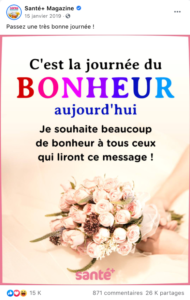

To answer these questions, we examined 6.5 million interactions generated by 500 posts from the Facebook page Santé + Mag. According to some French media, there are concerns about the accuracy of health information disseminated by this outlet.

With 11 million interactions per months and more than 8 million Facebook followers and, Santé + Mag generates five times more interactions than the combination of the five best-established French media outlets. We found that while health misinformation represented 28% of the post published by Santé + Mag, it was responsible for only 14% of the total of interactions it generated (reactions, share and comments). Inaccurate health information actually generated less interactions than other types of content such as social or positive posts.

In fact, Santé + Mag’s main recipe for generating interactions involves the publication, several times a day, of images containing sentences about love, family or the daily life—that we coined “phatic posts”.

People primarily use Facebook to create and reinforce bonds with their friends and family, not so much to share news. As shown by a recent study, “of the 460 min per person per day of total media consumption, approximately 400 min (86%) is not related to news of any kind ”.

Even if a non-negligible proportion of Internet users engage with some misinformation, it doesn’t mean that they believe it or that it will have an impact on their behavior. We analyzed 4,737 comments from the 5 most commented health misinformation posts of our sample and found that most comments were jokes or tags of a friend.

For instance, the post “Chocolate is a natural medicine that lowers blood pressure, prevents cancer, strengthens the brain and much more” was mainly commented by people to tell others that they have a sweet tooth or that they can’t help but eat the whole chocolate bar once opened.

It is important to distinguish the diffusion of inaccurate information from its reception. Sharing is not believing. People may share and interact with content they know to be inaccurate for a nexus of reasons, such as creating bonds with friends or having a laugh.

That said, misinformation can be dangerous. We should rightly be worried about influential actors conferring visibility to misleading and potentially harmful content. But when talking about misinformation, we should not stop at apparently high volumes of interactions and draw alarmist conclusions from it.

Instead, we need to put numbers into perspective and carefully examine the use people make of such content, as danah boyd and Kate Crawford rightly put it: “why people do things, write things, or make things can be lost in the sheer volume of numbers”.

In the same vein, our study showcases the importance of conducting fine-grained analyses of online misinformation as important disparities can hide behind big numbers.

Comments