Emergency hospital admissions are rising and, increasingly, policy-makers, clinicians, and patients are worried about their effect on cancellations of elective procedures, prolonged waiting times, in-hospital infection rates, and costs. However, identifying useful strategies for reducing admissions has proved problematic; interventions designed to reduce hospitalizations often achieve no real-world benefit, yet consume scarce health resources.

Our study aimed to identify and prioritize medications that have been shown in systematic reviews to prevent patients from requiring emergency hospital care.

One promising intervention that has received little attention is medications; those which help a patient to avoid hospitalization represent high-value activity in a patient’s overall care. Medications can reduce admission rates by preventing illnesses, and mitigating symptoms or exacerbations that would have otherwise required urgent health care.

Our study in BMC Medicine, therefore, aimed to identify and prioritize medications that have been shown in systematic reviews to prevent patients from requiring emergency hospital care.

What did we do?

We searched for systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials in adults that reported hospital admissions as an outcome. The quality of evidence was assessed using GRADE criteria. Effective medications with high or moderate quality evidence were cross-referenced with UK, USA, and European clinical guidelines to determine which had an acceptable overall balance of benefit to harm.

What did we find?

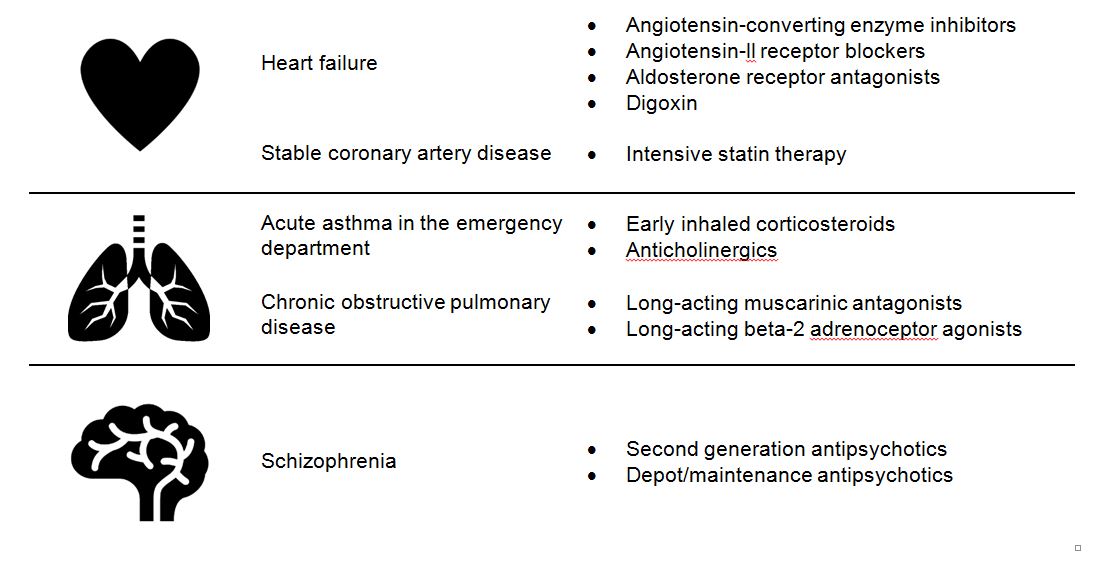

We found 140 systematic reviews, including 1,968 randomized controlled trials and 925,364 patients. We identified eleven medications that significantly reduced emergency hospital admissions; these were supported by high or moderate quality evidence, and were endorsed in clinical guidelines.

What does this mean?

Using the eleven medications that we identified is clinically appropriate and will significantly reduce emergency hospital admissions for patients with heart failure, coronary artery disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and schizophrenia.

In some health systems, these medications are already prescribed as part of routine clinical practice. However, there is evidence of significant variation in their use in the UK, USA, and Europe, including under-prescribing and under-dosing. Therefore, policy-makers and clinicians should consider monitoring and improving use of these medications as a strategy to alleviate pressures on secondary acute care.

Existing mechanisms for quality measurement and improvement could be utilized. For example, the UK Quality and Outcomes Framework is a pay-for-performance incentive program that has reduced prescribing gaps and improved prescribing efficiency. The medications we identified should be considered for inclusion in these types of quality assurance and incentive systems.

Our results may also be used to inform shared decision making. When communicating treatment options with eligible patients, clinicians could discuss the ability of these medications to reduce the risk of being hospitalized. Given that most patients prefer to stay out of hospitals, we hope that our findings will help to inform their decisions.

Comments