Drug development is a costly business. The exact costs are debatable, but an average estimate of a billion dollars per drug is not far off the mark. On the other hand there are large profits to be made. For example, in 2014 the top 50 selling pharmaceutical products had global sales of a minimum of $2 billion each, and the top 10 ranged from $6.6 to $13 billion.

It is not therefore surprising that drug companies are reluctant to withdraw successful products from the market, even when they turn out to cause serious adverse reactions.

We have previously reported a study of 462 medicines that were withdrawn from the market because of adverse drug reactions discovered after marketing. We found that adverse reactions leading to drug withdrawals are being discovered quicker than before after marketing, but drugs that are eventually withdrawn are not being withdrawn more quickly after the identification of the first reported adverse reactions. This is so even when it is deaths that prompt drug withdrawals.

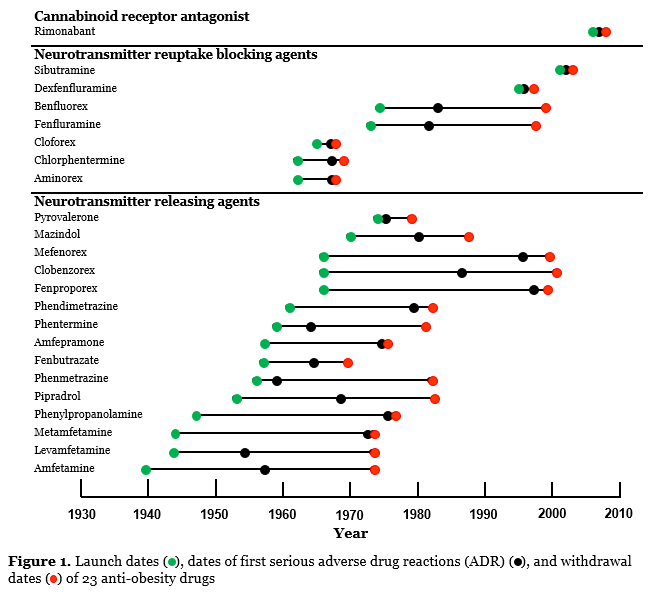

We have now investigated the patterns of withdrawal of 25 anti-obesity drugs that caused serious adverse reactions and that were consequently withdrawn from the market between 1964 and 2009; 23 of these had mechanisms of actions via altered central monoamine neurotransmitter or brain receptor function (Figure 1). Psychiatric disturbances, cardiac toxicity (mainly attributable to monoamine neurotransmitter reuptake inhibitors), and drug abuse or dependence (mainly attributable to neurotransmitter releasing agents) together accounted for 83% of withdrawals. Deaths were reportedly associated with seven products (28%).

In a separate unpublished analysis of the reported benefits and harms in pivotal trials that were used to justify the licensing of some of these drugs, we have found that whilst these medicines benefit weight loss, the effects are relatively small. Serious harms were detected at some time after marketing, and were usually not discovered in the pivotal trials.

These findings suggest that regulatory agencies should be circumspect when considering whether to license new centrally-acting drugs for weight loss. The evidence about withdrawals of previously marketed medicines suggests that drug companies have profited, but patients who have suffered severe adverse reactions have ultimately lost.

Comments