BMC Ecology reflects on the first day of INTECOL 2013, a conference which celebrates more than 100 years of ecological research

Twelve months ago, London’s Excel Centre was host to boxers, wrestlers and martial artists battling it out for Olympic glory. One year on, and with tongue firmly planted in cheek, President of the British Ecological Society Georgina Mace surveyed an assembled crowd of 2000 ecologist representing 67 different countries and concluded: “not much has changed”.

Like the Olympics, INTECOL is a gathering that happens every four years. Unlike previous meetings, this year it has a guest: The British Ecological Society (BES) celebrates 100 years since its inception by Sir Arthur Tansley. He who would no doubt have been amazed by the breadth and diversity of symposia on offer at this years joint meeting, speculated Illka Hanski at a celebratory opening ceremony.

Like the Olympics, INTECOL is a gathering that happens every four years. Unlike previous meetings, this year it has a guest: The British Ecological Society (BES) celebrates 100 years since its inception by Sir Arthur Tansley. He who would no doubt have been amazed by the breadth and diversity of symposia on offer at this years joint meeting, speculated Illka Hanski at a celebratory opening ceremony.

The first plenary of the day saw Sandra Diaz of Córdoba National University in Argentina guide us through a historical tour of plant functional traits that took in 4th Century Greek philosopher Theophrastus —the father of functional ecology who first classified plants into different functional forms —and on to Charles Darwin and his famous description of the complexity of form and function in the “entangled bank” of life. The present day and the power of data sharing followed, with a demonstration of the TRY database. This huge integration of datasets on functional traits facilitated a massive analysis of 43,000 plants covering 430 taxonomic families, though currently still hosts a proportion of data under restricted access.

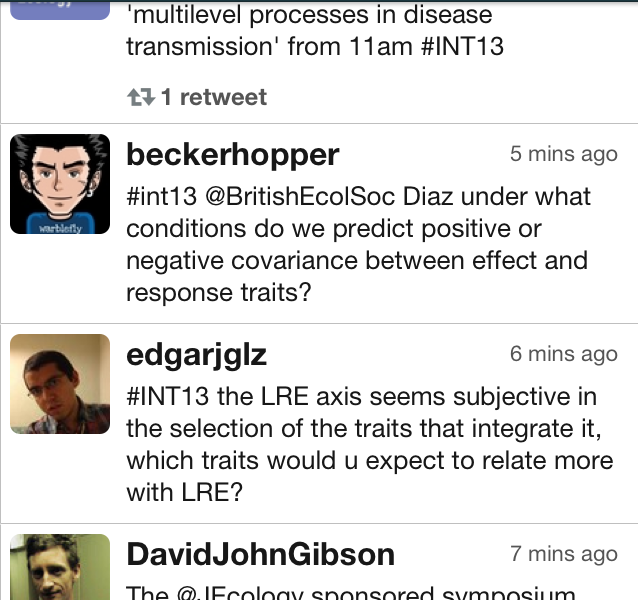

An unusual foray into the digital present also greeted plenary question time, with all questions being collated via Twitter before being put to the speaker. “Some people are looking forward to it more than others” noted Georgina Mace, anticipating some good-natured dissent. Fortunately, BES helpers were on hand with social media tutorials for the uninitiated.

An unusual foray into the digital present also greeted plenary question time, with all questions being collated via Twitter before being put to the speaker. “Some people are looking forward to it more than others” noted Georgina Mace, anticipating some good-natured dissent. Fortunately, BES helpers were on hand with social media tutorials for the uninitiated.

Mentions of Charles Darwin are of course never far from an ecological conference, but speaking in the first of the morning sessions, Ben Holt of the University East Anglia (UEA) gave a fascinating update to the work of Alfred Russell Wallace (“not Darwin, the other one”), who this year also celebrates a centenary of sorts, with 100 years since his death. Re-analyzing the zoogeographic regions outlined in Wallace’s “Sarawak law” paper to include previously overlooked groups like amphibians, they find a few fascinating biogeographic discrepancies compared to the original study —including a surprising lack of evidence supporting the famous “Wallace line”.

Following directly on from this, Chris Thomas (University of York) raised the rather controversial possibility that perhaps humans haven’t had such bad effect on species diversity as we often assume, questioning the assumption that climatic change is likely to reduce regional species diversity. Citing the UK as an example of a country where human-induced change appears to have counterintuitively increased overall species diversity relative to the number of regional extinctions, he made a compelling case for not overlooking these cases as unusual exceptions.

The finger of blame could not be pointed toward climate change when it came to mega-herbivore extinctions some 40,000 years ago, an analysis of ancient dung fungi from New Zealand suggested. Chris Johnson’s engaging talk dug deep into the Pleistocene to a resolution of 100 years (!) to look at patterns of vegetation change, whilst more contemporary fecal foraging was the order of the day in Stéphane Boyer’s description of molecular methods for diet analysis in currently endangered species.

Just before hitting the floor and exploring the poster sessions, there was also time to catch Audrey Zannese of UEA describe a study comparing butterfly species’ dispersal responses depending on whether they are currently undergoing a shift in their distributional range. This elegant translocation experiment seemed to touch on the best of both classic and contemporary ecology, combining good old-fashioned butterfly chasing with high-tech GPS tracking to map at very fine scales how individual butterflies respond to release in a novel location. It’s a design that i’m sure Tansley and Wallace would both have been fascinated by.

Go on then, Darwin as well.

Comments