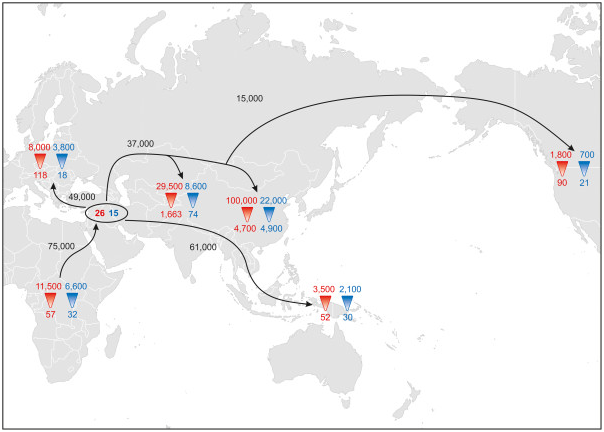

Figure 1: Women as a share of total

science researchers in 2007 or latest available year. Calculations based on

head counts (HC) of full-time equivalents (FTEs).

Shocking statistics,

recently released by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), have uncovered a grossly under-developed

scientific resource lying in abundance within the arms of each low-income

nation: the brain power of their women. Of the world’s total science

researchers, UNESCO estimates that only 27 per cent are female.

To put these statistics into context, 14.8

per cent of all researchers in India are female, falling far behind the 33.9

per cent of female researchers boasted by Europe. Male scientists outnumber

their female colleagues by more than two

to one in both Chile and Mexico, and the same is true for most countries in

Africa. Only 5.8 per cent of researchers in Guinea are women, making it the country

that experiences the most gender inequality in the field of science within

Africa.

This is not to say

that women play no significant roles in the individual domestic science

landscape of their countries. Two African countries — Lesotho (55.7 per

cent) and Cape Verde (52.3 per cent) — have achieved

gender parity for science researchers. Similarly, in Latin America and

the Caribbean women make up 45 per cent of the scientific workforce and in

Myanmar, colloquially known as Burma, the figure is reported to be as high as 85.5 per cent, well above the European average.

However, the impact that

women could have on science, particularly within developing countries, is not

yet fully explored. In general a lot of work is needed to encourage women to

advance careers in science as illustrated by the map above. SciDev, the Science and Development

Network, has acknowledged: ‘improving

girls’ access to basic and secondary education — especially in science — is

crucial’.

Open access publishing removes restrictive subscription

fees, subsequently challenging the geographical inequality experienced with

access to and use of high-quality scientific resources facilitating global

social and scientific development. However access alone is not enough. In order

to achieve gender equality within the global scientific community up-to-date

teaching methods across classrooms are essential to prevent girls from turning

away from scientific fields.

Comments