A new article about Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) – a progressive kidney disease – was published in BMC Medicine today. We spoke to Jochen Reiser, an expert in the field, and Chairman of Medicine at Rush University, Chicago, to find out more about FSGS and what these latest results add to our understanding.

What exactly is Primary Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS)?

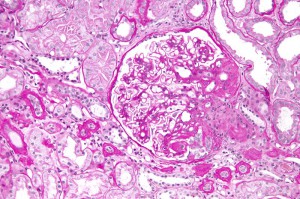

FSGS in simple terms is a progressive kidney scarring disease. The reasons for its development can be several, and stem from inside or outside the kidney. FSGS can recur after kidney transplantation in 30% or more of cases. Given the rapid induction of recurrent FSGS disease, scientists and clinicians suspected the existence of a so called ‘circulating factor’ that is present in the recipient’s blood and which damages the new kidney.

The principle injury target in early FSGS is a cell called a podocyte. Podocytes form a central piece of the kidney’s filtration barrier, and if they fail, they lose their typical ‘octopus-like’ structures and allow plasma proteins to pass from the blood into the urine (proteinuria).

The clinical consequences of proteinuria are manifold and include heightened risk of cardiovascular disease, as well as progressive kidney disorders, eventually leading to loss of renal function and the need for dialysis or renal transplantation.

What is the history behind suPAR as a marker of FSGS, and what is the relevance of this current work?

My laboratory has been studying the behavior of podocytes for many years. We found that they are dynamic rather than static cells. The programs that control their process dynamics are regulated via integrins, cell-matrix anchors that can be active or inactive.

Integrins can associate with the urokinase receptor expressed together with integrins in the same cell or can reach the podocyte from the blood stream in its soluble form called suPAR.

The initial paper describing interactions of the urokinase receptor (uPAR) with integrins came from Harold Chapman’s group at UCSF and was published in Science in 1996. Later, we found that uPAR in podocytes is associated with integrins.

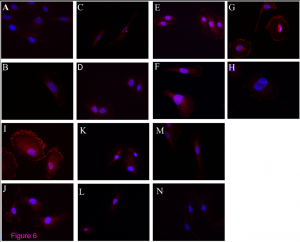

Follow up studies in our laboratory allowed for the identification of suPAR as circulating factor in FSGS. It binds and activates the podocyte alphavbeta3 integrin receptor, thereby causing podocyte dysmotility and early FSGS.

What further research needs to be done?

We identified high serum levels of suPAR in the blood of patients with FSGS. Given the knowledge that suPAR can also be elevated in some other conditions such as inflammation and certain cancers, it became evident that the commercial ELISA (an assay) is not well suited for a single or screening test in a diverse population.

The test is helpful in patients with normal or mildly reduced kidney function and those with an existing diagnosis of FSGS in the sense of being a risk status marker. suPAR in the blood in most, but not all studies, correlates with renal function, but the current ELISA cannot differentiate simple accumulation from pathological production in FSGS in advanced renal failure.

The reason for this dilemma lies also in the fact that ELISA recognizes glycosylated suPAR but not [or poorly] suPAR that is with reduced glycosylation and/or comes as fragments.

We also now know that different suPAR types have different effects on integrins. We can test this with novel cell models and hopefully soon with a specific suPAR ELISA for FSGS. Parts of these detailed studies will be published soon.

What is new about the paper of Huang et al in BMC Medicine?

The paper describes the use of the current available ELISA in urine and the results are stunning. 64 patients with glomerular disease were analyzed for suPAR levels in the urine. Mostly suPAR in FSGS patients was elevated and indicated FSGS, independent of renal function.

I suspect that the biochemical properties of suPAR-types in FSGS are such that they either allow for preferential suPAR excretion or lack of reabsorption. It truly builds the idea that suPAR in FSGS is not just elevated, but elevated and different. So it’s different than in other diseases that can present with high suPAR and no associated renal disease.

The results from this paper suggest we might be able to use the current ELISA by using urine as the kidney leaks out the most toxic suPAR. Furthermore, the authors show that suPAR in FSGS urine can activate podocyte integrin, demonstrating that the suPAR which is measured is relevant to the causes of the disease.

How will this work influence clinical practice?

First, it will stimulate more research and allow the combination of biomarker with pathology, a new direction for nephrology that is very much needed.

Second, a device that removes all suPAR forms is in clinical development and is scheduled for testing in late 2015. Specific removal of suPAR in patients with recurrent FSGS will give the most definitive answer to whether suPAR is a cause or an effect of renal disease.

Third, nephrology research exemplifies a very conservative field. Diversifying ideas, and developing and embracing new concepts does not always come easily. I’m happy to see that suPAR and FSGS is now its own field with close to 50 publications. Only through the collective work of others, will we achieve new goals and develop better treatments.

How will nephrology look in 20 years?

This is a tough question. Pathology and molecular pathways and genetics will all be married together resulting in highly specific and targeted treatments. We might talk of something like an ‘FSGS on biopsy, with APOL1 negative status, suPAR positive, recessive mutation in NPHS2, in a type 1 diabetic’ patient. Treatment would then have multiple components and will probably be (much) more effective than today.

Comments