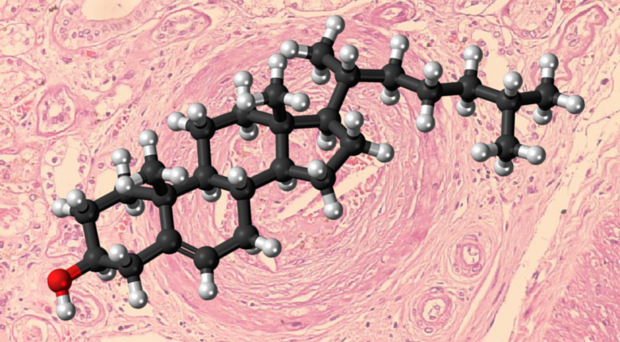

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide. Among well-known risk factors, such as smoking, hypertension, age, gender, diabetes, and so on, levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), the ‘bad’ cholesterol, are very strong predictors of CVD events and death.

Low-density lipoprotein as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease

We are born with very low LDL cholesterol levels (about 30 mg/dL), but as we grow up these levels increase. Of note, this increase is more pronounced in western societies (LDL cholesterol reaching a mean level of about 130 mg/dL), whereas in primitives does not exceed 70 mg/dL. Needless to say that CVD is almost unknown in the latter societies.

People born with high LDL cholesterol levels due to a common genetic disease (such as familial hypercholesterolemia) usually experience heart attack in their 20s, 30s or 40s. In contrast, those born with low LDL cholesterol levels due to genetic mutations are protected against CVD and live longer.

Current treatments for elevated LDL cholesterol

It follows that reduction of elevated LDL cholesterol levels is needed to reduce the burden of CVD. Statins are the cornerstone of cholesterol-lowering treatment. These remarkable drugs have dramatically reduced CVD events in the last 25 years.

Statins have a very good safety profile and are well tolerated by most patients. However, some patients (about 5%) experience muscle pain and there is a small but worrisome increase in the onset of new diabetes.

If a statin is not enough, then ezetimibe, a cholesterol absorption inhibitor, can be added. Recently, ezetimibe was shown to further decrease CVD events when added to a statin in patients with a recent heart attack.

Despite having powerful statins and ezetimibe there are clear unmet needs in cholesterol lowering:

- Patients who cannot tolerate statins due to side effects, especially muscle pain

- Patients with very high levels of LDL cholesterol due to familial hypercholesterolemia

- High-risk patients who cannot achieve LDL cholesterol therapeutic targets despite being on appropriate treatment.

An unanswered question is which is the real cardioprotective level of LDL cholesterol? Especially for patients with a history of heart attack or stroke: is it the 70 mg/dL that is currently recommended or should we go down to infantile levels of 40 or 30 mg/dL?

It is clear that we need new ways to lower LDL cholesterol in clinical practice. Statins and ezetimibe do so by up-regulating the receptors that pick up LDL particles and remove them from the circulation, leading them into the liver cells for destruction. The more efficiently these LDL receptors work, the less LDL circulates and less fat accumulates in our vessels.

PCSK9 is a ‘bad’ protein because it leads LDL receptors to break down and the levels of LDL cholesterol to go up.

Introducing anti-PCSK9

During the last ten years we learnt that there is a third player in the interaction of LDL particles and LDL receptors on the surface of liver cells, namely the PCSK9 protein. It is excreted by the liver cells and sticks to the LDL particle-LDL receptor complex.

In the presence of PCSK9, the LDL receptor cannot dissociate inside the liver cell and go back to the surface to bring more LDL particles inside. Instead it is destroyed together with the LDL particles. Therefore, PCSK9 is a ‘bad’ protein because it leads LDL receptors to break down and the levels of LDL cholesterol to go up.

How could we block PCSK9? The most appropriate way up to now is by monoclonal antibodies. These are sophisticated; selective antibodies administered by subcutaneous injections every 15 or 30 days.

These antibodies block PCSK9 and thus allow LDL receptors to survive. Two of these antibodies are at advanced development and are expected to be approved by mid-2015 in both Europe and US: evolocumab (Repatha®, Amgen) and alirocumab (Praluent®, Sanofi/Regeneron).

What are the key findings from the research published in BMC Medicine ?

A study-level meta-analysis of all anti-PCSK9 inhibitor randomized controlled studies (n=25) is published by Zhang X-L et al. This is actually the second meta-analysis of all anti-PCSK9 inhibitor studies and includes a large number of patients (n=12,200).

Both alirocumab and evolocumab lowered LDL cholesterol by more than 50% compared with a placebo. What is impressing is that these reductions came on top of statin treatment.

What is more impressing is that except from an anticipated increase in mild injection site reactions, no other excess in side effects was seen with these new drugs. Despite the short duration, a significant decrease in the rate of death was seen in the alirocumab studies.

These results are in line with the first meta-analysis published in the Annals of Internal Medicine by Navarese EP et al. Here, a significant decrease of death rate and myocardial infarction was noticed for both drugs with no increase in serious adverse events.

Analysis of CVD events of long-term studies of both alirocumab and evolocumab published very recently in the New England Journal of Medicine also showed a significant reduction with these drugs.

Of course one should keep in mind that these studies tested efficacy and safety and were not CVD outcome trials. Such trials are underway and results are anticipated in 2017. Also, the duration of these studies was short (up to a year and a half).

We are all very excited to live the revolution that these new therapies bring to CVD prevention.

The future of anti-PCSK9

Anti-PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies seem a very promising new therapeutic strategy for LDL cholesterol lowering and will soon be granted approval. They will be most useful for statin-intolerant patients, familial hypercholesterolemia individuals and high-risk patients not reaching current goals of LDL lowering.

But what if we see that reaching LDL cholesterol of 40 mg/dL further drastically reduces CVD events in patients with heart-attack? Should they be given to every such patient? And who is going to cover the high cost associated with these new agents?

These are the questions that should be addressed in the next two years. Meanwhile we are all very excited to live the revolution that these new therapies bring to CVD prevention.

One Comment