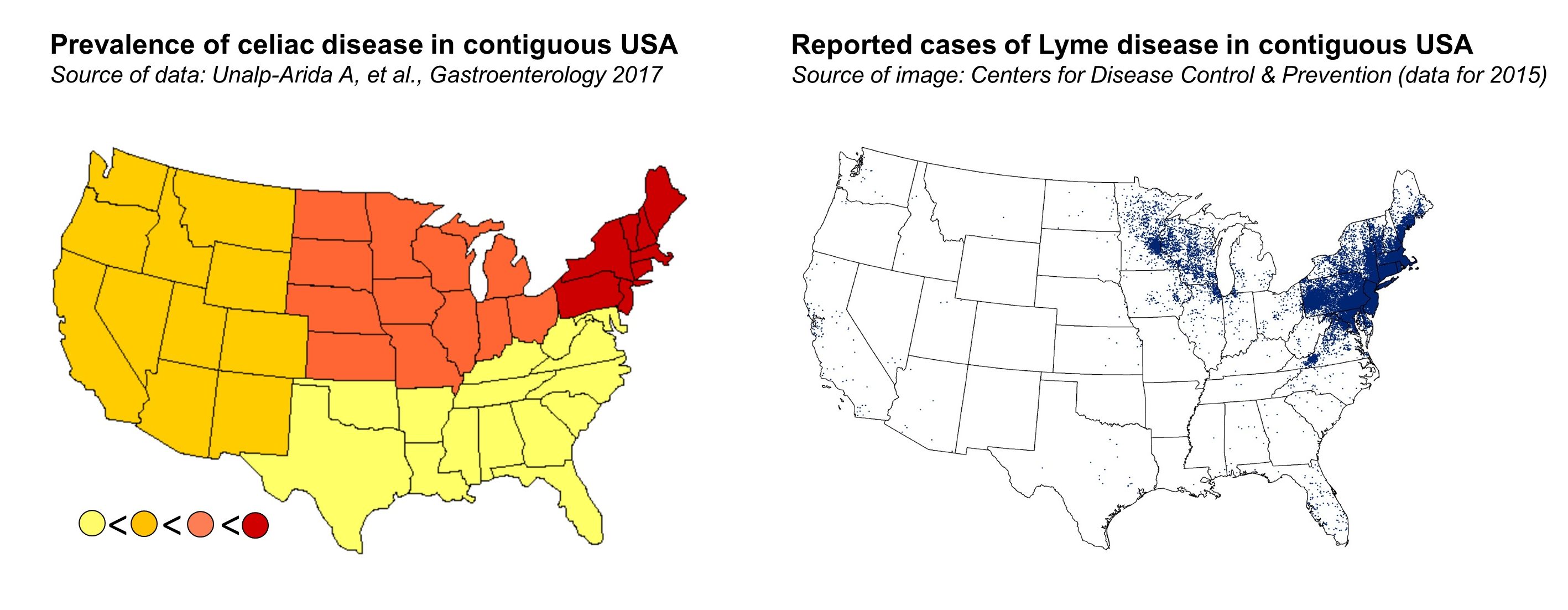

What is particularly intriguing is that both celiac disease and Lyme disease have seen a parallel steady increase in their frequencies within the past few decades. Furthermore, studies examining the regional variation in the prevalence of celiac disease have demonstrated some similarity with the geographic distribution of Lyme disease. In the United States, celiac disease has been found to be most prevalent in the Northeast and the Midwest regions, where the great majority of cases of Lyme disease also occur. All of this brings up the question of whether the occurrence of borrelia infection can increase the risk of developing celiac disease.

Investigating a possible link

We decided to tackle this question by looking at a large population of celiac disease patients and controls, totaling roughly 94,000 individuals, in Sweden. The population-based design gave the study high statistical power to detect small effects. The setting of the study was also particularly relevant, because not only does Sweden have one of the highest rates of celiac disease in the world, but the majority of its population also lives in areas where Lyme disease is endemic.

The similar modest association in both directions is likely indicative of what is referred to as surveillance bias rather than a bona fide risk.

Our initial findings indicated a slightly increased risk of celiac disease in patients who had been previously diagnosed with Lyme disease. However, upon further analysis, we found the reverse to hold true as well; that is, a similarly modest increased risk of acquiring Lyme disease after being diagnosed with celiac disease.

The similar modest association in both directions is likely indicative of what is referred to as surveillance bias rather than a bona fide risk. Here, the surveillance bias is driven by the possibility that physicians are more likely to investigate a patient presenting with Lyme disease for markers of celiac disease, and vice versa, given that there is some overlap between the systemic symptoms of the two.

This is strengthened by the fact that the risk in both directions was strongest in the initial period of follow-up after the diagnosis of either disease. In addition, of the large population of celiac disease patients included in our study, a very small proportion—less than 0.2 percent—had previously had Lyme disease, offering further evidence that Lyme disease does not represent a substantive risk factor in the development of celiac disease.

Looked at in its entirety, our data suggest that, in spite of the increasing incidence of Lyme disease, the infection does not have a causal association with celiac disease. Research into identifying the environmental factors responsible for triggering celiac disease and possibly driving the considerable recent rise in its prevalence would need to continue, focusing on other candidates. Furthermore, similarly designed future analyses can help to clarify any suspected link between Lyme disease and other chronic conditions.

Comments