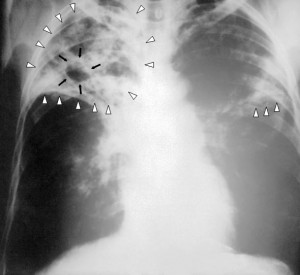

Recent estimates suggest that childhood tuberculosis (TB) rates are much higher than previously reported. The predictions, carried out by researchers at the University of Sheffield, Imperial College London and the Global Alliance for TB Drug Development, took bacterial behavior and adult infection rates into account across 22 countries with the highest incidence of TB, and suggest that more than 650,000 children develop TB each year. This figure is around 25% higher than current World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, suggesting that health officials may be missing a great opportunity to prevent the spread of infection. Leading the research, Peter Dodd highlighted that:

tuberculosis (TB) rates are much higher than previously reported. The predictions, carried out by researchers at the University of Sheffield, Imperial College London and the Global Alliance for TB Drug Development, took bacterial behavior and adult infection rates into account across 22 countries with the highest incidence of TB, and suggest that more than 650,000 children develop TB each year. This figure is around 25% higher than current World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, suggesting that health officials may be missing a great opportunity to prevent the spread of infection. Leading the research, Peter Dodd highlighted that:

“Children are an often ignored but important part of TB control efforts…our findings highlight an enormous opportunity for preventative antibiotic treatment among children who are living in the same household as an adult with infectious TB.”

Improving early TB detection in children

TB is a contagious infection mainly affecting the lungs, and can usually be cured with antibiotic treatment. Early identification of the infection is therefore important to ensure prompt, effective therapy and prevent its spread to others. However, TB can be difficult to detect in children as they harbor fewer bacteria than adults and sample collection can be difficult.

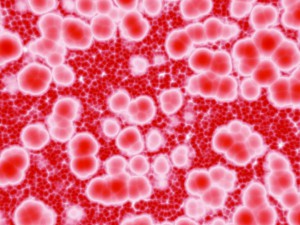

A study published in BMC Medicine by Vivek Naranbhai and colleagues has revealed that in South African children, alterations in the amount of different types of white blood cell can help to identify infants at risk of TB infection. The authors showed that an increased ratio of blood monocytes to lymphocytes is associated with higher TB risk in the first two years of life, suggesting that the monocyte:lymphocyte ratio could be used to help identify at-risk infants and prioritize them for TB testing. Naranbhai indicates that:

A study published in BMC Medicine by Vivek Naranbhai and colleagues has revealed that in South African children, alterations in the amount of different types of white blood cell can help to identify infants at risk of TB infection. The authors showed that an increased ratio of blood monocytes to lymphocytes is associated with higher TB risk in the first two years of life, suggesting that the monocyte:lymphocyte ratio could be used to help identify at-risk infants and prioritize them for TB testing. Naranbhai indicates that:

“The recent findings demonstrate how TB in children remains a hidden epidemic…our finding suggests that a measure derived from routinely conducted full blood counts, a test available in most settings, may help to identify these children as early as three months and before they develop disease. I am encouraged by the consistency of the findings across children and adults, humans and animals, in vivo and in vitro”

Identifying TB complications

Whilst the majority of TB infections are treated effectively, the disease can be fatal without treatment, and can cause complications if it spreads from the lungs to other parts of the body. One such complication is tuberculous pericarditis (TBP), which causes swelling of the tissue surrounding the heart. Pericarditis has a number of possible causes, and it can be difficult to diagnose TB as the causative pathogen in TBP cases, making treatment challenging. In a research article published in BMC Medicine, Bongani Mayosi and colleagues from Cape Town University and the University of Oxford analyzed the diagnostic accuracy of several tests for the identification of TBP. The authors demonstrated that the unstimulated interferon-gamma test is more accurate than adenosine deaminase and Xpert MTB/RIF assays for TBP detection, concluding that the test should be considered for implementation in clinical practice.

disease can be fatal without treatment, and can cause complications if it spreads from the lungs to other parts of the body. One such complication is tuberculous pericarditis (TBP), which causes swelling of the tissue surrounding the heart. Pericarditis has a number of possible causes, and it can be difficult to diagnose TB as the causative pathogen in TBP cases, making treatment challenging. In a research article published in BMC Medicine, Bongani Mayosi and colleagues from Cape Town University and the University of Oxford analyzed the diagnostic accuracy of several tests for the identification of TBP. The authors demonstrated that the unstimulated interferon-gamma test is more accurate than adenosine deaminase and Xpert MTB/RIF assays for TBP detection, concluding that the test should be considered for implementation in clinical practice.

Together, these research articles highlight the urgent need for prompt detection of TB and its complications, and suggest that sensitive tests such as unstimulated interferon-gamma could aid in the diagnosis and effective treatment of TBP. We hope that ongoing research following the study by Naranbhai and colleagues will aid in the worldwide fight against TB by facilitating early detection and prevention of disease transmission, in steps towards the global goal of zero TB deaths in children.

BMC Medicine has published a number of articles across the spectrum of TB diagnosis, control and comorbidities, which can be seen at https://www.biomedcentral.com/bmcmed/tags/TB, and Stephen Lawn explains how the Xpert MTB/RIF assay works in our video Q&A at https://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/11/158

BMC Medicine: passionate about quality, transparency and clinical impact

BMC Medicine: passionate about quality, transparency and clinical impact

2013 median turnover times: initial decision three days; decision after peer review 51 days

Comments