So, how many people really use foodbanks? The emergence of foodbanks – charitable organizations that provide emergency food for those in need – represents a shocking manifestation of severe poverty and food insecurity in contemporary Britain. In the absence of more direct information, foodbank use is commonly taken to represent extreme levels of uncertainty in obtaining sufficient, suitable food.

When people visit foodbanks more than once, they are also counted more than once, so the true prevalence of foodbank use in Britain is unknown.

Despite highly publicized growth, the scale of foodbank use has been subject to heated debate. Food insecurity is associated with poor mental and physical health, and disabilities, so the recent growth in foodbank use could warn of an escalating nutrition and public health crisis in Britain.

This work aimed to address a key evidence gap in estimating the scale of foodbank use. The Trussell Trust – Britain’s largest foodbank network – collects headline data on the number of food parcels given to adults and children. However, when people visit foodbanks more than once, they are also counted more than once, so the true prevalence of foodbank use in Britain is unknown.

In this project, each household’s annual number of visits was estimated by cross-referencing the names and addresses of people receiving emergency food from West Cheshire Foodbank. This approach made it possible to identify the unique number of households receiving assistance. This work therefore presents the first attempt to estimate the scale of UK foodbank use among adults and children.

I found that an estimated one per cent of the population of West Cheshire received emergency food between 2013 and 2015. Worryingly, this figure was higher among children. If scaled up, this would equate to approximately 850,000 people in Britain – nearly the population of Liverpool – who rely on emergency food to feed themselves and their families. This proportion rose slightly over time, consistent with national trends.

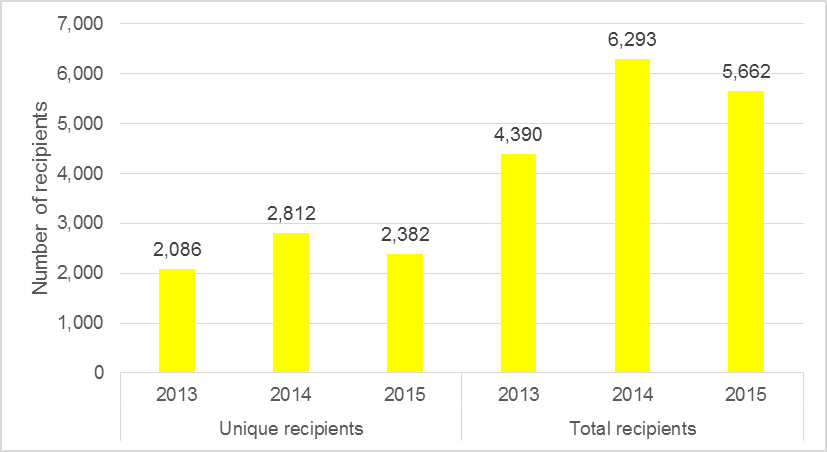

Detailed analyses revealed that the growth in repeat visits outpaced the increase in total visits (see Figure 1), suggesting that foodbank use is becoming more entrenched among certain groups. Repeat visits were more common among working-age and one-person households, groups who have been particularly badly impacted by the recent recession and consequent welfare reform. This finding replicates existing research on the topic and strengthens the evidence linking economic and social policies to foodbank use.

If scaled up, this would equate to approximately 850,000 people in Britain – nearly the population of Liverpool – who rely on emergency food to feed themselves and their families.

Of course, these results do have some limitations. First, they relate to a single foodbank, which cannot fully represent Britain’s diverse population. Nonetheless, these results are consistent with what is known nationally.

Taking a localized approach also enabled unique households to be identified, a time-consuming task. The next step to a more complete impression of UK foodbank use would require the same strategy to be repeated among a carefully selected sample of foodbanks – a daunting undertaking that may not be practically possible. This approach would still under-estimate the number of people using foodbanks as independent foodbanks would not be included.

It is also important to remember that foodbanks are commonly considered a ‘last resort’ and used by only a small minority of food insecure people, often because people feel embarrassed or ashamed. Separate estimates that between 10 and 20 per cent of people in Britain experience food insecurity demonstrate that foodbank figures drastically underestimate the scale of the issue.

This new work adds to growing evidence about foodbank use in the UK. Practitioners are increasingly well versed in the problem of food insecurity, and may have seen its effects first-hand: one in six of GPs reported having been asked to refer patients to foodbanks in 2014. The health consequences of food insecurity are costly to the public purse. Wide-reaching measures to reduce food insecurity are crucially needed and should especially target the particularly vulnerable groups identified here.

Comments