A study published at the end of July in International Journal of Health Geographics suggests that changes in the built environment can increase how far a person will walk to get somewhere. So why should we be bothered about getting people walking?

Walking is a big part of my life. Not only do I love getting out to the countryside for a good old ramble, I walk as much as I can in the city (which, for me, is usually London). This wasn’t always the case. A few years ago, it wouldn’t have occurred to me to walk to work, for example. I just opted for the quickest journey time – bus, tube, whichever was faster.

That all changed when I signed up to take part in a charity walking event and decided to train for it by walking to and from work (about three miles each way). It was then that I realized walking is severely underrated as a form of exercise. Since I started walking to work, which was about three years ago now, I’ve gone from doing virtually no exercise to becoming not only a walker, but a runner too. Oh yes, and I lost four stone (56lbs/25.5kg) along the way!

Surprisingly enough I’m now quite the walking evangelist. I’d like it if everyone could be persuaded to make walking their transport mode of choice. However, it’s not always straightforward for people to just step out of the door and walk to the shops, or the office, or to see their friends. The environment they have to walk in may well influence how they feel about taking a stroll down the street.

Since I’ve been walking around London, I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s built pretty well for pedestrians, particularly if you get to know the quieter back roads where you can avoid the traffic. But a lot of people don’t know these routes. Or perhaps they might live in a less walk-friendly city. Or perhaps in a village with very few pavements (sidewalks).

So how much does someone’s environment influence whether they’ll walk? I’m sure you can imagine my interest when I spotted a recent article in International Journal of Health Geographics (IJHG) which has measured the impact that the built environment can have on people’s walking behavior.

This isn’t a new subject, as this paper by James Sallis and colleagues, dating back to 10 years ago shows. In fact, it’s something that’s become an increasing focus for urban planners and health practitioners who want to encourage healthier lifestyles. Walking is recognized in the UK as exercise that contributes towards the recommended amount of physical activity that everyone should be doing a week (150 minutes in case you were wondering). So it’s worth our while to be providing spaces where people can get walking.

This latest article in IJHG discusses some of the challenges of measuring the impact of the built environment on walking, with ‘confounding factors’ playing a big part in producing mixed results. On such, is residential self-selection, where it can be difficult to determine if a person has chosen to live in an environment conducive to their preferred modes of transport, or if the environment they live in has influenced their preferences.

For their study, the authors took advantage of the fact that a known change in the built environment had been planned. This gave them the opportunity to carry out a longitudinal study to examine what impact this would have on the walking behaviors within the Chinese University of Hong Kong campus.

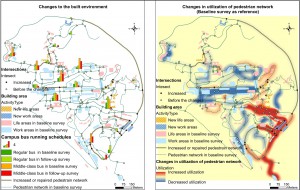

This change aimed to accommodate a predicted increase in enrollment. Both this “steeply contoured” university site, as well as its transportation schedule were being adjusted, and pedestrian networks were to be increased or repaired.

The researchers recruited subjects from amongst the students who had been using the campus before the changes to the environment took place. They conducted surveys both before and after the changes, as well as asking subjects to keep a walking diary. At the same time they also mapped various built environment variables, such as the number of intersections and, therefore, the ‘connectivity’ of the pedestrian network.

Their findings back other studies that show that a better ‘connectivity’ of the pedestrian network does increase the amount of walking people do. To me, this seems a pretty obvious and common sense result. But in order to influence policies, clear evidence is needed. It’s not enough to point to anecdotes and common sense when large amounts of possibly-public money could be at stake.

Studies like this one add weight to the argument that we should be making it easier, and hopefully more pleasant, for people to walk from A to B.

Comments