Questions about the coevolution of genes and languages have fascinated scientists and the general public for decades. Previous population genetic studies that have considered the spatial and temporal aspects of the spread of peoples and languages, including the influential work of Luca Cavalli-Sforza and many others, have significantly improved our understanding of the genetic landscape of contemporary populations.

Together with many collaborators from all over the world, our group at the University of Tartu has contributed to this field by studying possible connections between the cultural aspects and genetic diversity of the speakers of Balto-Slavic, Turkic, Austroasiatic and Austronesian languages.

It was intriguing to study the roles of geographical neighbors and common linguistic heritage in shaping the genetic similarity patterns among these populations.

In our recently published article, we performed the first whole genome-scale analysis of the so far genetically understudied Uralic speaking populations covering all of the main existing groups of the linguistic family. In this study, the data of genetics and linguistics of the Uralic-speaking populations were studied jointly for the first time.

What are Uralic languages?

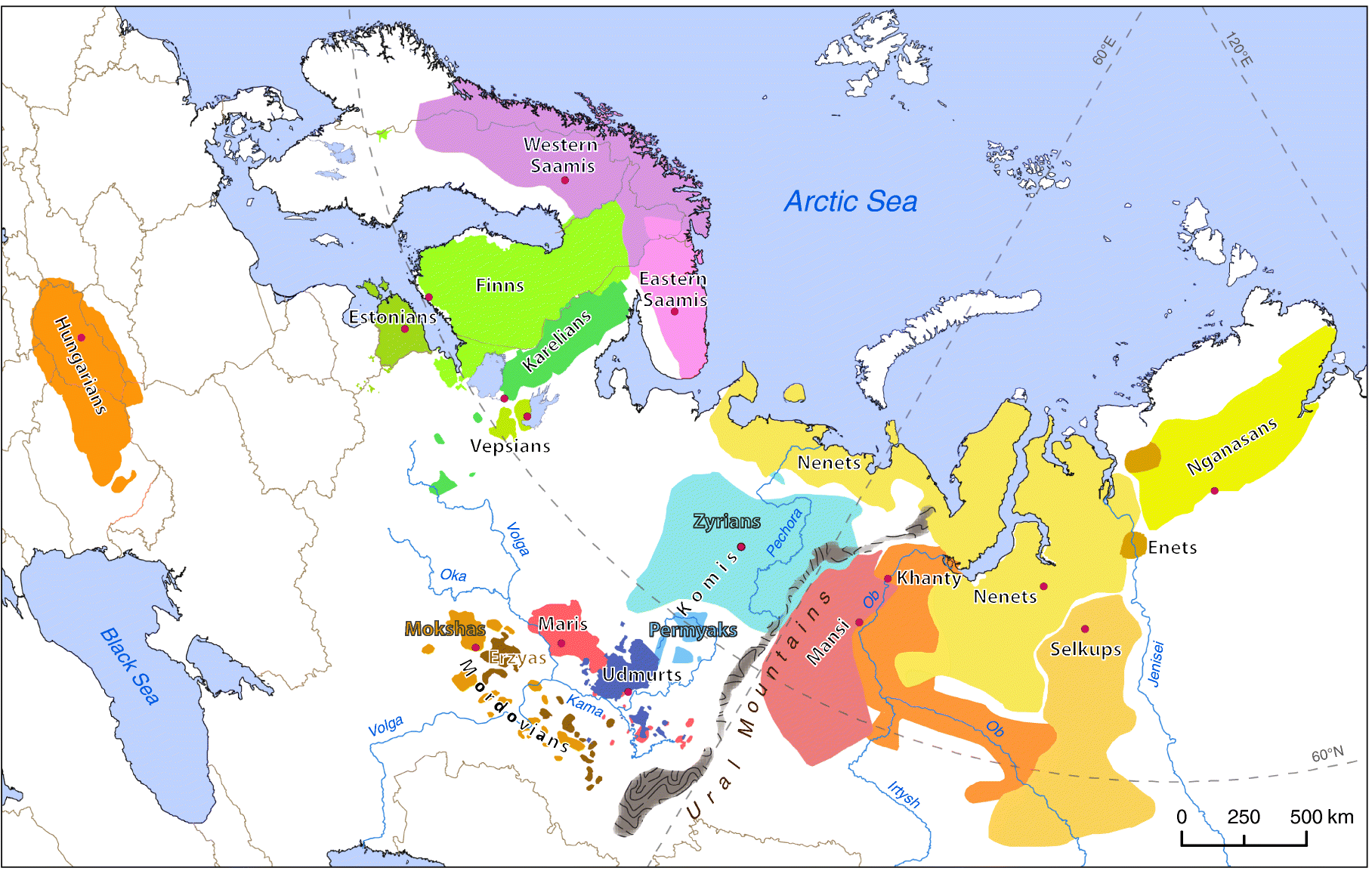

Uralic speaking groups are today sparsely spread over a vast area, mainly in Northwestern Eurasia as cultural pockets in an otherwise largely Slavic or Turkic realm. Hence, it was intriguing to study the roles of geographical neighbors and common linguistic heritage in shaping the genetic similarity patterns among these populations.

According to a classical view of linguists, the common ancestor for all present-day Uralic languages – the proto-Uralic – was spoken 4000-6000 years ago in the territory near the tributaries of the Kama and Volga Rivers at the easternmost border of Europe. From there, Uralic languages spread towards the west but also to the east of the Ural Mountains.

In total, around 40 languages spoken by a limited number of 25 million people belong to the Uralic family. Hungarian, Finnish and Estonian are the largest and have the status of national language.

Linguistic relatedness and genes

We wanted to shed light on the questions about how similar the Uralic speakers from different geographical locations are to each other genetically and how much, if any, of their linguistic relatedness is reflected in their genes.

What we already knew from earlier studies was that there are sex-specific differences in the demographic history of the Uralic-speaking populations. The maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA lineages of the Uralic speakers resemble those of their geographical neighbors throughout the Uralic area. In the western side of the Ural Mountains, they are quite similar to other European populations and in the eastern side of the Ural Mountains, they resemble Eastern Eurasian populations.

The paternally inherited Y chromosomes of the westernmost Uralic speakers in Europe are, on the contrary, shared largely with West Siberians, indicating a gene flow between these two regions and raising a question about whether this might be associated with the spread of some of the Uralic languages.

No one had tackled the question of the genetic variation of Uralic populations from the whole genome perspective coupled with the linguistic data before now. In accordance with our expectations, we found that the Uralic-speaking populations are genetically most similar to their local geographical neighbors, regardless of their linguistic affinity. However, we also found three types of evidence that the possible gene-language coevolution might have taken place in the Uralic-speaking group.

Firstly, we found that the Uralic-speaking populations share a distinct ancestry component according to their whole genome-wide data. We showed that this ancestry component is likely of Siberian origin, being most visible in West Siberian Uralic-speakers. It constitutes one third of the genetic legacy of the Volga-Ural region Uralic speakers and Scandinavian Saami. It is less than 10% among Finns and Estonians and is largely absent in the rest of the Eastern coast of the Baltic Sea and further south and west.

Geographically distant groups of Uralic speakers have significantly more shared recent genomic ancestry components with each other than with equidistant groups speaking other languages.

Secondly, when we quantified the common recent ancestry between the Uralic-speakers using the method that counts shared identity-by-descent genomic blocks between populations, we found that geographically distant groups of Uralic speakers have significantly more shared recent genomic ancestry components with each other than with equidistant groups speaking other languages.

Thirdly, when analyzing genetic datasets jointly with linguistic data, we found a significant positive correlation between these two datasets of the Uralic-speakers and thus had additional support for our conclusion that the spread of the Uralic languages has occurred with at least some level of associated gene flow.

Two interesting exceptions to the pattern of gene-language co-evolution are Hungarians and Estonians. We did not find long-range genetic ties between those two populations and their linguistic relatives that would distinguish them from their non-Uralic-speaking neighbors in whole genome-wide analysis.

However, we did see similarities of Estonians with geographically close Uralic- speakers in the North-eastern European group – with Finns, Karelians, Vepsas and the Saami. Also, through their Y chromosomal gene pool Estonians have connections further east as they share a considerable proportion of paternal lineages with Volga-Ural and West Siberian populations.

Our whole genome-wide study combined with our earlier knowledge about the variation of maternal and paternal lineages among the Uralic-speaking peoples shows that most of the present-day Uralic-speakers have traces of their recent common history in their genes.

The next question would be whether the timing of the arrival of the gene flow from the east to the territory where the westernmost Uralic-speakers live today falls into the same time window as the proposed diversification of the westernmost branches of the Uralic languages. This remains to be studied with the help of ancient DNA samples from the territory of the Northeast Europe and eastern coast of the Baltic Sea.

Kristiina Tambets, Terhi Honkola & Mait Metspalu

Dr. Terhi Honkola is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Turku, Finland, in a multidisciplinary BEDLAN research group. After obtaining her MSc degree with evolutionary genetics as her major, she dived into the world of multidisciplinary research to study linguistic divergence and human past by applying quantitative biological methods to language data.

Dr. Mait Metspalu is a senior researcher and a director of the Institute of Genomics at the University of Tartu, Estonia. Mait Metspalu studied geography and molecular biology and evolution at the University of Tartu where he also defended his PhD on phylogeography of human mitochondrial DNA in South Asia in 2006. His research concentrates on using and developing population genetics approaches to understand the genesis of the genetic diversity patterns of humans through reconstructions of past population movements, splits and admixtures as well as adaptations to local environments.

Comments