We estimate that over 3% of the world’s population required humanitarian aid in 2020. As temperatures rise and weather patterns shift, one can only imagine the number of people and financial resources needed to provide services if we continue unabated on this current dangerous path. We lack accurate figures but hypothesize that the destruction of formal structures and social safety nets during natural disasters will likely lead to increases in violence against children.

When disaster strikes, we often do not have time to ask questions of how and why violence occurs. We create research that is responsive and immediate, focusing on enumeration of children at highest risk of violence or top concerns of affected communities. However, if we do not understand fully which aspects of the disaster leads to violence, how can we prevent it?

This question has echoed in my head many times over the years, as I spent the better part of a decade conducting research on child protection violations in humanitarian emergencies. Those who work in disaster response and humanitarian emergencies are guided by the premise that we do not cause harm, and therefore, our interventions are needed and justified. Corresponding research is process driven to improve upon existing service delivery. I often wondered if we could create a more public health approach that targets the upstream drivers of violence.

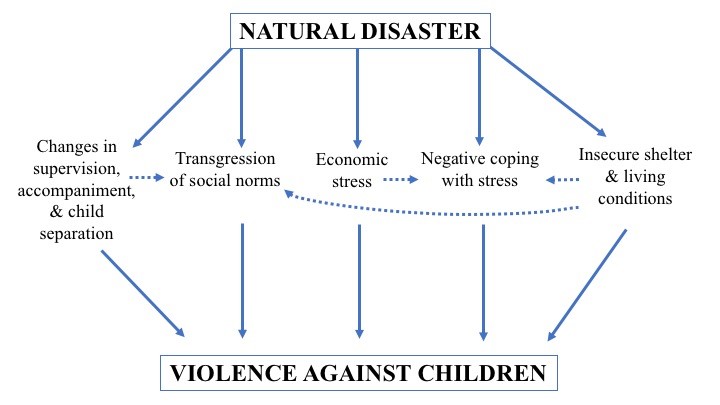

Our systematic review published in BMC Public Health collates information on the potential pathways between natural disasters and violence against children to suggest points of intervention. We identified five pathways to violence:

- Environmentally induced changes in supervision, accompaniment, and child separation

- Transgression of social norms in post-disaster behavior

- Economic stress

- Negative coping with stress

- Insecure shelter and living conditions.

The findings have three major implications for action. First, while it is likely that a greater number of pathways exists, given the scarcity of the evidence, we can say with assurance that intervening on each of these aspects of the post-disaster environment would help to prevent violence. Violence prevention programming should structure interventions that target these five pathways after natural disasters.

We have a wealth of evidence-based interventions that can be utilized; for instance, SASA! (meaning “now” in Kiswahili) for social norms change, Parents Make the Difference for positive parenting, and Cure Violence for creating safe environments. Global standards in the Minimum Standards for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action (CPMS) and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) INSPIRE: Seven Strategies for Ending Violence against Children should be met in building interventions.

Second, we should leverage the already existing knowledge and resilience of communities whom often experience natural disasters cyclically. We found that some families and communities were able to protect children from violence after natural disasters, particularly in terms of creating new accompaniment and supervision structures. Natural disasters may be unique from armed conflict in that community trust is greater intact.

We should look to indigenous knowledge that bolsters local response. These strategies are likely to be effective, more easily promoted than external interventions, and supportive of efforts to localize response. We highly encourage greater documentation and evaluation of positive behaviors after natural disasters that work to prevent violence.

Third, multi-pronged approaches are essential in preventing violence. The five outlined pathways individually lead to violence but do not act in isolation. Programming must be created to combat multiple pathways.

Suppose a service provider creates a livelihoods program to address the economic stress pathway to violence. Unconditional cash transfers are provided to women heads of household in an effort to ensure that money is used for family needs. Violence against women and children may still occur in societies where it transgresses gender norms for women to be breadwinners of households. Humanitarians may cause more harm than good if they do not bundle livelihoods interventions with social norms change.

The livelihoods intervention further does not alleviate other negative coping behaviors. Violence against children may still occur if women caregivers are not provided with parenting programs and mental health support to cope with acute and ongoing stress from the natural disaster.

Without addressing all pathways, violence against children will likely continue to occur. Individual agencies should design comprehensive interventions that address multiple pathways to violence, and humanitarian coordination mechanisms can ensure that no gaps exist in government and agency services.

Comments