Welcome to our SDG Editorial Board Members blog collection. We are hearing from the Editorial Board Members of the BMC Series journals whose work aligns with achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Here you can find other posts in this collection, grouped with the tag ‘SDG editorial board members‘.

Do you know what I do when am in tropical rainforests? I collect mosquitoes. Yes! I’m a biologist with a passion towards public health studies and my research field connects with two sustainable development goals (SDGs), SDG3 – Good health and well-being and SDG15 – Life on land. Here I want to tell you about the challenges and the successes of achieving the SDGs in my field of research.

Malaria is still a public health issue in the Brazilian Amazon and its transmission occurs in deforestation frontiers, the human-nature interface. Deforestation is the result of impoverished locals who undertake slash-and-burn activities on their own lands as a way of living. Clearings in patches of tropical rain forests create conditions for the larval habitats of the dominant malaria vector (Anopheles darlingi). When the anopheline larvae emerge into flying adults, adult females fly on seeking human hosts in the nearby houses. When these anopheline females bite a person carrying malaria parasites, they get infected and send propagating malaria parasites to the whole community.

Undertaking mosquito collections is an enormous task in the Amazonian settings. Every field plan must be reassessed as conditions turn out to change quickly during the days of field collection. Numerous methods for catching mosquitoes are used. One of them is the barrier screen (above) on which anophelines land and can be captured by us using small electric-powered aspirators. Field collections may last all night long (12 hours), which means everyone in the team has to stay awake during the night and sleep during the day.

Back in the lab with samples of anophelines, specimens are identified at the level of species and then tested for the presence of malaria parasites. Each malaria microcosm site has its landscape analyzed by remote sensing and satellite imagery from the initiation of colonization in the 1970s until now.

Altogether, 80 malaria microcosm sites all over the Amazon region were studied during our research project and the results have been published in Scientific Reports.

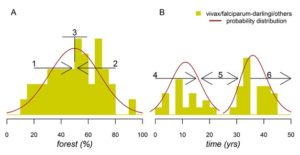

The main results obtained were: (A) malaria risk is greater when accumulated deforestation reaches 50%, (B) two temporal malaria peaks occur: one at 10 years and a second at 35 years after settlement initiation.

Our results ultimately show that the loss of forest cover supports the transmission of human malarial parasites over time in the Amazon. These results can be translated to policies aimed at public health intervention designs for enhanced health of locals and in favor of conservation of tropical rain forests and education of locals for keeping the forest up, complying directly with SDG3 – Good health and well-being and SDG15 – Life on land. Translational science in our field of research depends heavily on policies that are implemented by the government. With the proof of concept and scientific evidence that could be obtained from this research project, it is more likely that these policies can come to life and help in sustaining good health and well-being and life on land.

Comments