Welcome to our Meet the SDG3 researcher blog collection. We are interviewing a series of academics and practitioners working in diverse fields to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. You can find other posts in this collection here, and discover what else Springer Nature is doing to advance progress towards achieving this goal on our dedicated SDG3 hub.

Please tell us a bit about yourself.

I am a globe trotter, having moved multiple times during my life and spent time in various places. I completed my Bachelor’s degree at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey (USA) in Cultural Anthropology and Public Health and then completed my Master’s in Public Health (MPH) at Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona (Spain). I am currently a first-year PhD student funded through an AGAUR grant from the Government of Catalonia and EU in Medicine & Translational Research (International Health Track) at the University of Barcelona, Spain, where I also work at the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal) in the Health Systems and Infectious Diseases Research group.

I owe much of my current interests to having grown up with a virologist for a Dad, who would bring me and my siblings to the lab where he was doing his post-doctoral research at Scripps in San Diego, California. The smell of that lab is impossible to forget!

While I didn’t go on to follow entirely in his footsteps or go down a more clinical route (sorry Mom and Dad!), I did stay in the realm of infectious diseases. I, however, took a different approach to infectious diseases and focused my interests around the social, economic, and historical aspects relating to illness and thank my background in anthropology every day. How could we implement any type of health intervention without the knowledge and experience of PEOPLE? I personally think we couldn’t.

Before landing at ISGlobal, three internship positions shaped my research interests, for almost all of which I was supervised by incredible female leaders and researchers in the field. I owe much of my success to these women and their mentorship. In 2012 I spent three months at Hospital Fernández in my native city of Buenos Aires, Argentina, working in the infectious diseases unit and specifically helped with the validation of a portable CD4+ cell count device to be used in resource-limited settings across Argentina.

I later was fortunate enough to work with Tracy Swan and Karyn Kaplan at Treatment Action Group (TAG) in New York City where I advocated for increased HCV treatment access, which at that time included the new and highly effective direct acting antivirals (DAAs).

During the last year of my MPH studies, I interned at the WHO Health Systems Strengthening Office (part of the WHO European Region office) in Barcelona with Dr Melitta Jakab to evaluate non-communicable disease prevention programs in Europe, and also continued to work with my thesis supervisors (Drs Cristina Rius and Mireia Garcia) on vaccine hesitancy among Barcelona healthcare workers.

I joined ISGlobal in 2018 and have since almost exclusively focused on viral hepatitis research. In 2016, the World Health Organization published the first Global Health Sector Strategy on viral hepatitis (2016-2030), which sets ambitious targets for the elimination of viral hepatitis as a major public health threat by 2030. My research over the past years has refined and currently aims to increase testing for viral hepatitis and simplify the diagnostic process, particularly for populations like people who use and inject drugs and migrants, and in resource-limited settings, using novel and simplified diagnostic tools such as rapid testing and dried blood spot (DBS) testing and through unique models of care.

Through my work at ISGlobal and PhD research, I am currently based in Kampala, Uganda implementing a real-world validation study for the screening of viral hepatitis among people attending an HIV clinic in the city. I am working closely with our local partners (Makerere University School of Medicine, Kiruddu General Referral Hospital, and the Central Public Health Laboratory of the Ministry of Health of Uganda) to roll-out this pilot intervention under the guidance of my local supervisor, Dr Ponsiano Ocama.

How does your work relate to SDG3?

My research is directly related to SDG3 which aims to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all, at all ages. Specifically, my research falls under SDG 3.3 which calls for the end of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and to combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases. In order to combat hepatitis and reach the WHO 2030 elimination targets, screening must be greatly scaled-up. Currently, only about 10% of those with viral hepatitis are aware of their status globally. In order to properly address this issue, diagnostic capacities must be expanded. Not only should diagnostic laboratory capacity be scaled up, but the use of simplified sample collection methods and strategies should be more widely accessible and utilized. Rapid detection testing, and particularly in community-based settings, is a suitable way to screen for hepatitis, especially when standard laboratory infrastructure is lacking or key populations face barriers to accessing adequate care.

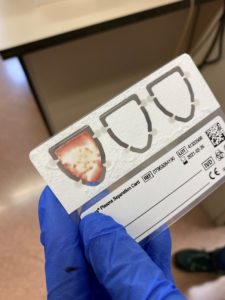

For example, one of the studies I currently coordinate is a community-based hepatitis B screening, linkage to care, and vaccination program (HBV-COMSAVA) among west African migrants living in the greater Barcelona area (PI: Jeffrey Lazarus, ISGlobal; along with Maria Buti, Vall d’Hebron Hospital; Sabela Lens, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona) which uses rapid testing for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in combination with blood sample collection with a novel plasma separation card (PSC). The PSC method was previously validated by colleagues at VHIR with very promising results. Implemented together, these two tools help reach a high-risk community which otherwise may not have accessed care. Positive cases are referred to specialist care via a “fast-track” process at the two collaborating hospitals and negative cases without prior vaccination are offered the first-dose of the HBV vaccine in situ.

What’s the most pressing research question in your field, and what are your hopes for progress in the future?

The Sustainable Development Goals directly call for combatting viral hepatitis, and the WHO set the ambitious goal of eliminating viral hepatitis as a major public health threat by 2030, making this issue a clear global health problem for us to tackle. It is estimated that 320 million people are living with viral hepatitis: hepatitis B, 250 million, and hepatitis C, 70 million, and these two viruses are the leading contributors to liver cancer deaths globally. The majority of HBV cases can be found in South East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, two regions with weak health systems and poor diagnostic capacity.

We can’t achieve SDG3 or reach the WHO elimination goal if priority and funding isn’t given to these regions to help scale up screening, linkage to care, and treatment. Across Africa, particularly, the implementation of the birth-dose HBV vaccine is crucial to help prevent mother to child transmission and prevent early childhood infection since 90% of children infected in childhood go on to be chronic hepatitis B carriers, adding to their risk of liver cirrhosis and cancer. Currently, however, the global birth-dose vaccine coverage rate is around 38%.

Scaling up both hepatitis testing and expanding access to the HBV birth-dose vaccine require that North-South partnerships (such as those with Gavi; EDCTP; or research collaborations) be people-centered and led by those truly aware and sensitized to the realities lived by people who are affected by these weak health infrastructures. Organizations like the World Hepatitis Alliance are on the frontlines of fighting for a world free of viral hepatitis and call for us to #FindTheMissingMillions.

We know viral hepatitis is a major problem, so it needs to become a priority for policy-makers, physicians, researchers, and academics alike with proper financing mechanisms in place to scale up the needed tools and interventions.

Please describe hurdles you’ve come across during your career.

I believe that one of the biggest hurdles affecting viral hepatitis research globally is the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. This is true both for researchers as individuals, but also for research agendas.

Firstly, the burden and stress experienced by virtually everyone through national policies like country-imposed lock downs, physical distancing measures, curfews, and the closure of businesses both big and small has had a toll on many. For me, in particular, this stress coupled with the fact that I was far away from my family brought on a great deal of despair and uncertainty. To cope, however, I did join the “get an animal” club and welcomed a kitty to the family!

In regards to research agendas, the COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to de-rail progress made towards reaching the WHO elimination targets. We know from past experience and other research that social, political, and economic instability can propagate health inequalities and undermine existing health systems, as was seen during the 2015 Ebola crisis in West Africa.

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, routine services have been disrupted with some recent studies suggesting that up to 95% of viral hepatitis services were affected. Disruptions include decreased or no testing, delayed treatment initiation or the inability to refill prescriptions, and missed vaccinations. These disturbances in care provision can particularly affect LMICs with unstable health systems but also vulnerable populations, both in LMICs and HICs.

We wanted to explore how the COVID-19 pandemic affected harm reduction centres in Spain- spaces crucial in combatting hepatitis C infection and other blood-borne infections. Our research showed that harm reduction centres operating across Spain where able to adapt or modify their services. However, there was a clear decrease in the rate of testing and needle distribution suggesting that fewer clients accessed life saving harm reduction services during this time, putting them at greater risk of reusing or sharing injecting equipment, overdosing, acquiring infectious diseases with decreased access to testing or discontinuing ongoing treatment such as methadone maintenance therapy, hepatitis C treatment, or antiretroviral therapy.

While it is still too soon to tell how the cessation of routine viral hepatitis services, such as HBV vaccination in LMICs or harm reduction centres, may impact the global progress towards hepatitis elimination, it is estimated that it will impact disease dynamics and transmission. With that being said, the impact of this pandemic may persist well after the COVID-19 pandemic is deemed “under control”.

Please tell us about a resource or person that has particularly inspired you?

As someone with a degree in Anthropology, I have always found Dr Paul Farmer to be an incredible inspiration. I’ve recently read his latest book Fevers, feuds, and diamonds: Ebola and the ravages of history and was once again reminded that the way people experience health and health services are directly intertwined with history, culture, geography, politics, and everything in between. Health and wellbeing aren’t a dichotomy of “sick” versus “healthy”- health is a confluence of everyone’s circumstance, both past and current. Dr Paul Farmer has reminded me of that in many of his readings. It’s not enough to see people as mere subjects in our research, we must always remember that they are, above all, humans with stories, emotions, and opinions that can help better the way we offer health services, communicate health and healthcare, and reach patients- particularly those who are oftentimes marginalized in society or forgotten altogether.

We must all work together – patients, researchers, healthcare providers, academics, and policy makers – to move towards Universal Health Coverage for all and ensure the quality of care is equal for all, irrespective of gender, race, age, or geographical location. In doing this, we will hopefully take strides in achieving SDG3.

You can find other posts in this collection here.

At Springer Nature we are committed to playing our role in advancing progress towards achieving SDG3 by both supporting researchers and being an active voice, promoting an interdisciplinary evidenced-based approach to all targets and indicators within this goal. Learn more about our SDG3 activities and the Springer Nature SDG Programme.

Comments