The evolutionary history of lions is opaque, as most of the sub-species that once roamed the Old World are now extinct. However new research, published in BMC Evolutionary Biology, uses ancient DNA from extinct lions to piece together the gaps in their history. The findings provide both a new understanding of the lion’s past and may provide new insight into how to conserve what remain for the future.

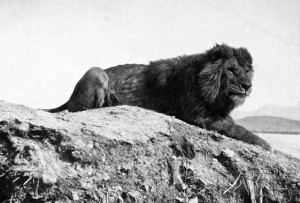

Lions once roamed across the world. Until relatively recently, various sub-species could be found across Africa and all the way from the Indian subcontinent, through the Middle East and into modern day Greece and Turkey. Visitors to the British Museum in London can see engravings from Assyria (in modern day Iraq) made as recently as 635BC of large scale lion hunting by the local people (see picture). Sadly these hunts, and others like them, were rather too successful. Along with increasing human encroachment on their habitats, persecution has resulted in the virtual extinction of lions outside of sub-Saharan Africa. The Asian lion lives on only through a small and highly endangered Indian population of approximately 400 individuals; all other lions outside of sub-Saharan Africa are extinct.

These recent extinctions create problems for our understanding of the evolutionary history of lions. Such an understanding is desirable not just to satisfy our curiosity about these charismatic animals, but also to help focus efforts for conserving those lions that still remain. Yet sampling only those lion populations that are still in existence inevitably gives an incomplete – and perhaps misleading – impression of this species history.

Well then, suggests new research recently published in BMC Evolutionary Biology, why not use what remains of extinct lions to fill the gaps in their history?

Origins of the ancients

A worldwide team of researchers, led by Ross Barnett of Durham University, searched museums across Europe to locate bone or tissue specimens from extinct lions, in order to extract their DNA. Samples from extinct lions originally living in West, Central and North Africa, as well as some from the Middle East, were tracked down, of which a number had somewhat unusual origins. Two skull fragments from North African Barbary lions, now housed in London’s Natural History Museum, were originally found underneath the Tower of London during building work, presumably remnants of the Tower’s medieval Royal menagerie.

Extracting mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from these museum samples and combining the DNA with 74 previously published mtDNA sequences from existing lion populations in Africa and Asia enabled the authors to estimate both the relatedness of these different populations (ancient and modern) as well as the likely dates they separated from one another.

Consistent with previous analyses, the researchers find that the most likely origin of lions is eastern-southern Africa. What’s new is the estimated date for the migration of lions out of Africa and into Asia.

Previous research, based only on existing populations, suggested that this occurred at least 74,000 years ago and perhaps as long as 500,000 years ago. This new work suggests that the exodus of lions out of Africa occurred a mere 21,000 years ago. The additional use of ancient DNA from extinct populations has then resulted in substantially different conclusions from studies using living lions only.

Out of Africa

This data also allows the likely course of this migration to be mapped. The results suggest that, having initially arisen in East Africa, lions migrated to West and Central Africa approximately 120,000 years ago; climatic change then separated these two populations.

The authors analysis suggests these western populations were the pioneers who migrated into North Africa and from there into Asia, Europe and the Middle East (see figure 3 for more details). Genetically then, modern day lion populations in West and Central Africa appear to be more closely related to existing Asian Lions (and all those now extinct populations in-between) than they are to East African lions.

Given that these West and Central African lion populations are close to extinction in the wild, this has potentially important implications for lion conservation. Currently, all African lions are considered to represent just one conservation unit, with Asian lions making up a second. The authors strongly suggest that this dichotomy now needs to be revised. Central and West African lions are actually more closely related to Asian lions and, to preserve as much lion diversity as possible, extra attention needs to be given to these populations. This research then, does not just change our perceptions of the lion’s past but may also change our perception of how to safeguard its future as well.

Ancient DNA comes of age

These results come with caveats. All these findings are based on maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA which, as the researchers readily admit, cannot be considered as accurate as phylogenetic analyses based on biparentally inherited nuclear DNA. This is a particular concern in species like lions, where it is males that migrate between populations, while females usually remain with the group of their mother.

Of course the reason for using mtDNA is that it is easier to extract successfully from difficult samples like bone fragments than nuclear DNA. Perhaps in the future next generation sequencing techniques will enable the extraction of nuclear DNA from such samples with sufficient quality to confirm the authors results. Even without this confirmation, it remains extraordinary that we can reach back into the past and utilise the DNA of animals dead many centuries, whose entire sub-species are no longer found anywhere on earth. Ancient DNA studies have the potential to explain the diversity of the past and, perhaps, help us conserve it for the future.

Comments