The host animals from which a female mosquito takes her blood meal influences the pathogens she can be exposed to and, by extension, the potential role her species may have as a vector of disease. In this post, I outline my recent research investigating the vertebrate species fed on by mosquitoes in the United Kingdom.

The UK plays host to some 34 species of mosquito, with the eggs of a potential 35th, the invasive Aedes albopictus, having been detected late in 2016. Although no mosquito-borne pathogens of veterinary or human importance are currently thought to circulate in the UK, several species are known vectors of pathogens including important viruses and malaria. In addition, many species are known to cause a considerable biting nuisance to humans.

Our understanding of the feeding behaviour of our native mosquitoes is fairly limited however, particularly in regards to which bird species are fed upon.

Farms as environments for mosquitoes

As part of my doctoral work I focused on understanding mosquito-host interactions on livestock farms. Farms are interesting study sites as they are home to various wild and domestic mammals (plus humans) and provide natural and artificial structures and habitat for a multitude of insects, including mosquitoes. My research, recently published in Parasites and Vectors, posed the question: which animals are farm-associated mosquitoes feeding on? I elected to find the answer at a coastal grazing marsh on the Isle of Sheppey in Kent, an area long associated with high mosquito densities and historical vivax malaria transmission.

Collecting blood-fed mosquitoes

By far the most challenging aspect of working with blood-fed mosquitoes is collecting suitable numbers of them from the field. After blood-feeding, females will find an area where they can safely rest and digest their meal. This process takes several days depending on the species, volume of blood consumed and the environmental conditions. Blood-fed individuals are poorly attracted to the most commonly-used mosquito traps which use light and/or host-derived scents as bait.

With this in mind, I turned to aspiration from buildings, chicken coops and resting boxes as my main approach to collection. My resting boxes were glorified packaging crates which provided shelter for resting mosquitoes, from where they could be aspirated.

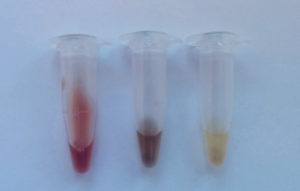

Once back in the lab, mosquitoes were crushed into solution, DNA extracted and a PCR-sequencing approach targeting the mitochondrial gene cytochrome c oxidase I used to identify the origin of the blood meal.

The collections yielded over 20,000 mosquitoes of 11 species (although mainly the indoor-resting Anopheles maculipennis s.l., Culiseta annulata and Culex pipiens s.l.). Ten percent of these specimens contained a blood meal. From these, the host blood meal origin was identified in 964 specimens.

Blood meal sources

Mosquitoes had fed on nineteen different hosts, comprising 14 birds and five mammals. As only one native bird – the pigeon – has previously been identified as a host in the UK, the bird results were particularly welcome. Intriguingly, one host was the dark-breasted barn owl, a sub-species (Tyto alba guttata) of the native white-breasted variety, not known to occur in the area and which is an infrequent visitor to the UK’s east coast from mainland Europe.

This finding demonstrates the potential for blood meal analysis to be used as a tool for tracking rare species for conservation purposes. Two long-distance migratory birds – the yellow wagtail and barn swallow – were also identified as hosts. Migratory birds have been implicated in the long-distance dispersal and introduction of mosquito-borne pathogens to other parts of the world and are considered a potential way for novel pathogens to enter the UK.

What determines blood meal source?

Surprisingly, no human blood meals were identified from any specimen. We know from other studies (and personal experience!) that humans are readily bitten by mosquitoes on site. Therefore, this result likely reflects the importance of host availability in determining mosquito feeding behaviour. Fewer than 10 humans are usually present in the area during peak (crepuscular) biting times and therefore the relative proportion of human blood meals may be too low for detection in this study.

Indeed, current evidence indicates that whilst certain mosquito species may preferentially take blood meals from some hosts or host groups over others, the evidence for this being a solely intrinsic (i.e. genetic) vs. an environmental phenomenon (e.g. due to the availability of hosts) is less clear-cut.

Here, within the same study area, species such as Culex pipiens form pipiens fed exclusively on birds (13 species), whilst others, such as Anopheles atroparvus, fed more widely on both mammals (5 species) and birds (2 species). Interestingly, nearly all An. atroparvus collected from the chicken coops had fed on chickens, whereas those feeding on chickens and other birds in other trap locations, and in the literature more widely, is more limited.

This illustrates the bias introduced by collection method and location, which complicates the interpretation of the results of blood meal studies; a useful review on this topic is available here.

The importance of determining blood-feeding behaviour

The rapid and destructive emergence of the Zika virus in South America has demonstrated the continued relevance of mosquito-borne disease worldwide. Amassing data on mosquito behaviour in currently disease-free areas such as the UK will better facilitate control efforts in the event of emergence.

My conclusions

In returning to my original question, this study found that farm-associated mosquitoes feed on a range of livestock and wildlife species. The data generated in this study contributes vital information concerning avian species that could introduce a mosquito-borne pathogen into the UK and those animals and mosquitoes that might be involved in local transmission cycles following such an introduction. Finally, I hope that the successful use of resting boxes demonstrated in this study will encourage others to deploy these simple yet effective collection devices in future studies of blood-feeding behaviour.

Comments