I am a nurse scientist and health services researcher. I was born and raised in a series of small towns in rural Washington State in the U.S. In September 2009, I returned to the Pacific Northwest to pursue a PhD. It was the height of the Great Recession (2008-2009) and I quickly became concerned that the recession was making it harder for people to access care in the kinds of resource-poor areas similar to where I grew up. I decided to focus my dissertation work on this area and started by carrying out interviews with public health stakeholders around Washington State. Interviews yielded widespread concern about the effects of the recession — particularly among maternal and child health (MCH) populations. Disparities in MCH outcomes like timing of entry to prenatal care (PNC), birth weight (BW), and infant mortality are long-standing and have been documented by race/ethnicity, geography and other social characteristics groupings like education and insurance status.

My research

To explore the effects of the recession, I obtained de-identified birth certificate data from Washington State and Florida. Birth certificate data was a good fit because it allowed me to link to county level data including unemployment rate, local health department expenditures, and other community characteristics that were likely to change during the recession. Over the course of three related papers, published in Race and Social Problems and BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, my co-authors and I analyzed relationships between MCH outcomes and disparities before, during, and after the Great Recession.

What did we find?

Increases in disparities – worse outcomes

In our first paper, we used Healthy People protocols to assess the degree of disparities and the extent to which changes occurred during and after the Great Recession for seven MCH outcomes. As expected, we found that disparities increased for some groups during the recession. However, we surprised to find that there were more total increases in disparities in Washington than in Florida and more disparity increases after the Great Recession than during.

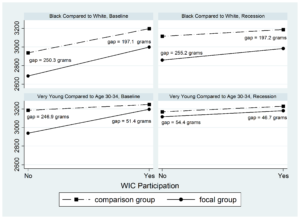

WIC appears to have been beneficial for decreasing disparity gaps in infant birth weight.

The majority of increases only occurred during one recession period (i.e. during or after but not both), but disparities for some groups and some outcomes increased during both recession periods. For example, among non-Hispanic Black mothers who entered prenatal care late or not at all (late/no PNC) disparities increased (outcomes worsened) during both recession periods. Disparity increases also appeared to predominantly cluster by race/ethnicity and individual social characteristics rather than by geography. Based on these findings, we focused further research on factors contributing to increasingly disparate outcomes in timing of PNC initiation.

Predictors of late/no prenatal care

In our second paper, we used regression modeling to estimate relative contributions of individual, community, and local health department (LHD) variables on the probability of late/no PNC in Washington and Florida. Here, we found consistent contributions over time of individual-level maternal predictors for late/no PNC, the largest of which were young age and low education. However, we did identify changes in associations before compared to during the recession for some community and LHD-level predictors (e.g., % voting Republican, LHD expenditures) in non-beneficial directions.

In contrast, women enrolled in the WIC Special Supplemental Nutrition Program had a lower probability of late/no PNC than those without WIC. These findings suggest that policy makers and providers should consider targeted outreach to pregnant women with high individual-level disadvantage characteristics—particularly those of young age or with low education.

WIC and improved outcomes

In the third paper, we studied interactions between enrollment in the WIC Program and individual characteristics in relation to birth weight. We focused on a high-need subset of the study population — those with Medicaid or no insurance. We found that WIC interactions were associated with higher birth weights for infants of mothers who were very young (age <14), received late/no PNC, and among non-Hispanic Black infants. These effects are illustrated in the figure below for birth weight in grams among Black compared to White infants and infants of very young mothers compared to mothers age 30-34, with and without WIC, both before and during the recession. While disparities persisted during both periods, with or without WIC, the gap narrowed for infants of mothers who received WIC during their pregnancy.

What can we learn from this?

The ongoing coronavirus pandemic and associated unfolding economic and social crises bear similarities to the Great Recession and there are many lessons to be learned from it and applied to the current situation. Three key takeaways from our studies are summarized here:

- Inequality in the U.S. continues to be multi-generational, with disparities in access to care and outcomes apparent before and at birth.

- During the Great Recession, disparities increased and widened in both Washington and Florida, despite differences in state-level economic circumstances and demographics, highlighting the need for dedicated public health funding and programs to support timely, ongoing data collection and analysis to identify and address disparities in care and outcomes at local, state, and federal levels.

- WIC appears to have been beneficial for decreasing disparity gaps in infant birth weight among the very young, Black, and late/no prenatal care enrollees. However, these benefits did not appear to extend to all groups. Thus, targeted outreach and/or program modifications may be needed to expand benefits to additional groups.

Comments