Almost a year ago  today, an alarming report was published by the French Institute for Public Health Surveillance (InVS) describing a novel mosquito-borne disease on the Caribbean island of St. Martin. A patient, who started having symptoms of fever, joint pain and fatigue, was diagnosed with chikungunya virus infection. This started the first documented outbreak of chikungunya in the Americas. I remember trying to explain the reason for my horror at this to colleagues, friends and relatives during the Christmas holiday last year, and I’m sure many of you did the same.

today, an alarming report was published by the French Institute for Public Health Surveillance (InVS) describing a novel mosquito-borne disease on the Caribbean island of St. Martin. A patient, who started having symptoms of fever, joint pain and fatigue, was diagnosed with chikungunya virus infection. This started the first documented outbreak of chikungunya in the Americas. I remember trying to explain the reason for my horror at this to colleagues, friends and relatives during the Christmas holiday last year, and I’m sure many of you did the same.

.

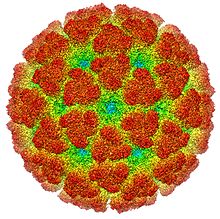

For those of you not yet familiar with this disease, chikungunya fever (pronounced as “chik-en-gun-ye”, here you can hear the correct pronounciation) is a disease caused by the chikungunya virus. It is a member of the Alphavirus family, a relative of e.g. Ross River virus found in Australia. It is transmitted by mosquitoes in the Aedes genus, predominantly the yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti) and the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus). Chikungunya fever is characterized by fever, headache, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, muscle pain, rash, and joint pain (https://www.cdc.gov/chikungunya/symptoms/). Fatigue and incapacitating joint pain can last for weeks or months. The pain is apparently so bad that it gave rise to the name of the diseases, based on the term “chikungunya” meaning “that which bends up” in the Kimakonde language of Mozambique. There is no licensed vaccine (although there is ongoing vaccine development), and there is no specific antiviral therapy available, only supportive treatment (i.e. painkillers). The only good thing about this pathogen is that the number of deaths attributed to infection is low.

The virus was first found in 1953 in Tanzania, and until recently was considered one of many minor mosquito-borne diseases in Asia and Africa. However, a single mutation from alanine to valine at position 226 of the envelope glycoprotein of the virus led to increased adaptation in terms of infectivity to Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. This adaptation led to a large outbreak in the French Island of Reunion in 2005-2006, which then spread further through the Indian Ocean to the India and SE Asia in general. In 2007, a returning traveller from India initiated an outbreak in Ravenna, Italy, which resulted in 205 local cases. In 2014, 11 cases of locally acquired chikungunya were confirmed in SE France.

During its 1st year, the chikungunya outbreak in the Americas has become a really big boy! As of December 12, 2014, there have been 1,031,757 suspected and confirmed locally transmitted cases documented across 43 countries. The only countries without documented local transmission at this point in time are Argentina, Bolivia, Canada, Chile, Cuba, Ecuador and Peru. As vectors are present in some of these countries the lack of documented cases might be due to a lack of surveillance or transparency rather than lack of transmission. These huge numbers still reflect only a portion of the true number of cases. For instance, in Puerto Rico only 20% of laboratory confirmed cases had been diagnosed with chikungunya and only 8% of cases were reported to the Puerto Rico Department of Health. This may be because a portion of cases are mild or asymptomatic, as have been 40% of all cases on St. Martin. This is significantly higher than during previous outbreaks, such as on Reunion. In addition, in many of the countries involved patients might self-medicate outside of the public health system during a chikungunya outbreak and therefore not be detected. I have heard from @DokteCoffee that this occurred on Haiti. Project Tycho at the University of Pittsburgh has created the best animation I have seen so far showing the spread of chikungunya across the Americas, but this only went to the end of August 2014.

.

While chikungunya is generally regarded to have a low mortality rate, 115 deaths have been attributed to the disease so far, mostly in very young or very old patients with other co-morbidities. One consequence of large localized chikungunya outbreaks is the collapse of local health systems due to the large number of patients seeking help, such as happened in Colombia. Another issue is the potential economic effects, both due to lost productivity, and the reduction in tourism in affected countries.

.

So what can we expect in the 2nd year of chikungunya in the Americas? We can be sure that chikungunya won’t just disappear, and it hasn’t yet finished spreading and infecting people in new locations. While many countries such as the Dominican Republic had hundreds of thousands of cases, local transmission is only starting in other countries such as in Paraguay. On St. Martin, seroprevalence studies found that 12-20% of the population has been infected, which is still lower than the seroprevalence at the end of the outbreak in Reunion, so transmission might still continue for many months. If 20% of the population in all of 43 countries with local transmission becomes infected, that would mean many millions more cases by the end of next year. Eleven locally transmitted cases were reported in Florida, as well as 1900 imported cases. In addition to Florida, Aedes aegypti is also present in southern Texas, in several counties of California, and even in isolated locations in Georgia, providing conditions for local transmission in these areas as well.

Alarmingly, a different strain of chikungunya has been detected recently in Brazil. This strain is more adapted to the Asian tiger mosquito. Fortunately, it doesn’t yet have all the mutations that make it the most efficient at infecting the mosquito, but that might change rapidly. If this strain became widespread, the current outbreak might expand to all areas in the Americas where Aedes albopictus is endemic, including the eastern US

.

Last years developments spurred a fresh wave of attention and investment in controlling chikungunya and its vectors. First of all, the large potential market of millions American snowbirds going to the Caribbean every year spurred the acceleration of vaccine development. Although an experimental vaccine has just passed Phase I trials recently, it might take years until it gets licensed by the FDA. The threat has mobilized the U.S. Military as well – the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has issued a challenge on Innocentive to forecast the future dynamics of the outbreak. I myself have tried responding to their challenge, but gave up after I realized that the method I was trying has already been done by the CDC months before.

.

However, when I last logged in, there were hundreds of active participants, and I will be very interested to see the tools they’ll produce at the end. For now, we have to accept the fact that chikungunya has become another fact of life in most of the Americas, just as dengue has, and that we can only protect ourselves and our loved ones by protecting against mosquito bites. What we can do in other countries is to maintain and increase awareness, and educate the general public, especially those traveling to Central and Southern America and the Caribbean, to the dangers of chikungunya and mosquito bites in general.

I had this disease when I was only 14 years old. It was having an outbreak ( it still unresolved today) on my country. It was very awful!, first I had only two days of high fever, I don’t had ronchas en mi piel, but i had 8 months of an excruciating joint pain. I wasn’t able to write. It was very sad. Sorry if you found any written error, it because I’m learning English, so, be patient with me, please.