The Mediterranean diet has been linked to many health benefits, from improved longevity to reduced incidence of cardiovascular disease, cancer and depression. However, while the positive impact of this dietary pattern is well-documented (see our previous blog), a number of unanswered questions and unresolved controversies remain.

health benefits, from improved longevity to reduced incidence of cardiovascular disease, cancer and depression. However, while the positive impact of this dietary pattern is well-documented (see our previous blog), a number of unanswered questions and unresolved controversies remain.

As editors at BMC Medicine, we have encountered differences in opinion during the review and publication process of studies investigating the link between diet and health, with authors and reviewers raising pertinent questions such as:

Should alcohol and dairy products be included in the definition of the Mediterranean diet?

Can the Mediterranean diet be applied to non-Western settings?

How can we measure adherence to this dietary pattern?

To explore these open questions, we invited clinicians and researchers across the globe with an interest in diet and health to contribute to a forum article. We asked the authors to outline what the Mediterranean diet means to them, why disparities exist in the definition, and how we can study the health benefits.

What does the Mediterranean diet mean?

Kicking off the discussion in our forum article and accompanying podcast in Biome magazine, Antonia Trichopoulou from the University of Athens in Greece outlines how the Mediterranean diet can be considered a largely, but not exclusively, plant-based diet.

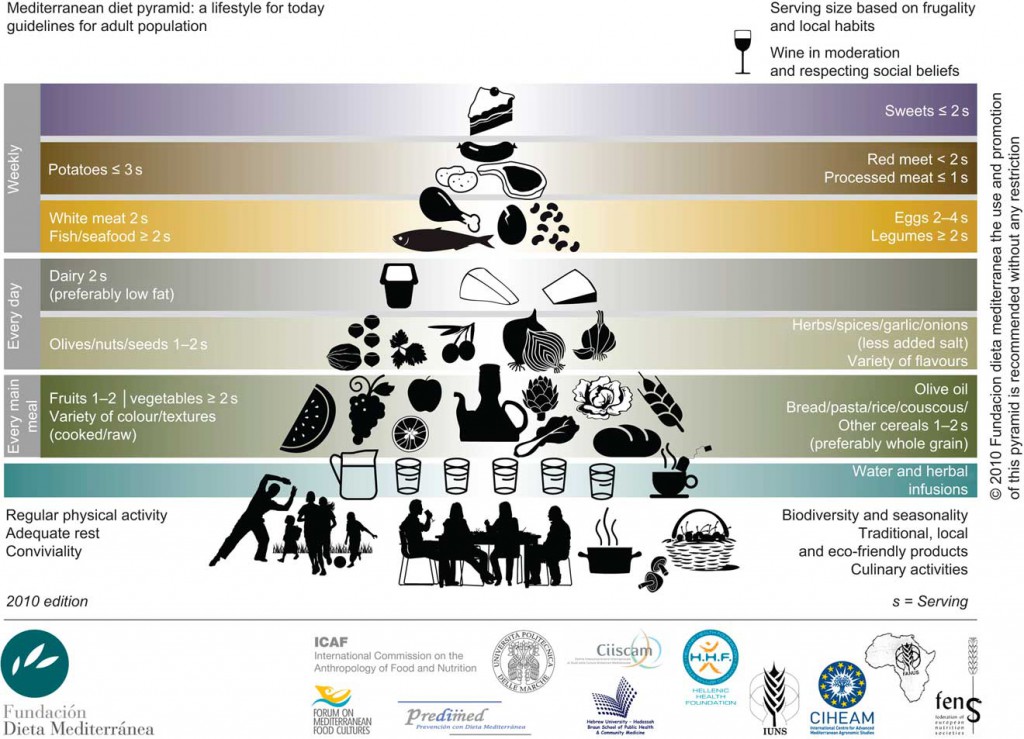

Tammy Tong and Nita Forouhi from the University of Cambridge, UK, describe the Mediterranean diet pyramid, recommended by the Fundación Dieta Mediterránea, which promotes a high consumption of fruit, vegetables and cereals, low consumption of red meats, and moderate consumption of dairy, poultry and fish.

o

Trichopoulou emphasizes that alcohol should be included in the definition of the Mediterranean diet, but should be limited to wine consumption during meals.

What disparities exist in the definition?

The main disparities in the definition of the Mediterranean diet, as highlighted by Miguel Martínez-González from the University of Navarra in Spain, concern the total amount and type of fat that should be consumed, whether low-fat dairy products should be included, and whether cereal  consumption should be limited to wholegrains. Michel de Lorgeril from Université Joseph Fourier, France, highlights that wheat is considered a major component of the Mediterranean diet in the 21st century, and alternatives to gluten-rich grains should be recommended for those with gluten sensitivity conditions such as celiac disease.

consumption should be limited to wholegrains. Michel de Lorgeril from Université Joseph Fourier, France, highlights that wheat is considered a major component of the Mediterranean diet in the 21st century, and alternatives to gluten-rich grains should be recommended for those with gluten sensitivity conditions such as celiac disease.

An important open question is why these disparities exist in the definition of the Mediterranean diet. Martínez-González explains that the reasons are complex and poorly understood, but disparities could occur because different investigations have focused on distinct components of the Mediterranean diet.

For example, the landmark Lyon Diet Heart study carried out by de Lorgeril and colleagues in the 1990s suggested that alpha-linolenic acid could be conferring the benefits, whereas the 2013 PREDIMED study identified extra-virgin olive oil as the protective factor against cardiovascular disease.

Scores to measure Mediterranean diet adherence in epidemiological and interventional studies have been developed, as summarized by Martínez-González, and such scores should facilitate a more standardized measure of Mediterranean diet adherence in future studies.

How can this dietary pattern be applied in non-Mediterranean settings?

While the Mediterranean diet is traditionally prevalent in olive-growing countries in the Mediterranean basin, its influence is increasingly spreading across the globe.

Shweta Khandelwal and Dorairaj Prabhakaran from the Public Health Foundation of India describe how a typical Indian diet compares with the Mediterranean dietary pattern in our forum article, emphasizing that some cooking oils used in India, such as mustard oil, may confer a cardioprotective effect similar to that seen with olive oil. The authors emphasize that interventional studies to assess the effects of a Mediterranean-type diet on cardiovascular risk are required in the Indian setting, and resources are required to strengthen the nutrition research infrastructure to carry out such studies.

In light of recent findings suggesting that the effect of the Mediterranean diet on cognitive decline could differ across races, it is important to establish its impact across diverse geographical settings.

How can we make our diet more ‘Mediterranean’?

With the ever-expanding body of evidence on the benefits of the Mediterranean diet and which components may confer its effects, it is important that these results are translated into effective dietary guidance.

Dariush Mozaffarian from Tufts University, United States, highlights that we should focus on positive dietary guidance – i.e. what should be consumed – rather than what should be avoided. In the Biome podcast, Mozaffarian proposes that we can move towards eating a healthy diet by picking specific goals such as increasing fruit intake to three servings a day and keeping track of progress, recommending that:

“One step at a time, one can change their diet from the traditional western, highly processed and packaged food diet toward a healthier Mediterranean diet”

You can read more about the definitions, controversies and health benefits associated with the Mediterranean diet in our forum article at https://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/12/112, and listen to our podcast featuring Miguel Martínez-González, Antonia Trichopoulou and Dariush Mozaffarian at https://www.biomedcentral.com/biome/a-mediterranean-diet-the-key-to-healthy-living/

This forum article is part of the cross-journal collection, Metabolism, diet and disease, which is published in collaboration with our sister journal BMC Biology, and remains open for submissions.

BMC Medicine: passionate about quality, transparency and clinical impact

BMC Medicine: passionate about quality, transparency and clinical impact

2013 median turnover times: initial decision three days; decision after peer review 51 days

One Comment