Over half the world’s population today resides in cities, creating a challenge for urban planners to efficiently accommodate increasing numbers of residents in a healthy and positive environment.

Mental health in particular is important, with statistics showing that one in four of us experience mental health difficulties each year, while those with better, positive mental wellbeing display increased levels of longevity, productivity, and prosperity. In fact, the UK government now measures mental wellbeing, alongside traditional GDP, as an indicator of national progress.

Biophilia

Previous research found those in greener urban environments reported fewer symptoms of mental distress and better life satisfaction.

The theory of Biophilia suggests that individuals have an innate desire to connect with nature, due to the savannah landscapes humans evolved in, and are hence best adapted to. People may therefore still experience positive emotions in more natural environments.

Previous research has suggested this to be true in a modern context, where those in greener urban environments reported fewer symptoms of mental distress and better life satisfaction. In particular, these symptoms have been shown to reduce for individuals relocating to greener areas.

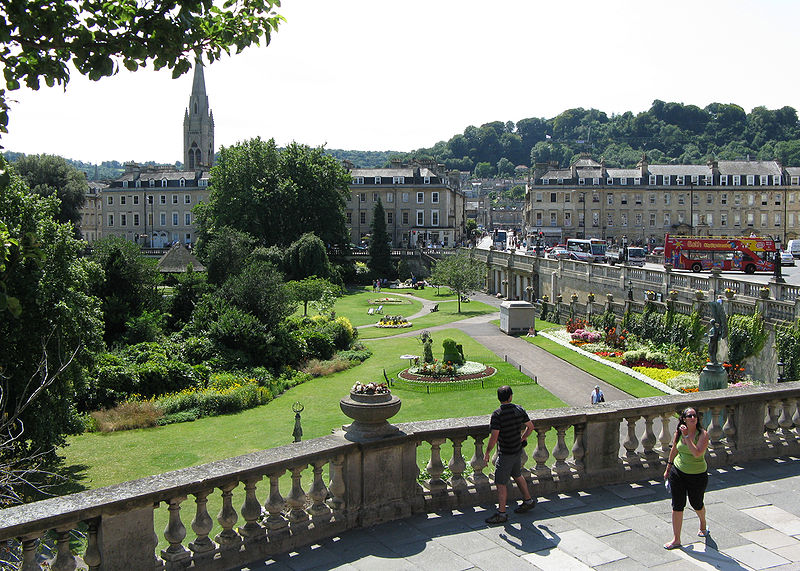

It is therefore important that green spaces are designed into urban areas to provide places for individuals to connect with nature. These spaces may also offer opportunities to pursue other health-promoting behaviours such as exercising, active travel, preserving wildlife, and socialising, which can help foster a supportive network.

Mental wellbeing

However, little research has focused on mental wellbeing, a concept which comprises positive aspects of mental health, such as happiness, functioning and purpose in life. Our study set out to examine whether local-area proportions of green space would be associated with this broader definition of mental wellbeing, measured using the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS). This questionnaire consists of 7 questions, asking respondents how they have been feeling over the past 2 weeks, covering aspects such as optimistic about the future, relaxed and useful.

Initial results showed that green space was positively associated with the mental wellbeing measure, but after controlling for a range of personal and environmental factors, we found that individual lifestyle factors and local-area deprivation were significant predictors of mental wellbeing, while green space was not.

While this was not the finding we expected, it opens up many other questions regarding the relationship between green space and mental wellbeing. It could be that defining local-area green space as the amount within a census boundary is too coarse a measure, as in this project, and that taking account of how far people have to travel to visit their nearest green space, may yield more positive results.

Green space itself is also much more complex than a single entity, and may take the form of a nature reserve, park, sports pitch, cemetery, allotment, or many others. We speculate that the features of these different places may be beneficial in themselves, and we have begun pursuing investigations into the associations between these different green characteristics and mental wellbeing.

We found that individual lifestyle factors and local-area deprivation were significant predictors of mental wellbeing, while green space was not.

It may also be that potential benefits depend on the individuals themselves. For example, older people may prefer green spaces with benches and toilets available, whilst young families may find play equipment and open spaces preferable. Those who commute may have more opportunity to benefit from green space nearer their workplace than home, or areas traversed while commuting, as this is where they spend most of their time during the week.

This leads on to the concept of exposure: while studies do not agree whether having greater amounts of local green space is associated with usage, examination of visiting patterns and activity types may also be an interesting area of further research.

What is clear, however, is that future studies need to examine different green space characteristics in association with this broader definition of mental wellbeing, in order to understand if, and where, these relationships exist.

Longitudinal studies will also allow potential consideration of causality. Our future research will focus on a spatial modelling approach to expand our understanding of accessibility and the importance of these different green space types.

With urban growth currently increasing at an unprecedented rate, there is rising pressure on city planners to ensure that limited space is put to its optimum use. Green spaces are only present in urban areas at the expense of buildings, and as such it is important that they are designed well to offer to greater benefit to the widest population.

Informed green space design will help create a healthier, happier and more productive urban landscape, while there may be wider benefits still for the environment and the economy.

Comments