Among cancers affecting both men and women, colorectal cancer is the second leading cancer killer in the United States. But if everyone aged 50 years or older had regular screening tests, at least 60% of deaths from this cancer could be avoided.

Our recent article in Translational Behavioral Medicine (Implementation of an Evidence-Based Intervention to Promote Colorectal Cancer Screening in Community Organizations: A Cluster Randomized Trial), reports the outcomes of a trial in which a research-tested intervention to promote colorectal cancer screening was implemented in 17 community organizations that serve the Filipino American community in Los Angeles County. Our group developed and tested this intervention in a previous trial.

Why Filipino Americans?

They are the second largest U.S. Asian group after Chinese Americans, and they have low rates of colorectal cancer screening and low 5-year survival rates.

Why community organizations?

Filipino Americans love to gather. Our prior work suggests many Filipino Americans belong to 2-3 organizations. Therefore, community organizations may be a good venue to encourage colorectal cancer screening for Filipino Americans, even those who do not see a doctor on a regular basis.

But health promotion is not the primary mission of community organizations such as churches, senior centers, and social service organizations. How many organizations will be willing to take on this responsibility? What type of technical assistance and resources will these organizations require? How successful will they be in recruiting participants who are not up to date with colorectal cancer screening? Will they be able to implement the intervention with fidelity? These are just some of the questions that motivated our study.

As explained in more detail in our article, we trained community members at each participating organization to serve as community health advisers. They recruited members of their organizations who were not up to date on colorectal cancer screening, and conducted educational sessions on colorectal cancer and screening methods, based on a curriculum we provided. They distributed free fecal occult blood test (FOBT) kits and print information in English and Tagalog, and urged participants to discuss colorectal cancer screening with their physician. They referred participants who did not have a usual source of care to a community clinic that evaluated their FOBT kits and charged it to the study.

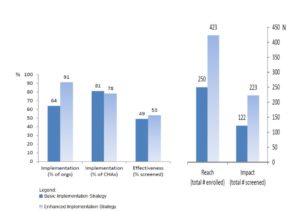

The study compared two levels of technical assistance provided to organizations in two arms of the study: the basic implementation strategy and the enhanced implementation strategy. Community health advisers in both arms of the study received the same initial 6-hour training. Organizations randomized to the enhanced implementation strategy received additional booster sessions for community health advisers. The enhanced strategy also engaged organizational leaders in addition to community health advisers.

Despite similar effectiveness of both strategies (49% of participants got screened in the basic arm, 53% in the enhanced arm), implementation by more organizations in the enhanced implementation arm increased the reach (number of people enrolled) and impact (number of people screened) of the program substantially.

While this trial answered some of our questions, many questions remain.

For example, we were surprised about the relatively high screening rate among participants and offer a few potential explanations for this in the article’s discussion section. Our trial succeeded in reaching Filipino Americans who have low levels of income and lack of health insurance—two characteristics shown to be associated with lack of cancer screening. But will organizations be able to maintain this program after the end of the trial? Turnover of program staff and organizational leaders may require additional training and capacity building activities to maintain program activities. Future studies should examine what resources would be required for community organizations to sustain cancer screening and other health promotion programs.

Do you think community organizations can play a role in reducing colorectal cancer disparities? How can community organizations contribute to reaching the national goal of reaching 80% screened for colorectal cancer by 2018?

Please share comments, questions, and relevant experiences.

There have been quite a few initiatives to reach these communities. As in this study, the screening rates have remained unchanged for many years despite the valiant efforts. A blood test for screening non-compliant individuals was just approved by the FDA (Epi proColon). Having a blood test choice for these non-compliant individuals may help outreach efforts and impact the screening rates.