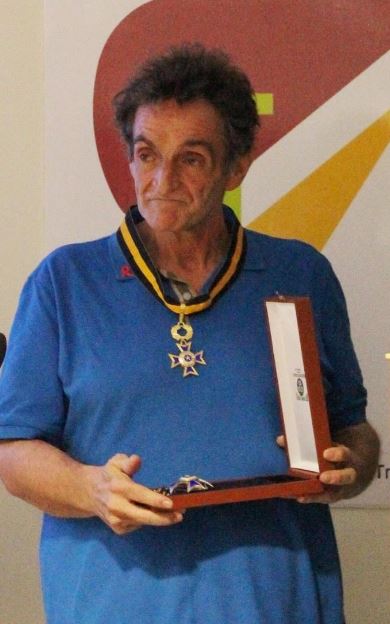

Second in this series is Luis Mendão, chair of both the European AIDS Treatment Group (EATG) and Group of Activists on Treatments (GAT), a treatment activist group in Portugal.

You’ve worked with hepatitis C for many years now. How has your focus changed?

I was diagnosed with HIV and HCV in ’96, but I started working in the field of drug-policy reform in the mid-eighties in Italy and Portugal. HCV was of course epidemic among people who injected drugs. My diagnoses were very late, yet I managed to get access to one of the new triple combinations for HIV.

After 2000, I tried hepatitis treatment, but the side-effects were a nightmare. So I started GAT in Portugal, a group advocating for coinfected people to push for safer and more easily tolerated drugs under the EATG.

We advocated for first access to new drugs for everyone, and we campaigned for elimination by pressuring the industry to drop prices. We haven’t been very successful in most places, but in my native country of Portugal, we finally got the government to commit to treating everyone in the health system who’s known to be infected. We expect to achieve this by February 2017.

As part of EATG, I helped form the HCV Community Advisory Board in 2009, a group of North American and European treatment activists who met with drug companies on behalf of the infected community. An excellent collaboration between organizations that usually don’t work together.

Did you ever get treated?

With the new drugs, I refused treatment for some time because there was no access in Portugal. But when the agreement was finally reached, I obtained access to the AbbVie regime under compassionate use.

And they’ve declared me cured. It’s only been five months, yet the brain’s a bit clearer, the pruritus is better, and I seem a little less tired. We’ll see.

What major challenges lie ahead for the field of hepatitis C?

The task now is not just prevention, but identifying people who don’t realize they’re infected and connecting them to care.

The task now is not just prevention, but identifying people who don’t realize they’re infected and connecting them to care. The challenge we’re focusing on is reaching people who use drugs and people who are in prison, where treatment rates are very low.

Transmission is also high among men who have sex with men, especially those with HIV. The European Commission has been backing out of its mandate, so we’re lobbying them for an elimination strategy that includes access to prevention, diagnostics and treatment.

What areas of hepatitis C research are being neglected?

First, we need affordable point-of-care diagnostic tools that will detect the virus and not just antibodies. Second, for hard-to-reach populations, we need a cure in the form of a single long-acting injection (say 2 – 3 months).

And finally, we need better medical tools to treat liver damage caused by hepatitis C. Too many people who’ve been cured are still dying early due to liver failure, decompensation and cancer.

Two presentations by Luis

- “Access to hepatitis C treatment in Europe and abroad: the question of pricing and the view of people living with hepatitis C”

- Harm reduction/drug policies for PUD and hepatitis C elimination” (start 2:25:28)

The EATG website

The ELPA website

Hepatology, Medicine and Policy has launched with BioMed Central. For more information, visit: www.hmap.biomedcentral.com.

Comments