The first post in this series covered what you should think about when you decide whether or not to accept an invitation to peer review. This post will cover how to begin your assessment of the manuscript.

Once you‘ve accepted the invitation, the clock starts ticking and you have a set amount of time to return your report. You’ll receive the full manuscript and any additional files, and it’s tempting to just start reading and critiquing.

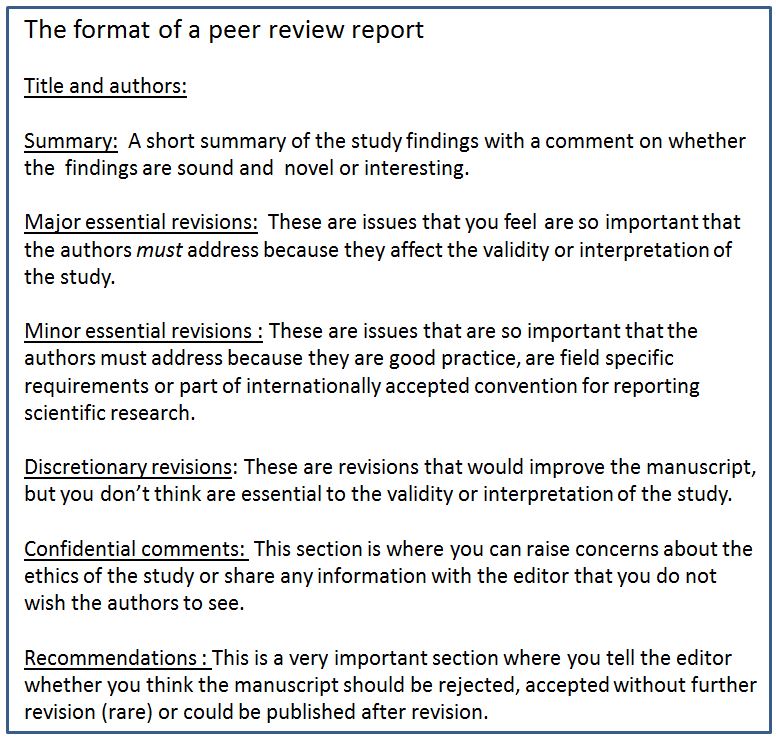

But before you dive in, remind yourself of what format your report should take. If the editor gave you a list of questions, keep these in mind. If not, it’s likely you’ll be expected to return a report as shown below:

Your initial assessment

Unless it’s an exceptionally well-written manuscript, it’s unlikely you’ll be able to write a comprehensive peer review report after just one reading. You may need to read the manuscript through at least two or three times, and go back to various sections again.

On your first reading, try to remember the following…

Is the manuscript written in an understandable way?

The Editor wants readers to be able to understand the contents. If you don’t understand it, other readers won’t either. It’s also not possible to assess the science if you don’t understand what the authors did and why.

Additionally, authors might purposefully use flamboyant or needlessly complicated language to hide deficiencies in their study. Sometimes this is because they have a competing interest – so make sure to look out for this. There will be more about competing interests in a later post.

Is all the relevant information available to you?

There are guidelines for authors for some types of study (particularly those involving human and animal research) on how their study should be reported. These guidelines are available on the EQUATOR network.

You should use the relevant reporting guideline from EQUATOR to help you peer review a manuscript. Check whether the authors have provided the information required. If they haven’t, then they haven’t provided enough information for you to review properly. You should flag this to the authors and editor, as important information has been omitted.

If there are no reporting guidelines for the type of study you are reviewing then think about whether the authors have provided enough detail to allow other researchers to repeat the study.

Once you’ve considered the clarity and completeness of the reporting, you can decide whether you do indeed have enough understandable information to proceed with a more detailed review. If not, don’t struggle to make sense of the manuscript. Send your comments back to the editor at this stage.

If the information is there, you can proceed to looking through the manuscript in more detail.

Closer scrutiny

As an expert reviewer, the editor relies on your scrutiny of the manuscript to spot flaws that would prevent publication.

The editor relies on your scrutiny of the manuscript to spot flaws that would prevent publication.

Regardless of the field, specialty or design of the study, all sound research should have some sort of logical reasoning to it. Below are the questions you should keep in mind as you peer review.

The key questions to ask

Background:

- Is there an aim, research question or reason for doing the research, and has this research been put in the context of previous work?

Methods:

- Is the study design appropriate for the study aim, research question, or reason for doing the research?

- Has the study been conducted with the appropriate materials or participants?

- Have appropriate methods been used and variables been measured?

- Is there a need for a control? Has an appropriate control been used?

- Have appropriate statistical tests been used?

Results:

- Have the results been presented clearly and completely?

- Do the results presented match the methods described?

- Are there any results missing?

- Do the results support the authors’ conclusions?

Have the authors made exaggerated claims that are not supported by their findings or put a ‘spin’ on the way they discuss their results to suit a particular point of view? This is where you should reconsider the competing interests and funding.

REMEMBER:

– Refer to the journal’s editorial policies: these explain the standards authors are required to meet, so refer to the relevant parts before you start.

– Look at the figures, tables and additional files. Look at them with the same care and attention you would the main text. Do they make sense? Are they fully explained? Do they support the authors’ conclusions?

– If you don’t feel qualified to judge the statistics then tell the Editor. They may need to use a specialist statistical reviewer.

Other factors to consider

- If the study involves human or animal participants, have the correct approvals, permissions and consents been obtained? Check the journal’s editorial policies if you are not sure what these should be.

- Do you have any concerns about the ethics of the study?

- If there are competing interests, do you think the authors have been objective in their interpretation of the results?

- Have the authors complied with any specific requirements of your field, for example data deposition?

- Have the authors provided appropriate references?

By now you should have all the information you need to advise the editor.

Look out for the next blog in this series, which will cover how to write a useful peer review report.

One Comment