The charmingly named bushbabies (or galagos, from the family name Galagidae) are famously large-eyed nocturnal primates, native to continental Africa. An intriguing family, the Galagidae contains one of the smallest living primates, Galagoides rondoensis, weighing in at ~60g but it is also home to some species that can grow as large as a domestic cat. Galagos are capable jumpers, feeding on a range of foods as diverse as insects and gum and are known to live in a variety of different social hierarchies. Yet their nocturnal habits and often remote habitats mean that they are the least well-studied of all the primates and still relatively little is known of the biology of this enigmatic species.

The species diversity and evolutionary relationships of bushbabies remain a contentious question in primatology, complicated by their being among the most morphologically cryptic species of all primates. This has recently led to a number of new species being described based on advertisement (mating) calls, which are suggested to play a role in reproductive isolation and is a common identification technique in taxonomic studies of primates. This has been particularly true for the dwarf galagos, whose numbers have swelled from five to twenty species in recent times. Yet the validity of this genus is still uncertain and indeed there is a general lack of consensus regarding the phylogenetic history of galagids as a whole; particularly with regard to the interrelationships of the genera, their relationship with lorises and the history of the early divergences within the family.

Understanding the cryptic diversity among the galagos has the potential to prove useful in designing conservation directives, and in their recently published BMC Evolutionary Biology paper, a team led by Luca Pozzi of New York University looked to new molecular data in an effort to unravel the phylogenetic history of the bushbabies and their nearest relatives the lorises. Their dataset, sampling 27 different genes from a selection of museum specimens, reference samples and animals captured in the wild, represents the largest molecular dataset of galagids to date.

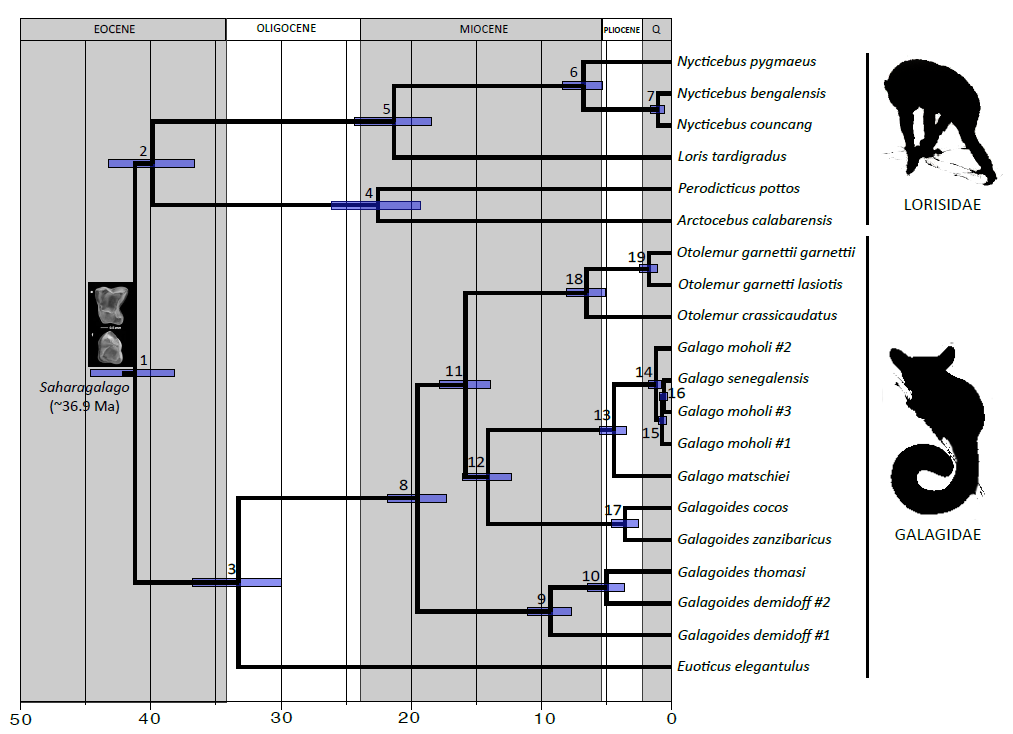

This ambitious study succeeds in shedding light on several contentious aspects of galagid relationships. It provides strong support for a basal position of the needle-clawed bushbabies (genus Euoticus) within the Galigidae, a relationship that has likely been concealed by long branch attraction and/or inaccurate identifications of specimens in museum collections – both common problems in phylogenetic reconstructions of ancient relationships of elusive creatures. According to the age estimates calculated in this study, Euoticus represents one of the oldest lineages of extant Primates and its divergence during the Early Oligocene (33.9 million to 23 million years ago) is independent of the radiation that gave rise to all the other main galagid lineages later in the Miocene (as detailed in the chronogram below).

Another finding of the study lends further weight to recent molecular analyses in recovering a non-monophyletic Galagoides with two distinct clades; a western clade and an eastern clade. This is in contrast to the monophyletic grouping that has traditionally been supported by morphological studies and which is often now referred to as a “wastebasket taxon of plesiomorphic species” i.e. based on an ancestral trait and not taking into account recent divergences. Based on their findings, the authors suggest a new genus for the Zanzibar galagos and a re-arrangement of current taxonomic groupings to match.

Yet, the interrelationships between the Zanzibar galagos, greater galagos and lesser galagos still remain unresolved to a degree, as does the relationship between the galagos and the lorises, with short branches complicating phylogenetic examination of molecular data. Similar to other molecular studies of its kind, this study, despite the large number of loci and comprehensive taxonomic sampling, fails to resolve the relationships between the galagids, Asian lorises and African lorises with any reliability. The various hypothesized relationships among the bushbabies and lorises (and the differing extents to which they are supported by molecular and morphological data as discussed in the paper) provide an insight into the complex evolutionary history of the bushbabies and lorises, and while it may not quite provide all the answers, this paper could well represent a milestone in galagos phylogenetics, introducing a new classification and providing a valuable resource for future studies.

Comments