Imagine a woman who has just had her regular mammogram and learned that there is a suspicious mass in her breast. In order to find out if the mass is benign or malignant, the next step would be to take a biopsy and have it analyzed by a pathology specialist.

Unfortunately, even in the United States and Europe where there is relatively easy access to breast clinics and specialized physicians, it can often take days or weeks to receive the biopsy results. And in some cases, the results from the first biopsy may be inconclusive and another biopsy is needed, further delaying surgery and treatment.

During this period of waiting, the woman can do nothing but ponder numerous uncertainties all revolving around one question: “Do I have breast cancer?”

Now consider a woman in a country with limited economic resources, like Tanzania, where there are only 15 pathologists in the entire country, or 1 pathologist per 2.5 million people. In comparison, the United States has over 18,000 pathologists, or 1 pathologist per 17,500 people.

For this woman, it can take weeks to months to receive a diagnosis. In such cases, many patients are unable to return to receive their test results. Consequently, many women in low resource settings do not receive the treatment that they urgently need.

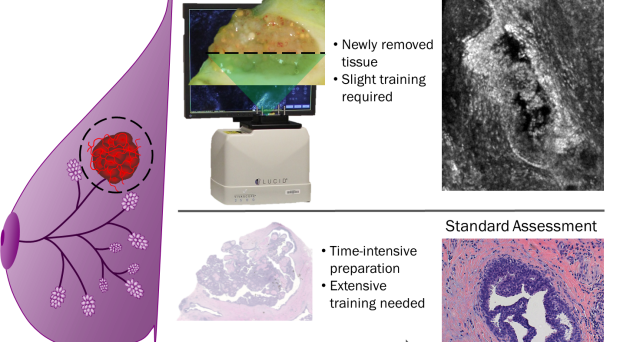

The standard procedure to diagnose breast cancer is through acquiring a biopsy of a suspicious mass. The biopsy is then fixed in formalin to prevent decay of the tissue, cut into thin sections, mounted onto a glass slide, and stained to visualize architectural details.

A pathologist then examines the slide under a microscope and gives a diagnosis. This process of tissue preparation and diagnosis requires many consumable supplies and expertise.

Thus, there is a vital need for tools to rapidly evaluate breast masses and classify them as benign or malignant. Ideally these tools would require few consumables and minimal training to make an assessment.

A few years ago, our research team decided to address this need by developing a method that would classify breast tissue based on quantifiable characteristics.

Over a period of three years, we received breast tissue from patients with breast cancer. To image the specimens I used a confocal microscope that can resolve structures smaller than the size of a breast cell and can acquire images in only a few minutes without extensive preparation.

Initially, Jenna Mueller and I were working on two separate projects. My research was focused on evaluating breast ducts, where approximately 80% of breast cancer cases develop. Jenna’s work was focused on evaluating several characteristics of benign and malignant breast cell nuclei.

When Jenna and I integrated our evaluation methods and used properties related to both breast cell nuclei and breast ducts for automated classification, we found that we could categorize a wide range of benign and malignant breast tissue types.

By combining parameters that described the arrangement of cell nuclei and the amount of cellular material within a breast duct, we could quantitatively distinguish between a variety of benign and malignant masses with high accuracy.

Researchers such as Ozaki et al. and Anderson et al. have shown in earlier studies that it is possible to use computerized methods to evaluate characteristics of breast cells and ducts in order to classify tissue as benign or malignant. However, these studies used thin sections of fixed tissue, which require extensive time and resources in order to prepare for imaging.

In our study, we took the idea of using computerized methods on fixed tissue one step further by applying it directly to tissue, which can eliminate the need for extensive and costly tissue preparation. This could enable automated and rapid diagnosis of tissue at the point of care.

While pathology will continue to be the clinical standard for diagnosing cancer, new technologies have the potential to significantly decrease the delays in receiving a preliminary diagnosis from weeks or months to a few hours or even a few minutes.

This new technology could potentially enable a woman to learn her diagnosis on the same day as her biopsy and either prepare for treatment or go home confident that she is healthy.

Comments