Sexually transmitted Diseases (STDs) are social diseases. Treating an infected person without considering the sex partner(s) is ineffective and can lead to repeat infections and spread of these epidemics.

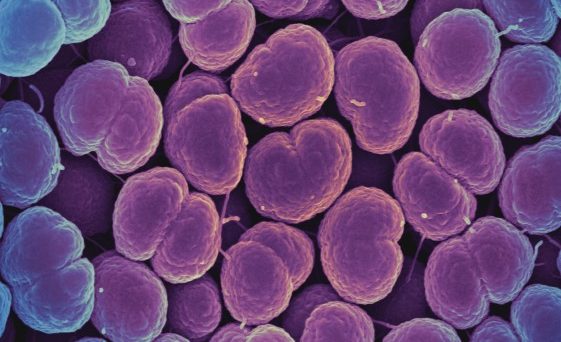

The rates of Chlamydia trachomatis infection continue to rise and the rates of gonorrhea are consistently high particularly among youth, African Americans, and those living in the southern United States. These infections are particularly problematic because they tend to be asymptomatic, so infected persons may not seek care.

The notion is that by accelerating and facilitating partner treatment, the chance of re-infection to the index person is minimized, thus reducing the effects of repeat infection

Expedited partner therapy (EPT) is the provision of medicine to a sex partner of a persons infected with an STD without the requirement of a clinical exam. The notion is that by accelerating and facilitating partner treatment, the chance of re-infection to the index person is minimized, thus reducing the effects of repeat infection (such as pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, and increased HIV risk). Also reducing STDs can reduce the chances of getting HIV.

EPT was endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2006 as a useful option for partner management for selected STDs among heterosexuals. To date, at least 26 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted to evaluate EPT.

A recent meta-analysis of these RCTs found that EPT reduced repeat infections by 20-29% depending on the STD and the demographics of the index person and resulted in more partners being treated when compared to standard partner referral by the index patient. So there is good evidence that, in randomized trials and among heterosexuals, EPT is efficacious for reducing repeat STIs.

Despite the evidence for EPT and the decade old endorsement by CDC, it is often not used. Reasons for low usage are many including fear of liability by providers and institutions, and lack of clarity on who will pay for the partner treatment. EPT is legal in most states, but insurance providers are reluctant to pay for persons who are not in their network. If offered, patients are likely to take it for their long-term partners and these partners are likely to accept the treatment.

So payment and policy are needed for EPT to really be accessible to infected persons, who in the case of chlamydia and gonorrhea, tend to be youth and racial minorities.

EPT has not been recommended by CDC for use among gay and bisexual men because of the fear that these individuals would not seek full reproductive care, including HIV testing. While this is an important consideration, the reality is that approximately 20-40% of partners of infected persons actually do seek care and EPT could increase the percentage getting care.

The pilot study by Clark et al. of Expedited Partner Therapy among gay and bisexual men in Peru is an important step in evaluating the benefit of EPT in this population.

The pilot study by Clark et al. of EPT among gay and bisexual men in Peru is an important step in evaluating the benefit of EPT in this population. The study demonstrated that EPT is feasible for this group and resulted in high rates of partner notification (> 80%). If the EPT was accompanied by materials promoting the partner to take the EPT and then seek full reproductive health care including an HIV test, EPT could serve as an effective outreach intervention.

EPT is an important intervention to improve access to care and could lead to a reduction in the intense health disparity that is seen with STDs. It can reduce reproductive health problems and may reduce the spread of infection in the community. It is imperative that providers are educated, policy for payment is enacted, and more translational research is conducted to bring this evidence-based intervention to practice for all persons with STDs.

Comments